- Share via

MINNEAPOLIS — Jamar Nelson was asleep on his couch more than two decades ago when police burst into his apartment, beating him and leaving a gash in his head that required 13 stitches. Every time he touches the scar, he is reminded of what happens to many Black men whose lives collide with law enforcement.

“I’ve seen plenty of police brutality,” Nelson said, recalling that day when police raided his duplex for drugs. He was not arrested or charged. “The harassment, the profiling, the intimidation.”

But last summer as politicians and activists discussed abolishing the Minneapolis Police Department after George Floyd died beneath the knee of Officer Derek Chauvin, Nelson looked out over a city not only traumatized by police but by a surge of violent crime that was sweeping a nation that in 2020 recorded the largest percentage increase in homicides in a single year.

Getting rid of police suddenly felt like the wrong goal, said Nelson, a community activist. Homicides, rapes, robberies and assaults jumped about 25% in Minneapolis from the previous year. The city’s 82 homicides in 2020 were double the four-year annual average.

“A community has to have some form of policing,” he said, stressing that more focus should be placed on hiring officers who understand and empathize with the neighborhoods they patrol. “We need police, police who live in the community — Black communities — and who are from the community.”

As testimony in Chauvin’s murder trial enters its third week, Minneapolis has, once again, found itself at the forefront of a debate seared with a legacy of racial injustice: What is the future of policing in America, and what’s the best way to get there?

Almost everyone here agrees that policing needs to change — it’s impossible to watch the video of Floyd’s final breath and think otherwise, they say — but they’re split on how that should happen, especially in the aftermath of nationwide demonstrations that demanded departments reform even as they angered many police officers who felt unfairly vilified.

Is the answer less taxpayer money and fewer officers on the streets? Or would more officers — people with ties to the communities they patrol — improve things? Many people here believe that investing more money in schools and community programs is key, but should that money be diverted away from patrol budgets?

The Chauvin trial — with its medical experts and tearful witnesses — is unfolding against this debate as if a real-time morality play on the consequences of bad policing. Whether jurors ultimately decide to convict Chauvin, who faces murder and manslaughter charges, will no doubt shape views on how to reform law enforcement in an age of viral videos and Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

“This trial and its outcome is a pivotal event for understanding the soul of America,” said Delores Jones-Brown, a visiting professor at Howard University and a professor emeritus at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “Moving ahead, what we’re seeing is a debate over reallocation and reduction in funds for policing in the country.”

Such conversations in the weeks after Floyd’s killing have already spurred action in some cities.

In July, the Los Angeles City Council approved a $150-million cut to the police budget, a move local politicians said would translate into more money for services to help disenfranchised communities. Cities in the Pacific Northwest considered alternatives like calling mental health experts and not police to certain scenes. But perhaps in no place are these questions more resonant than in Minneapolis, where Floyd’s death sparked protests around the globe.

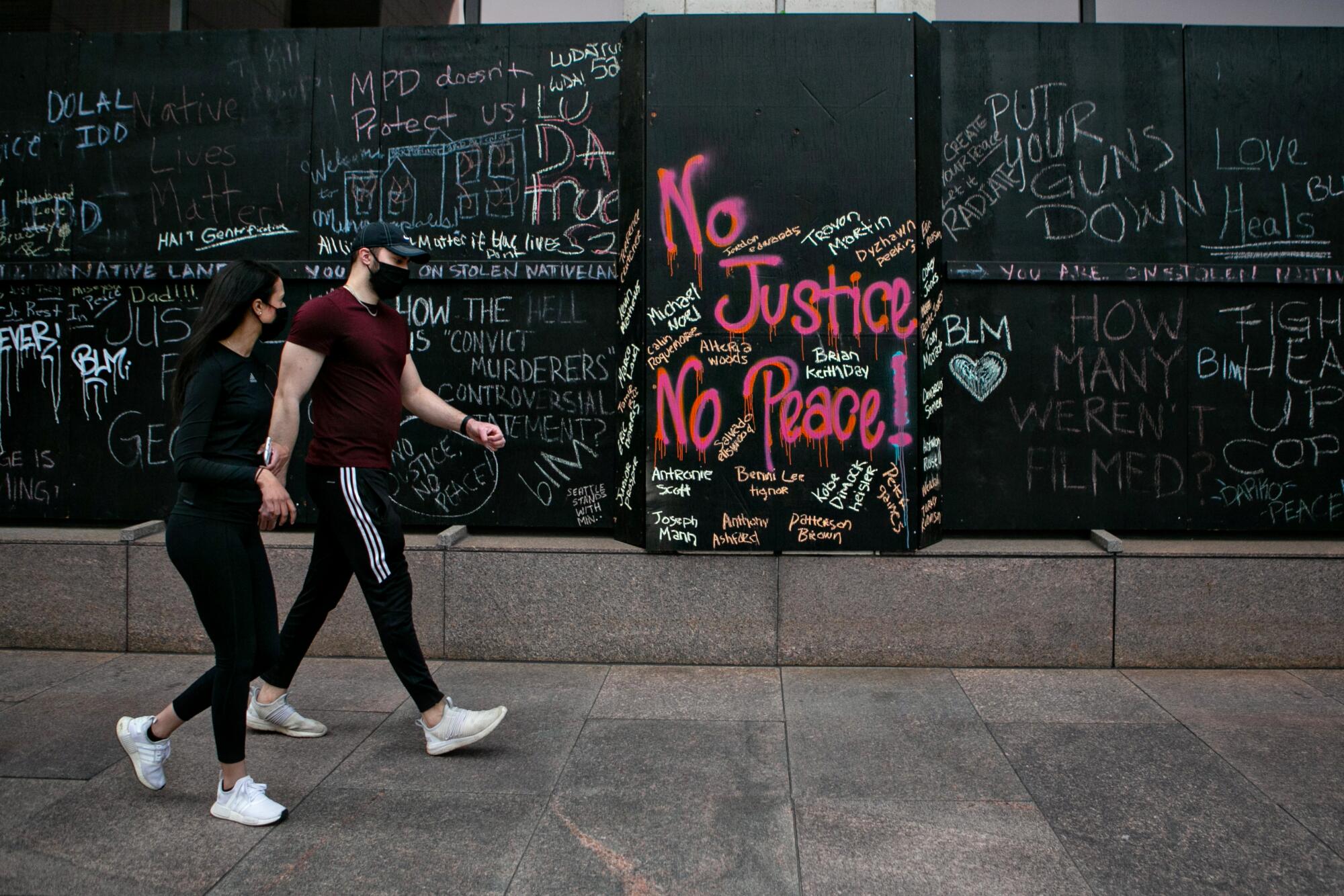

In June, a majority of the Minneapolis City Council pledged to dismantle the Police Department while standing in a South Minneapolis park adorned with two massive words: “Defund Police.” But in the weeks that followed some residents criticized the plan, arguing that it felt deeply out of sync with their lived realities, especially as the region experienced an increase in violent crime.

“It’s been wild out here,” Nelson said of the rising crime in his predominantly Black north side of Minneapolis, whose high poverty rates have been shaped by decades of neglected school funding and racist redlining. “And then people hear rumors about the police going to be abolished and it’s basically everyone for themselves,” he said.

After Floyd’s death on May 25, the size of the city’s police force shrunk drastically.

Since 2020, the department’s force of nearly 870 officers has fallen to about 630. Roughly 150 officers are listed on some form of extended leave due to post-traumatic stress disorder, according to department statistics. In some cities, including Minneapolis, crime rose as unemployment soared during the pandemic and as police were preoccupied with protests or appeared less vigilant as public anger intensified against them.

The City Council ultimately walked back its all-out pledge to abolish the department. But in December the council voted to divert nearly $8 million of the department’s $180-million budget to community-based approaches to policing. Last month, the council advanced a measure that could go before voters this fall calling for the city to create a new Department of Public Safety that would encompass a broader health and social approach to fighting crime.

“The vote was an acknowledgment of the need to fundamentally change a system that serves white people better than it serves people of color, and that disproportionately exposes some in our city to harm,” Council Member Steve Fletcher, a sponsor, said at a virtual meeting when it passed.

A similar ballot measure that could go before voters —an effort spearheaded by a coalition of liberal groups and young activists, which gained momentum after Floyd’s death — would also replace the Police Department with a newly created Department of Public Safety.

Approving such a department, supporters of the Yes 4 Minneapolis measure say, is the best way ensure safety that prioritizes public health. Radical change is necessary, they say, when faced with a department that has paid out millions of dollars in settlements in police brutality cases.

The city recently announced it would pay Floyd’s family $27 million in a settlement.

“For decades, MPD has killed, profiled and over-policed Minneapolis community members — especially Black and Native people — while also failing to solve issues like gun violence, intimate partner violence and addiction,” said Corenia Smith, campaign manager for the measure. “The MPD has had more than 150 years to address our most urgent problems. It’s time for the community to take the lead in what we want.”

Some other Minneapolis residents, however, believe the answer lies not in getting rid of the department but in reimagining it so it is no longer scorned after decades of mistrust.

After Floyd’s death, Minneapolis Chief Medaria Arradondo, the city’s first Black police chief, and Mayor Jacob Frey pushed for widespread policy changes, including bans on police chokeholds or neck restraints and a requirement that officers intervene if a colleague uses improper force. Arradondo’s trial testimony last week against Chauvin’s actions was a telling sign that police may be more inclined to break the so-called blue wall of silence in protecting fellow officers.

Working with the department on necessary reforms is the best solution, said Gwen DeGroff-Gunter, who retired from the Minneapolis Police Department in 2012.

“It’s ridiculous to say ‘abolish,’ even ‘defund’ the police,” said DeGroff-Gunter. “Reform, sure. But it makes no sense to ever go down that path as the city sees an increase in violent crime.”

DeGroff-Gunter, who is Black, said that, in the days after Floyd’s death, she reached out to the half a dozen or so Black female police officers on the force, who told her they felt numb after watching the viral video.

“It’s also what I felt,” she said. “I still feel numb. … In policing, there has to be a level of empathy and humanity. There was none of that for George Floyd.”

Today, if you walk around the intersection of 38th Street and Chicago Avenue, outside Cup Foods — where, less than a year ago, Floyd screamed out that he could not breathe as Chauvin pinned him to the ground for 9 minutes and 29 seconds — police officers are a rare sight. They’ve limited patrolling the area as people visit and mourn Floyd.

Keeya Allen, who works at a neighborhood association a few blocks from where Floyd died, has spent time at Cup Foods and knows officers from the 3rd Precinct, where Chauvin worked.

She has followed the first two weeks of the trial closely and said she was pleased to see Arradando speak out against Chauvin, criticizing his actions as excessive.

“There needs to be police, there needs to be good police,” she emphasized. “I’m not sure what you get from doing away with policing altogether. More crime?”

In the last year, Brandon Porter, who lives three blocks from Cup Foods, said he’s at times heard gunshots — something he didn’t hear in years past: “It’s common sense you need police officers,” said Porter, who noted that some of his neighbors had their windows shattered by bullets.

A few blocks away, Earnestine Milton, 72, has similar fears.

“If you defund or don’t have police, what are we supposed to do?” said Milton, a retired judicial assistant, who, like Porter, is Black and has lived in the same house for 42 years.

“It was nice,” Milton said, emphasizing the past tense, “a peaceful neighborhood.”

But someone recently broke into her garage and stole her grandchildren’s bikes, she said, and a neighbor who lives behind her house was shot in the back. Not long ago, there was a shooting nearby, and she remembers calling out to her 8-year-old granddaughter.

“‘Lay on the floor, lay on the floor,’” Milton recalled. “You’re stressed all the time, especially when you have children that want to go outside.”

One day last week, on the 18th floor of the Hennepin County Government Center, the prosecutors in a wood-paneled courtroom called a use-of-force expert from the Los Angeles Police Department. LAPD Sgt. Jody Stiger was blunt when asked about Chauvin’s actions when detailing Floyd: “My opinion was that the force was excessive.”

During testimony, Nelson walked outside with other community organizers around the blocks surrounding the courthouse, wanting to be close to a trial that has riveted a country and whose verdict will probably set the tone in coming years between police and Black and Latino communities.

He scrolled his phone for updates.

“This is a moment,” he said. “If there is a murder conviction, I’m optimistic police will wake up and clean up their act.”

Special correspondent Tania Ganguli contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.