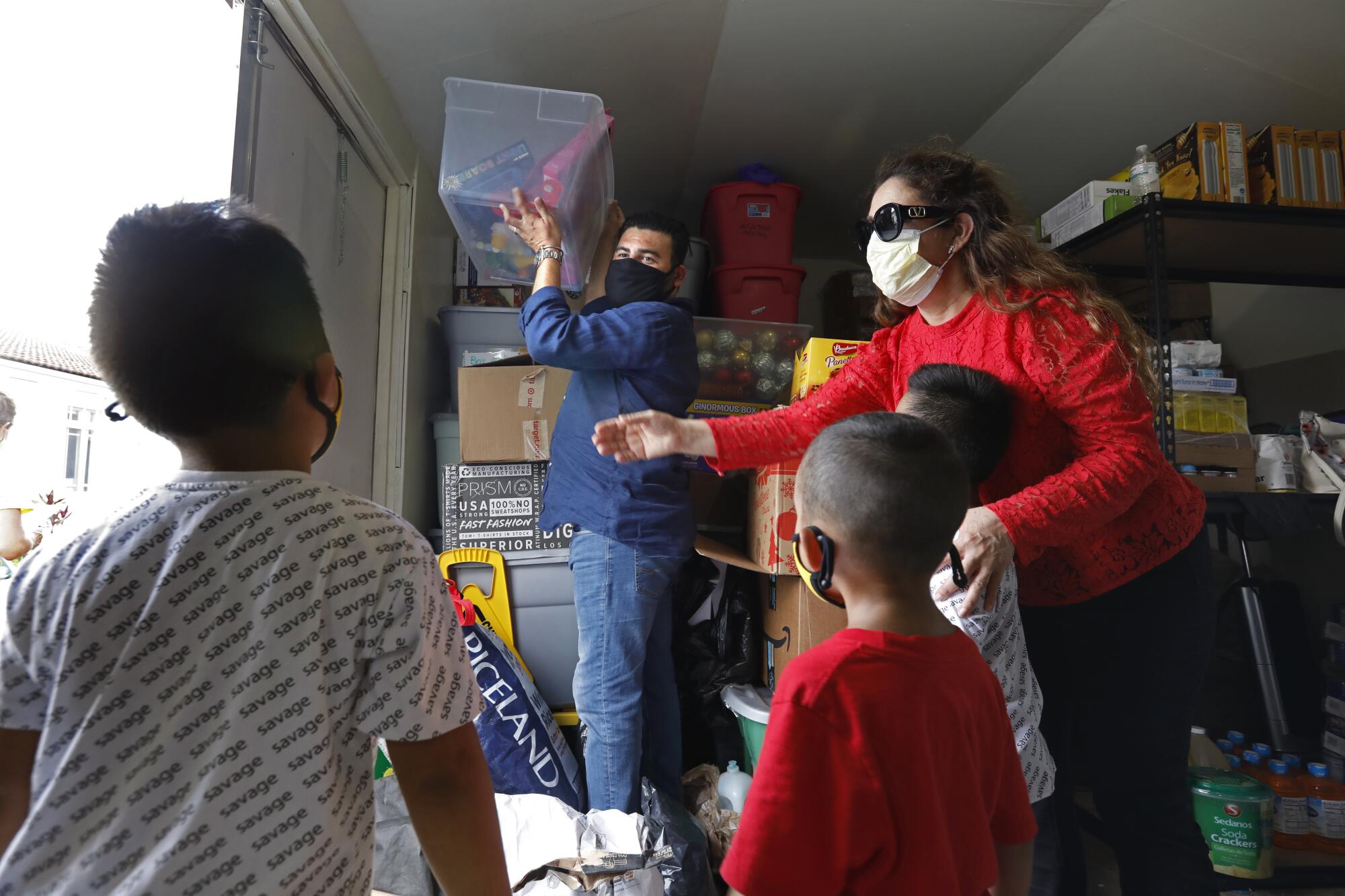

Nicaraguan American Nora Sandigo helps children who have crossed the border on their own to join families in the U.S.

- Share via

MIAMI — The Great Mother’s phone is ringing.

It’s after dark and Nora Sandigo has retreated from a tropical storm into her hacienda-style ranch house on the southern outskirts of Miami. The Nicaraguan American businesswoman has spent the day greeting migrant families on her patio, distributing food and toys as clouds loomed.

For years, Sandigo has kept migrant children out of foster care by assuming power of attorney or guardianship over them after their parents have been deported. These days she’s also helping children who have crossed the border on their own to join families in the U.S.

She picks up the phone.

Immigration lawyer Nicolas Aguado is calling to say one of those families is about to be reunited.

“What is the good news?” Sandigo says in Spanish. “Tomorrow Catalina’s girls arrive?”

Aguado says Catalina Aviles’ daughters — ages 3 and 5 — will be released from a federal migrant shelter where they’ve been held for a month after crossing the border illegally. The Mexican girls are scheduled to fly with a federal escort the next morning to join their mother in Austin, Texas.

“When the parents don’t know what to do, when they’re afraid or the process is difficult, they call me,” Sandigo says as she rushes to book a flight to Austin to coordinate the reunion. “I have to always be ready with a bag packed.”

Sandigo knows what it’s like to be on an uncertain journey. The second-eldest of seven children raised in the rural town of Comalapa, Nicaragua, she was 15 when her parents decided she had to escape the country’s revolution in the 1980s. She eventually pressed north, and now — a mother of two grown daughters with a good life in an adopted land — she sees herself in the children she is helping.

As of Thursday, there were 19,537 migrant children at federal shelters, where they have stayed for an average 37 days. More than 80% of these children have family in the U.S. Some parents have had to wait more than a week to talk to their children by phone, even longer for federal officials to tell them the cities and shelters where their children are being held.

Sandigo — who is known as “La Gran Madre” and has had power of attorney for more than 2,000 children — receives hundreds of phone calls a week from a growing list of migrant families. Her words are swift; she nods her head. Each case, although distinct, has the ring of familiarity she has heard for decades.

Aviles’ daughters traveled with their 18-year-old sister. After they crossed the U.S. border, the small girls were separated from their sister by Border Patrol. Children who arrive with relatives other than their biological parents are routinely placed in federal custody until released to their parents or another sponsor vetted by the government. Aviles’ eldest daughter was sent back to Mexico, her younger sisters to shelters in San Antonio and, later, New York City.

Aviles, 41, a restaurant worker from Michoacan, crossed the border illegally nearly a year ago and now lives outside Austin. In a phone interview this week, she said she didn’t want her daughters to have to make the journey. But in January, her eldest answered a knock at the door and was raped by a stranger. Getting her daughters out of Mexico seemed the only way to protect them, Aviles said.

After the girls arrived at the border, she had trouble locating and claiming them.

“They didn’t give me any hope for when they would be released,” Aviles said of government staff she spoke with. “I said to them, ‘Don’t you understand what it’s like to be a mother?’ They said, ‘You have to wait. We can’t do anything else for you.’ It’s very hard to get information.”

Aviles had read Spanish language news reports about Sandigo and emailed her.

“I’m desperate, please help me. I am going crazy with all this. My daughters call me crying to come get them, that they miss me,” she wrote.

As more young migrants arrive at the U.S. border alone, overcrowding at Border Patrol facilities and delays in releasing the children worsen.

This week, after Aviles was reunited with her two younger daughters, she credited Sandigo’s group: “They were the first people who helped us,” she said.

The list of federal shelters has been growing exponentially in recent weeks, with new ones opening weekly at military bases, convention centers and former oil field camps. A shelter capable of housing thousands of children a few miles from Sandigo’s house in Homestead, Fla., is on standby, having drawn criticism and protests in the past.

Sandigo remembered her own migration when she escaped a war between Sandinista revolutionaries and right-wing Contra forces in Nicaragua. “I felt like any moment they could knock on my door and kill me,” she said. She fled to the capital, Managua, then to Venezuela and finally, with a visa, to Miami in 1988.

“We had to save ourselves,” said Sandigo, whose father died in 1990 of natural causes and whose mother joined her the following year in Florida.

Sandigo founded Nicaraguan and migrant advocacy groups, and married a fellow Nicaraguan from her hometown. She started a small nursing home and a plant business that cultivates banana palms, mangos and guavas — fruit trees she loved as a child. In 1996, she became a U.S. citizen and the lead plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit to get the U.S. to grant legal residency to Nicaraguans.(Congress passed a law admitting them the next year.)

U.S. officials recorded 100,441 encounters with migrants at the border last month — nearly triple the total in February 2020.

A Peruvian migrant mother who had been living in the U.S. illegally noticed news reports about the lawsuit. She called Sandigo from an immigrant detention center and asked her to take power of attorney for her two children, to prevent them from being placed in foster care once she was deported.

Sandigo agreed. And her phone has kept ringing.

Sandigo said she has helped more than 200,000 migrants so far. She stays in touch with the children she represents, watching as they graduate from high school, college, nursing school and, in one case, Georgetown Law School. She and her foundation have filed a number of lawsuits on behalf of children and their migrant parents, including a 2015 brief with the U.S. Supreme Court in support of Deferred Action for Child Arrivals.

“When the parents don’t know what to do, when they’re afraid or the process is difficult, they call me.”

— Nora Sandigo

She has been to the White House a number of times, most recently in 2019 to meet with then-Vice President Mike Pence.

Greeting families last Sunday in a red lace blouse and low heels, her hair long and loose around her shoulders, her makeup intact despite the heat, she fed children hot dogs and introduced parents to Aguado, the lawyer. She listened and occasionally shared her experiences navigating the U.S. immigration system.

Migrant parents fearing deportation under President Trump often turned to Sandigo for help. She has two filing cabinets in her house filled with cases of children whose parents gave her power of attorney or guardianship. At least a hundred were in California. Some of those she’s helping now are from Nicaragua.

“Their situation is more or less my situation when I came to this country,” Sandigo said, referring to children fleeing the regime of Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega, a former Sandinista, who decades later still controls the country. “I was in real danger. I could be dead at this point, if I didn’t have the opportunity to get out. My father did everything in his power to send me out of the country and protect my life.”

Three years ago, Sandigo joined fellow Nicaraguan exiles in a complaint with the United Nations against the Ortega government, alleging crimes against humanity, including violent oppression of anti-government protests, some by Christian groups (Sandigo is Catholic). Amnesty International and other human rights groups have made similar allegations. The U.S. has imposed sanctions, but Ortega has not relented.

“Nicaragua is being held hostage,” Sandigo said.

Sandigo’s ranch became a refuge for migrant families during the pandemic. Friends installed a mobile home where a Guatemalan single mother is now living with her three children. Volunteers gather at the house to help her deliver groceries to more than a dozen migrants who are homebound after testing positive for the coronavirus. Many can’t get vaccinated against the virus at local clinics, which require state identification Florida won’t issue to migrants who don’t have a government-issued photo ID or proof of residency.

Sandigo compared the flurry of calls seeking her help to Trump’s first year in office, when many migrants were deported under a “zero tolerance” policy.

“We are returning to that time,” she said. “There’s a wrong perception in the community that we have open borders for everyone, that everyone coming will be protected.”

Sitting on Sandigo’s patio Sunday, recently arrived migrant Faustina Hernandez asked if she could apply for asylum to legally stay in the U.S. with her family. Aguado, the immigration lawyer, told them they had a year to apply and explained how to go about it.

Hernandez, 27, left Guatemala in January with her daughters, ages 8 and 10, heading for her husband, who has been a farmworker in south Florida for the last seven years. Hernandez’s mother had been diagnosed with cancer, and she said she wanted to work in the U.S. to support her. She and her daughters crossed the Arizona border in February, were returned to Mexico by Border Patrol, then crossed again last month and made their way to Florida.

“It’s like me in the past,” Sandigo said on why she reunites families. “It’s my mission.”

She serves the family lunch, then sits with them, helping the girls draw birds, including the Guatemalan quetzal, a reminder of Central America, the land they left.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.