Lots of talk, still too little change to policing three years after George Floyd’s murder

- Share via

The relationship between the American people and the police who protect, serve and sometimes oppress them was already under stress when Officer Derek Chauvin kneeled on George Floyd’s neck for nine minutes on a Minneapolis street on May 25, 2020.

Police have been disproportionately killing unarmed Black people throughout the nation’s history, but it immediately became clear that Americans saw the Floyd murder as something different. Perhaps it was because nerves were frayed and people were on edge after nearly three months of lockdown to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, or perhaps because recent high-profile police killings like the shooting of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ky., two months earlier weighed heavily on the spirits of many. Whatever the reason, the Floyd murder and its aftermath shook the nation.

Flashes of violence marred protests throughout the summer. The national debate over policing became increasingly polarized and partisan as President Trump made law and order the cornerstone of his reelection campaign — and dispatched federal officers and agents to “Democrat-run cities” to fight crime that he said police could not, because they supposedly were hamstrung by liberal mayors.

Protesters jubilantly declared a police-free zone in Seattle, but it was soon beset by crime, including deadly shootings, and officers returned. Civilians “patrolled” streets amid protests in cities such as Kenosha, Wis., where Kyle Rittenhouse shot two men to death and wounded another.

The Times Editorial Board examines the reckoning of the last year and considers what it means for policing and protest in Los Angeles and elsewhere.

The issue of the proper role of police was central to the civil unrest. Policing took a key role in the discussion of the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol, to some extent flipping the narrative as Trump supporters chided Capitol Police officers for supposedly being on the wrong side, and skeptics of policing hailed the officers for standing firm. But there were a few off-duty officers from around the nation among the rioters as well, and some Capitol invaders carried the “thin blue line” flag that symbolizes police sacrifice but has come to be seen as a symbol of white supremacy as well.

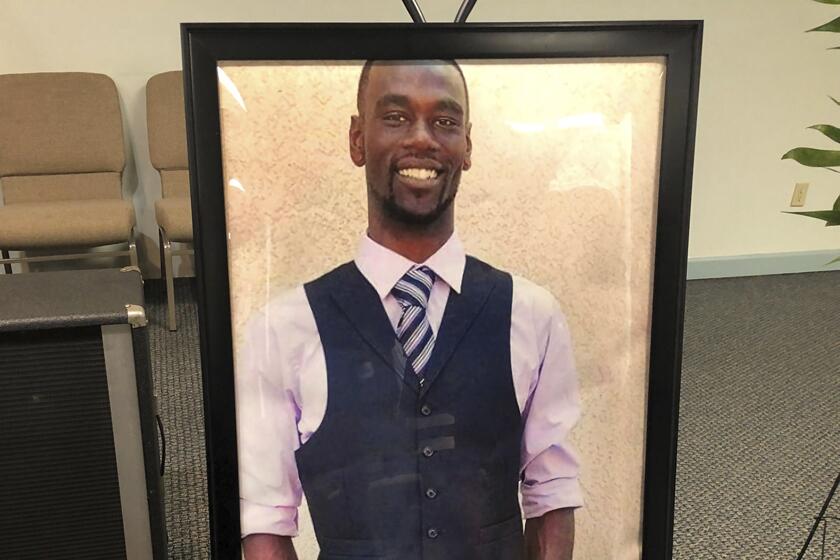

So where are we now, three years after the Floyd murder? Meaningful progress in altering unnecessarily deadly police conduct is hard to identify. The year began with a spate of deeply troubling police killings, including three in Los Angeles and, the same week, the beating of motorist Tyre Nichols, who was also subjected to mace and tasers, near his home in Memphis, Tenn. Nichols died several days later.

Yet there are developments that are noteworthy, if not necessarily breakthroughs. One of the most important may be a statement issued on March 2 by the Los Angeles Police Protective League listing 28 types of calls for which they’d prefer not to be responsible. They include parking violations, panhandling, mental health calls, welfare checks and a variety of other services that police have traditionally performed.

The list is not identical to the set of demands by abolitionists who want to untether city budgets and communities from police. But there is some overlap.

The Tyre Nichols beating video is being cited as evidence that race isn’t a factor in excessive police force, policing can’t be reformed, a few bad cops are ruining the profession, nothing has changed in law enforcement, and victims of police violence are to blame. But the video shows none of that.

The Police Protective League is an employee union and not in command of the department, so its position on how its members should or should not be deployed has little direct or immediate impact. But its stance is important because police unions so often resist any reduction in their footprint. And Chief Michel Moore has also called for his officers to be relieved of duties that can be safely performed by professionals in other fields, such as mental health outreach workers.

Similar discussions are unfolding in cities across the country regarding the kind of police presence that does not relinquish the responsibility for public safety to the Kyle Rittenhouses of the world or to police-free districts like Seattle’s short-lived autonomous zone.

Some proposed policing changes are little more than political power plays, along the lines of Trump’s actions during the summer of 2020. Count among those the law written by Mississippi’s GOP-controlled Legislature to substitute state police for city officers in a large area of Jackson, the capital city. Some discussions are potentially more constructive, but still in the earliest phases, with many details as yet unexamined. Discussions in Los Angeles, and the similarity between some parts of the abolitionist and police union’s to-do lists, fall into that category.

The fault lines that widened in the aftermath of the Floyd murder are troublesome and continue to present serious peril as the nation struggles to deal with public safety and the role of police. But there are opportunities for consensus-based constructive change, if we’re smart enough to grab them.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.