In Rwanda, ‘reeducation’ means detention for homeless, hawkers and other undesirables

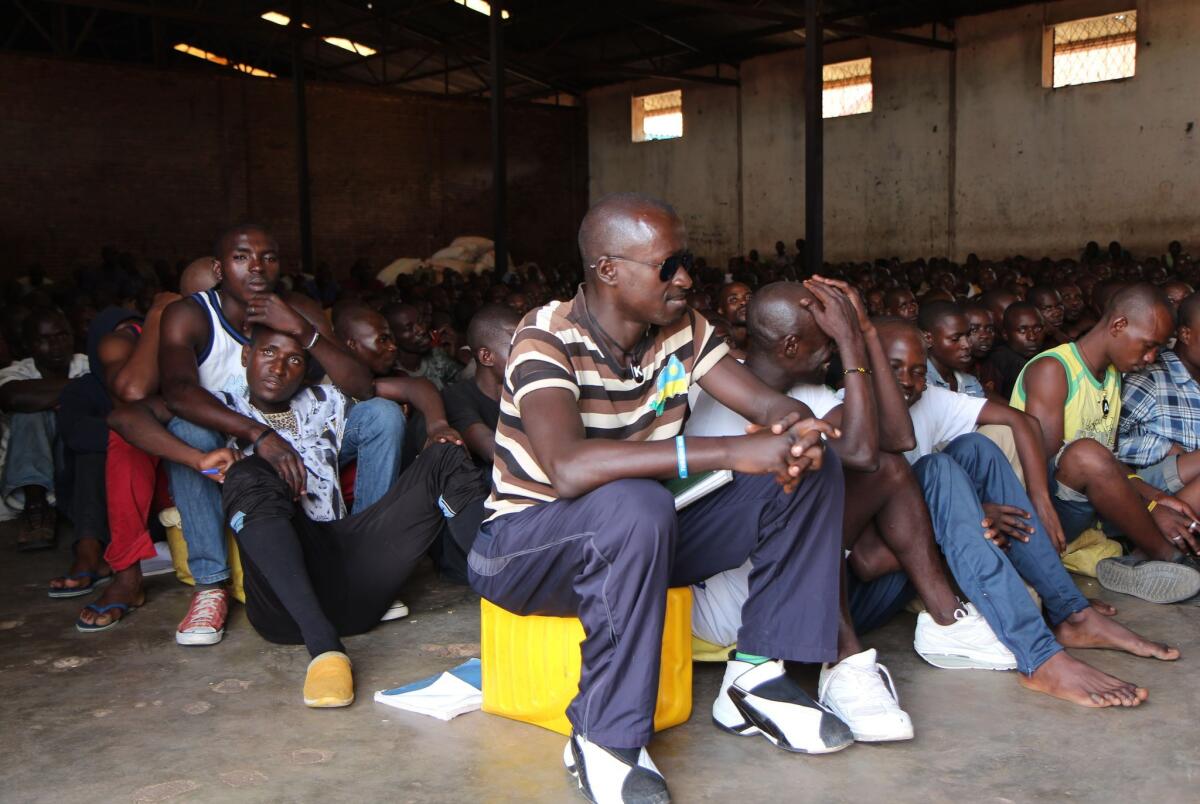

Men sit in the Gikondo Transit Center in Kigali on Sept. 24. A Human Rights Watch report released during the day accused Rwanda of rounding up “undesirables,” including beggars and prostitutes, and holding them in the grim center.

- Share via

Reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa — In Rwanda’s creepy Big Brother speak, the facility behind the high red-brick walls of a disused factory in the capital is called a “transit center.” Its job is “reeducation” and “rehabilitation.”

But it’s more like a prison, according to former detainees. Inside its walls, street beggars, homeless people, drunks, street hawkers, prostitutes, “idlers” and others, many of them the poorest of the poor, are held without charge, some for months, according to a report Thursday by Human Rights Watch.

The name for staff members at police-operated Gikondo Transit Center who mete out regular beatings? “Counselors.”

“They say Kwa Kabuga is a reeducation center, but it is a prison,” one former detainee told HRW in February 2014, using the center’s nickname. “So I ask, why not call this place a prison?”

The ex-detainee was one of 57 interviewed by the rights group. Their names were not published because of possible recriminations.

According to Carroll Bogert of HRW, Western visitors — often tourists on their way to see mountain gorillas — love Rwanda’s capital because the streets are so spotless and tidy.

“Kigali is often praised for its cleanliness and tidiness, but its poorest residents have been paying the price for this positive image,” said Daniel Bekele, African director for HRW. “The contrast between the immaculate streets in central Kigali and the filthy conditions in Gikondo couldn’t be starker.”

Police appoint the counselors, who walk around with sticks. Many of them are detainees who have been in the center the longest.

“If you get sick, the counselor can beat you until you are better,” said one former detainee.

“The counselor beat us like cows. He always has his stick, and he can beat you if you move. If you get into a dispute for a place in the room, you are beaten,” said another former detainee interviewed in June 2014.

Some described how counselors used the beatings to extort bribes. Many were beaten as they waited in line to use the latrines.

Also inside the walls are the young children of some detainees, and the parents sometimes pay the price for their behavior.

“If your child goes to the toilet on the ground, then it is serious. They will beat you and shout at you: ‘You are making this place dirty!’ ” one mother said.

“You just hand your child to a friend and you lie down. Then the counselor hits you,” another mother said.

The corruption found in many parts of the continent is rare in Rwanda, and progress on development goals since the country was ravaged by genocide in 1994 has been impressive.

But under President Paul Kagame, Rwandan society has grown increasingly oppressive. There is little room for dissent and scant media freedom. Opposition figures are jailed, and many have fled into exile. Several have been slain abroad, with Rwandan security agents suspected in the killings.

The country has a compulsory national cleaning day on the last Saturday of the month, when everyone must join in and clean the streets and cut the grass.

Local defense units enforce strict social rules, detaining anyone involved in disruption of public order. Those who fall foul of the system can end up in Gikondo.

Kagame, along with other leaders in Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of Congo, appears determined to run for a third term in office, which requires changing the constitution. The reason, often cited when leaders engineer third terms to stay in power, is popular demand.

In Rwanda, 60% of voters — 3.7 million — signed a petition calling for constitutional changes so Kagame can reign on. And when lawmakers toured the country to gauge public sentiment, they found just 10 people who were willing to oppose Kagame’s third-term bid.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

Sept. 24, 2:30 p.m.: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that 60% of the population signed the petition calling for constitutional changes. It was signed by 60% of voters.

------------

Police and local defense units carry out regular mass roundups of undesirables — including street hawkers, who practice a common form of survival across Africa. Detainees are loaded onto trucks, dozens at a time, and taken to police cells and later transferred to the transit center without any legal process, according to the HRW report.

“They take people in waves. Sometimes it will be a few days with nobody taken, then they arrest many people,” one former detainee said.

The report calls the detention of homeless and poor people for minor social infractions illegal, citing the Rwandan justice minister as telling the organization there was no legal framework to detain people at Gikondo. But the minister, Johnston Busingye, released a statement Thursday saying that all the country’s facilities were run properly, according to U.N. standards, and denying any illegal detention.

Rwandan officials told HRW that Gikondo is clean and provides good food, sanitation and recreational facilities. However, the rights group found that conditions in the center were “deplorable and degrading,” with detainees lacking adequate food and getting water only sporadically. They are often forced to sleep on the floor without mattresses, the group said.

“Although labeled as a center for rehabilitation by the government, and allegedly staffed with counselors and health-care workers, access to medical treatment at Gikondo is sporadic, and rehabilitation support, such as it is needed, is nonexistent,” the report said.

Some street vendors and sex workers were arrested and sent to the center many times because they continued to pursue their trades.

“They say they send us there to correct us or to get us to abandon our trade, but we don’t have money to start a restaurant or a bar,” a female vendor told researchers. “The police just say, ‘Abandon your work,’ but what can we do?”

In most cases, detainees had to pay a bribe to be freed, the report said.

Busingye said HRW had deliberately misled people with the false report, undermining Rwanda’s efforts to provide a better life for its citizens. In an ominous note, he accused the organization of breaching the memorandum of understanding with the government that allows it to operate in Rwanda.

“It has become increasingly clear that HRW refuses to engage through the mechanisms established under the [memorandum of understanding] and instead seeks to spread falsehood and speculation,” he said.

Follow @robyndixon_LAT on Twitter for news out of Africa

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.