Lawyer who took part in Tiananmen Square protests is killed in his New York office

- Share via

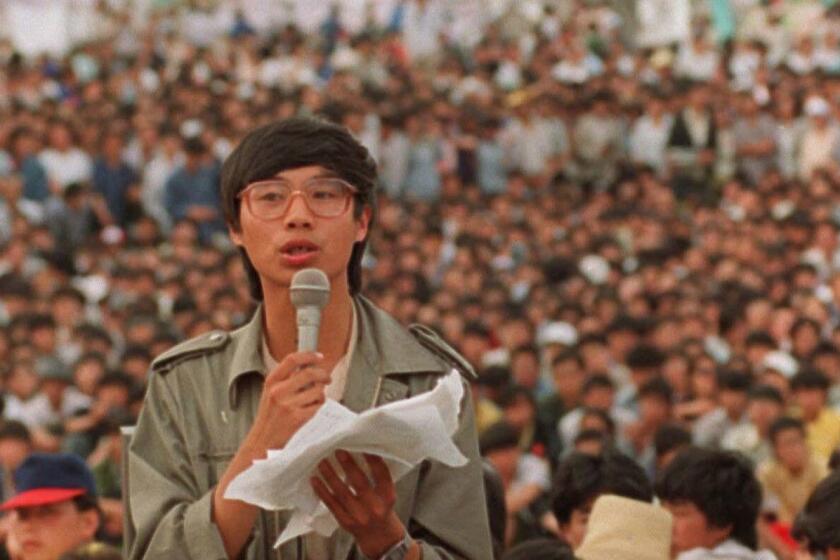

NEW YORK — A dissident legal scholar who was jailed for two years in China after participating in the 1989 Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests was killed Monday in his law firm’s office in New York, where he had settled after seeking asylum in the U.S., police said.

Li Jinjin, 66, was stabbed to death in the city where he had long worked as an immigration lawyer, even as he continued to advocate publicly for the many people jailed or killed by Chinese authorities during the 1989 pro-democracy movement.

An arrest was made in Li’s slaying. Police said Xiaoning Zhang, 25, was taken into custody and faces a murder charge. It wasn’t immediately clear when she would be arraigned or if she had retained an attorney.

Chuang Chuang Chen, chief executive of the China Democracy Party, and lawyer Wei Zhu, a friend of Li’s, told the New York Daily News that the killing might have stemmed from Li’s refusal to take on Zhang as a client.

Zhang came to the U.S. in August on a visa to go to school in Los Angeles, Chen told the Daily News.

Li, who also went by the first name Jim, was often quoted in recent years by news organizations looking for insight or commentary on the Chinese dissident community or on relations between China and the West. As an immigration lawyer, he also represented some Chinese expatriates living in the U.S. who were considered fugitives by that country.

Everyone remembers China’s “Tank Man,” who stood with bags in his hands, blocking a line of tanks withdrawing from Tiananmen Square a day after the fatal June 4, 1989, military crackdown against pro-democracy protesters.

“He was one of the best men I have ever known,” Zhu told the New York Daily News. ”If he hadn’t left China, he could have been a famous lawyer. He could have been a judge.”

Prior to his imprisonment for protesting in 1989, Li had been a legal advisor to an independent labor union that had challenged China’s government on worker rights.

“I can’t believe it. She not only destroyed his life, but the hope of our community,” Zhu said. “He wanted to realize democracy in China. He will never realize that dream.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.