Surviving on a little luck and lots of street smarts

- Share via

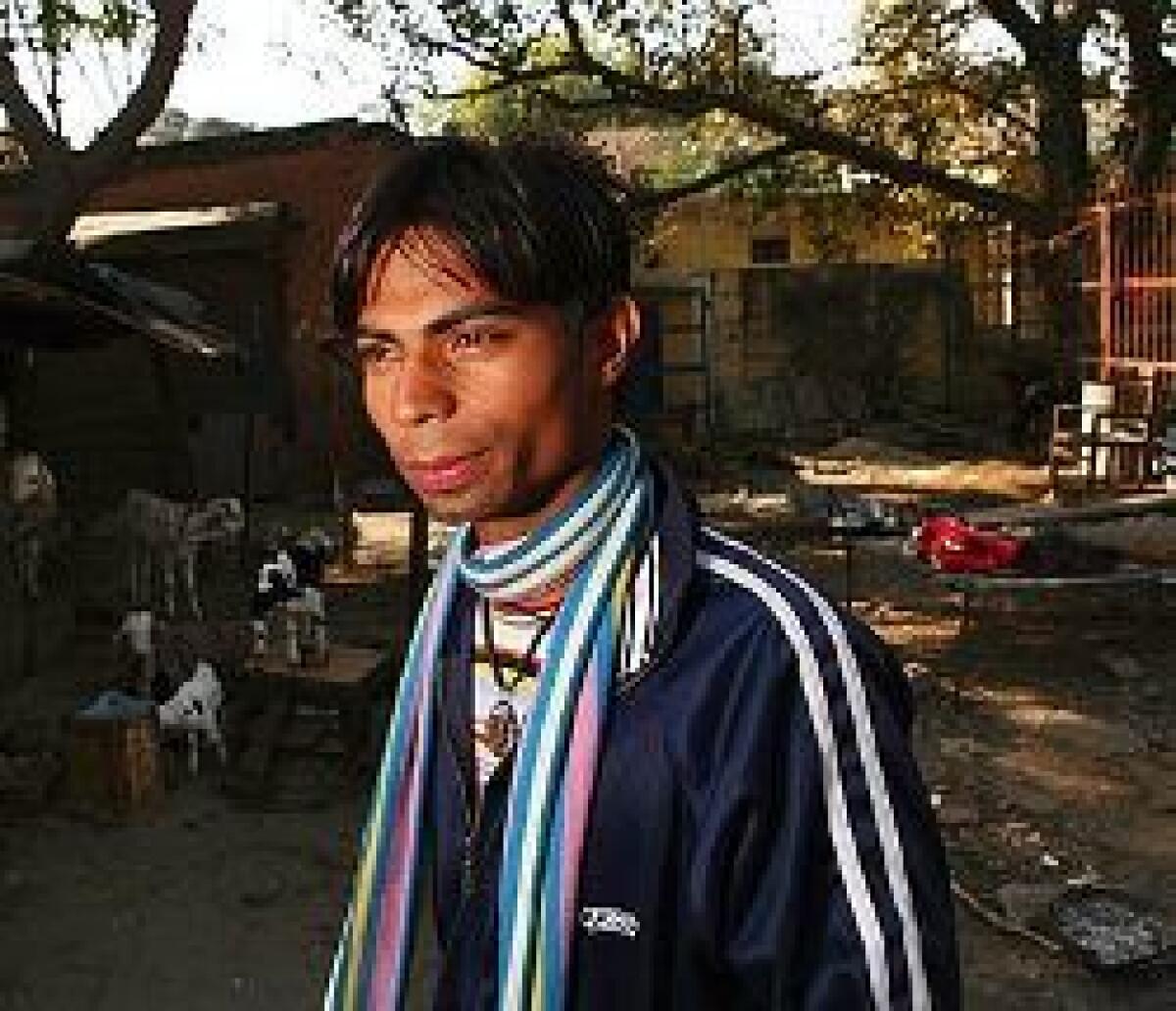

Reporting from New Delhi — Shekhar Sahni has a cocky air, a music player filled with Hindi tunes and a swagger befitting someone who’s beaten the odds in a culture where it’s drummed into you early to accept your fate.

The 21-year-old grew up on India’s rough streets and dreams of becoming a Bollywood star. Sahni liked the hit film “Slumdog Millionaire,” which is up for 10 Oscars on Sunday, including best picture, but he was not particularly impressed by the way it depicted street life.

One thing the film got right, said Sahni, who works for a New Delhi charity, was the importance of on-the-street training.

“The streets make you smart,” he said. “You grow up fast.”

At any given time, there are an estimated 300,000 children on the streets of Delhi living with their families, and 50,000 on their own, said Praveen Nair, managing trustee with Salaam Baalak Trust, which helped Sahni get off the streets. Government centers and charity networks such as Salaam Baalak are overwhelmed, while gangs, with their promises of fancy clothes and easy money, often are far better recruiters.

Sahni was born in Kalyanpur village in Bihar, an eastern state notorious for its poverty and corruption. His family was middle-class, he said, but his father drank and beat him. He says himself that he was not a model son, considering his fondness for smoking, gambling and endless TV viewing.

At age 12, fueled by impetuous rage, he stowed aboard a train to New Delhi with some money he’d stolen -- about $10.

As he sat on the platform wondering what to do, a man named Dutta approached him with an offer of help. Sahni had heard about thieves who drugged kids, stole their money, even cut off their limbs and forced them to beg. But he was desperate -- and lucky as it turned out. Dutta fed him, pointed out a place to sleep in the rail terminal and taught him to “rag pick,” or scavenge garbage piles for recyclables.

Camaraderie

Sahni joined three other homeless boys, sleeping under a stairway on Platform 12 or on the roof of a kiosk on Platform 5 as streams of people rushed past to their families, weddings, business meetings. Despite occasional bouts of homesickness, he felt great freedom in living on the street.

“It was fun,” he said with a laugh. “Really fun.”

The four boys didn’t pool what they earned scavenging, selling the items at dingy recycling stalls near the station. But working in a pack prevented other ragpickers from muscling in on their turf. On a good day he made $6. But $2 was more typical.

Some of their best hauls came from the long-distance trains arriving on Platform 1, which had better-quality refuse. They’d scoop up anything of value, including the railroad’s metal trays, before cleaners or railway police chased them away. Twice Sahni was badly beaten by police, who tended to catch the slow, weak and inexperienced. After that he was more vigilant.

Girls are chewed up more quickly than boys, said Sahni, often becoming pregnant or sliding into prostitution, sometimes under pressure from gangs or their own parents desperate to raise money for drugs. And some of his friends, both boys and girls, faced sexual abuse in city shelters that house adults and children together, he added.

What little sex education many street children receive often comes from their peers, he said.

Sahni, who never begged because he considered it beneath him, said the trade is well organized. Thugs recruit street kids and some women “rent” babies for beggars to hold for $1 to $2 a day, often drugging them so they don’t cry.

After six months of rag-picking, Sahni met a man named Rahul, who hired him to sell the home-brew he made from water and chemicals, mostly to rickshaw, taxi and bus drivers. The job paid $13 a month, less than rag-picking, but Rahul let him live with his family.

Sahni said he also learned to overcharge customers and pocket the difference.

After six months, he got into a fight with Rahul and returned to the railway station. But by that time Dutta was in jail and the others he knew had disappeared.

As he sat one day trying to figure out what to do, a counselor with Salaam Baalak, which was set up by director Mira Nair with proceeds from her 1988 film about street children, “Salaam Bombay,” approached him, offering him food, shelter and clothing.

Sahni was wary of losing his independence. Then the man offered the clincher: He could also watch TV.

A few months later, he returned to his village to see his parents, five brothers and two sisters. They were relieved to see that he was alive, and many in the village urged him to stay. But after a few weeks he went back, convinced that his home and opportunities were in Delhi.

“I felt like an alien there,” he said.

Drug addiction

At 16, even with the charity helping him, he fell into drugs. A guy he had met who impressed him by speaking English well asked him if he wanted to try sniffing fluid of the sort used to correct typing mistakes. He jumped at the chance, impressed by his new friend, who he hoped could teach him English.

As Sahni described his past, he pointed out two small shops down Sangtrashan Lane in Paharganj, adjacent to the station, that sell correcting fluid to children, which is illegal. A young man staggered by, his face covered with the fluid.

“Come any time,” the shop owner said. “We always have supplies. Police? Look, the station is just over there. There’s no reason to worry.”

Sahni said he became hooked on the fluid. He’d pour it into a handkerchief and breath deeply or blow it through an electric fan, then watch the spinning blades for hours. “I lost my way,” he said. “It can destroy everything, lungs, brain cells.”

Eventually he landed in a rehab facility. He stopped sniffing, albeit with some relapses.

Sahni has been working for several years to help street children. The charity sets small goals, administrators said: feeding kids, encouraging them to wash at faucets, to draw -- anything to get them off the street for a few hours.

He recently started studying French and Spanish in hope of becoming a professional tour guide if Bollywood stardom is not in the cards.

“Everyone dreams, but reality is reality,” Sahni said. “You also have to be practical.”

Pavitra Ramaswamy of The Times’ New Delhi Bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.