Ebola outbreak often leaves children alone and terrified

- Share via

Reporting from Suakoko, Liberia — The small, frail girl was slumped in the street outside a row of shops when an ambulance picked her up.

Anna Singbeh, 11, was terrified. The child, from the town of Totota in central Liberia, had seen her mother sicken with the Ebola virus and swiftly die. By the time she fell ill, there was no one left to help.

She couldn’t walk from the ambulance into the International Medical Corps Ebola treatment unit in Bong County. Dr. Pranav Shetty, clad in yellow bio-suit and white hood, goggles and mask, picked up the slight figure, carried her into the unit and tried to figure out what to do.

She was too sick to tell him more than her name and age, said Shetty, the IMC’s international emergency health co-coordinator. She was given a bath. Her clothes were burned and she was given fresh ones.

But saving Anna Singbeh was not going to be easy.

As the Ebola virus sweeps through Liberian villages, through its towns and cities, whole families are being cut down by the disease. Parents who die leave behind children no one wants to care for, rejected by neighbors and relatives, who order them to stay away. With an acute shortage of beds, the lucky ones are picked up by ambulance and taken to treatment units. Many of the rest die on the streets.

In Monrovia, the capital, all the Ebola treatment unit beds are full, vacancies opening only as patients die or survivors are discharged. The IMC center, which opened just last week, is one of two in Liberia with available beds. It has admitted 26 patients, seven of whom have died. Two of the dead were children.

The main priority in the treatment units is to keep the workers safe. Next is to isolate infectious patients to prevent spread of the disease. Providing decent care has to come third.

Health workers in heavy, cumbersome suits designed to protect against infection are permitted to spend no more than an hour at a time in the stifling heat of the wards, and with many patients acutely ill, patients are alone most of the time. For children left without parents or family, it is a lonely, terrifying time.

“All the patient sees is a pair of eyes looking at them. It’s just a pair of eyes in an anonymous suit,” Shetty said.

“It’s harder to interact with the patient in a normal way. Your mask gets wet and it’s hard to breathe. Your goggles fog up,” he said. “I do think it’s hard for children. It’s very difficult to console them because they’re upset. You can’t do what you would normally do, which is to sit on the bed and play with them, console them. It’s tragic.”

During the hour of treating patients in temperatures that regularly hit the mid-90s, many staffers lose up to three pounds in body fluids, their boots filled with puddles of sweat. It’s physically difficult, and dangerous, for them to spend longer in the high-risk zones.

In some treatment units, such as the Doctors Without Borders center in Monrovia, mothers sometimes choose to enter the high-risk zone to care for young children, who couldn’t survive alone. That gives those children a better chance of survival, doctors have observed, but at a risk to their parents.

When Anna Singbeh arrived, Shetty found himself with few options.

“She sat on a chair and then got off the chair onto the floor. I carried her to her room. I tried to hydrate her. I tried to feed her,” he said.

“By the time she came here, she was psychologically tortured,” said Patrick Githinji, a Kenyan nurse who couldn’t help thinking of his own 10-year-old daughter when he looked at Anna. “She’d lost her mother. She was left alone in a shopping center. She couldn’t talk.”

Already they had another difficult case: A 14-year-old boy, Elijah Kollie, was refusing to take his medicine or eat.

Somehow, despite their suits, IMC counselors had managed to form a bond with the boy.

He’d been living under a foster care arrangement with his aunt, who worked in a pharmacy with her husband, treating Ebola patients. He watched his aunt, uncle and cousin die, one by one, within 24 hours. Rejected by another aunt and the neighbors, he returned to his parents.

IMC counselor Garmai Cyrus could hardly believe what she was hearing. Elijah told her his father refused to let him into the house, telling him to sleep in the school. The schoolmaster chased him out of the school. He slept two nights in a cellphone sales kiosk, Cyrus said, without blankets or food.

Finally, someone took him to a clinic, and he was picked up by the IMC ambulance.

“He was tired when he got here, so tired,” said Cyrus.

“He said, ‘My aunt got me infected. If it wasn’t for her, I wouldn’t be here today.’”

The boy was so miserable that it was hard to reach him. Cyrus, clad in her bio-suit, worked on persuading him to eat and take his medicine. Soon, he started calling her “Auntie.”

“He said to me, ‘Auntie, you imagine when I came, my father said I couldn’t sleep in the house. They said they didn’t want me to go near them, they told me to go away,’” she recalled.

Cyrus found her goggles fogging up as tears welled. “I had to turn away and leave,” she said. “I was ashamed, because it’s not really right to let a patient see your weakness.”

Cyrus and her colleague, another counselor, J. Harris T. Kolli, persisted. For three days, Elijah didn’t eat or take medicine.

“He was so downhearted when they brought him here,” Kolli said. He knew that if the boy didn’t make an effort to help himself, he’d die.

“I ask him, ‘Here at this place when you have Ebola, we expect two results. Either you live or you die. Which one do you prefer?’ ”

“I want to live,” Elijah told him.

“If you want to live, eat, take your drugs,” Kolli said. “When you have symptoms, you tell us.”

It was different after that. “I was surprised. He ate all the food he was given. He was sitting up. Now he’s coming up fine,” Kolli said, sounding more like a joyful uncle than a health worker surrounded by death.

No one in the boy’s family has visited. The cellphone numbers his parents gave health workers don’t work. Staff members are increasingly confident Elijah will survive, though Cyrus frets about how he’ll fare if he does, whether he’ll be rejected again.

“He’s already been hurt so much,” she said.

Saving Anna proved impossible.

With no parent to get her to the hospital in time, she was very sick on arrival. She couldn’t take medicine. When Shetty tried to insert an intravenous drip, she panicked and fought.

It was unsafe to persist: One slip of the needle could pierce the doctor’s bio-suit, cut his skin and infect him. He had no choice but to stop.

“There’s not much you can do past that,” Shetty said.

Anna was bleeding from her mouth, getting weaker. Her final hours were awful. She died, less than 24 hours after she came in, afraid and alone.

IMC burial team members sprayed her body with disinfectant, sprayed the inside of a body bag and eased her into it, zipped it up, sprayed again. They sprayed inside another body bag, placed the first bag in it, sprayed again, zipped, sprayed again, then prepared a third body bag.

The team carried her down a damp forest track to a shady glade with a row of waiting graves.

Four gravediggers shoveled the moist red clay, which fell with soft thuds into her grave. A group of other diggers chatted nearby, oblivious to the tragedy.

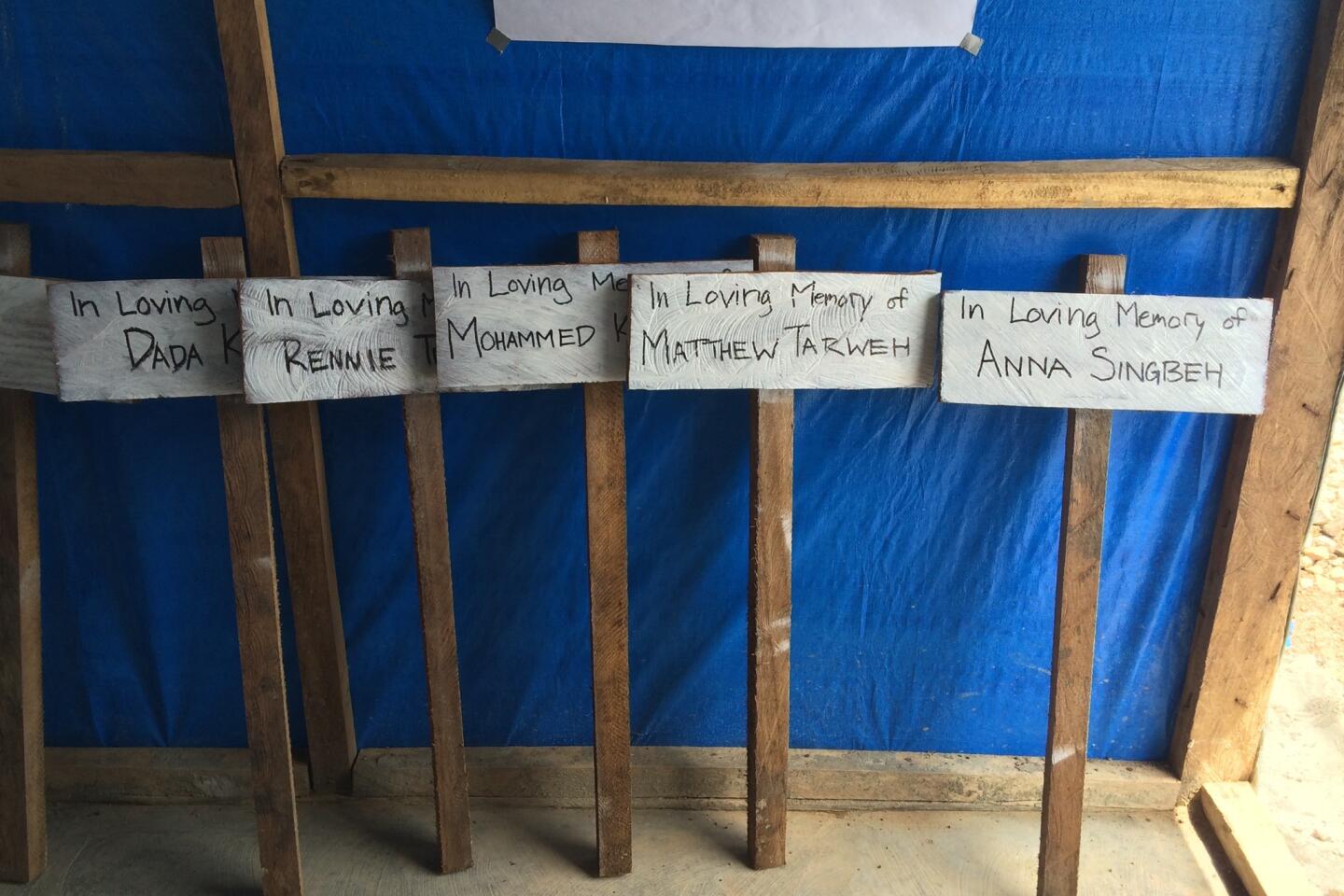

Later, the gravediggers planted a wooden marker. It read, “In Loving Memory, Anna Singbeh.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.