A vision for a new era: Brazilian sees his museum as a path to change

- Share via

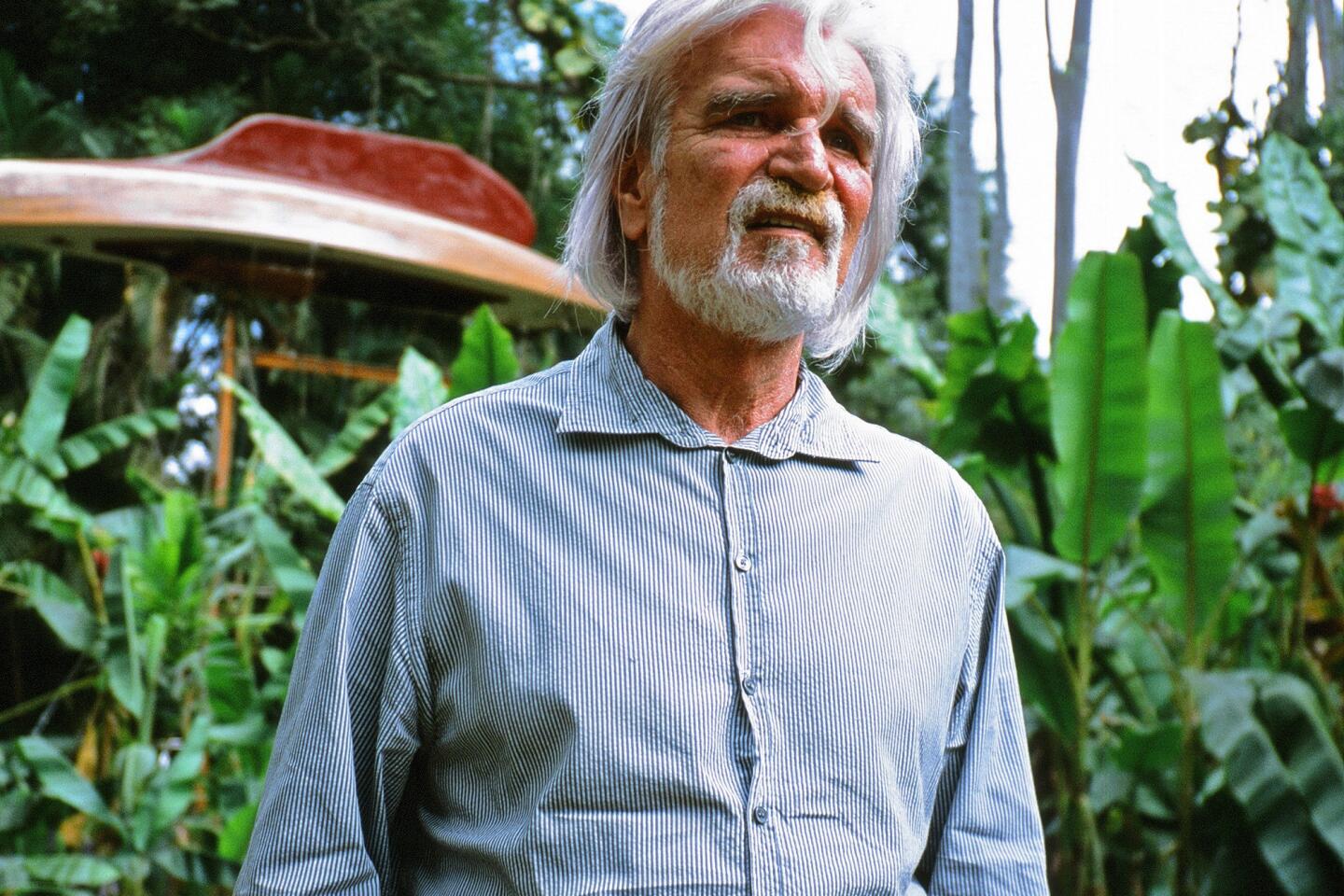

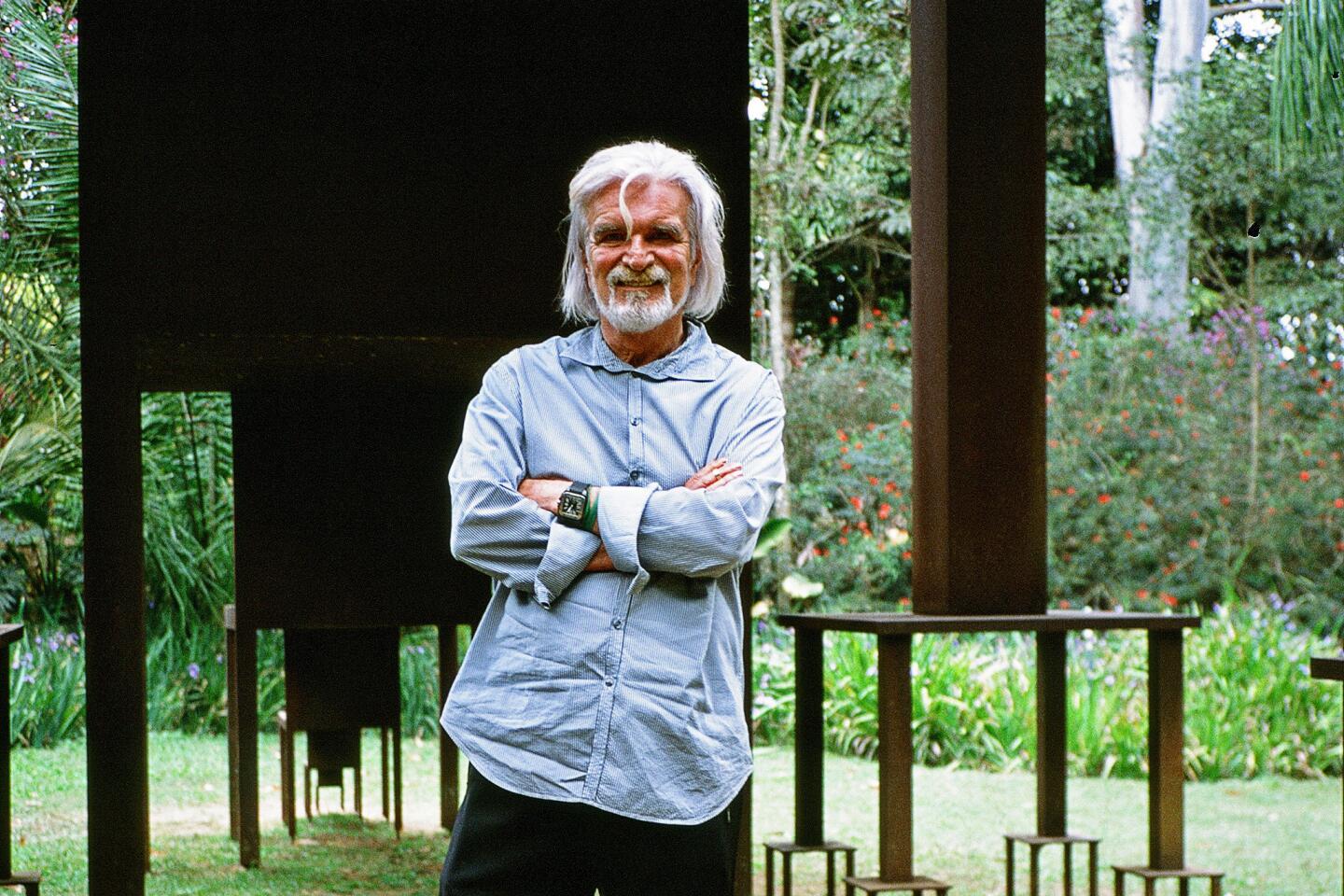

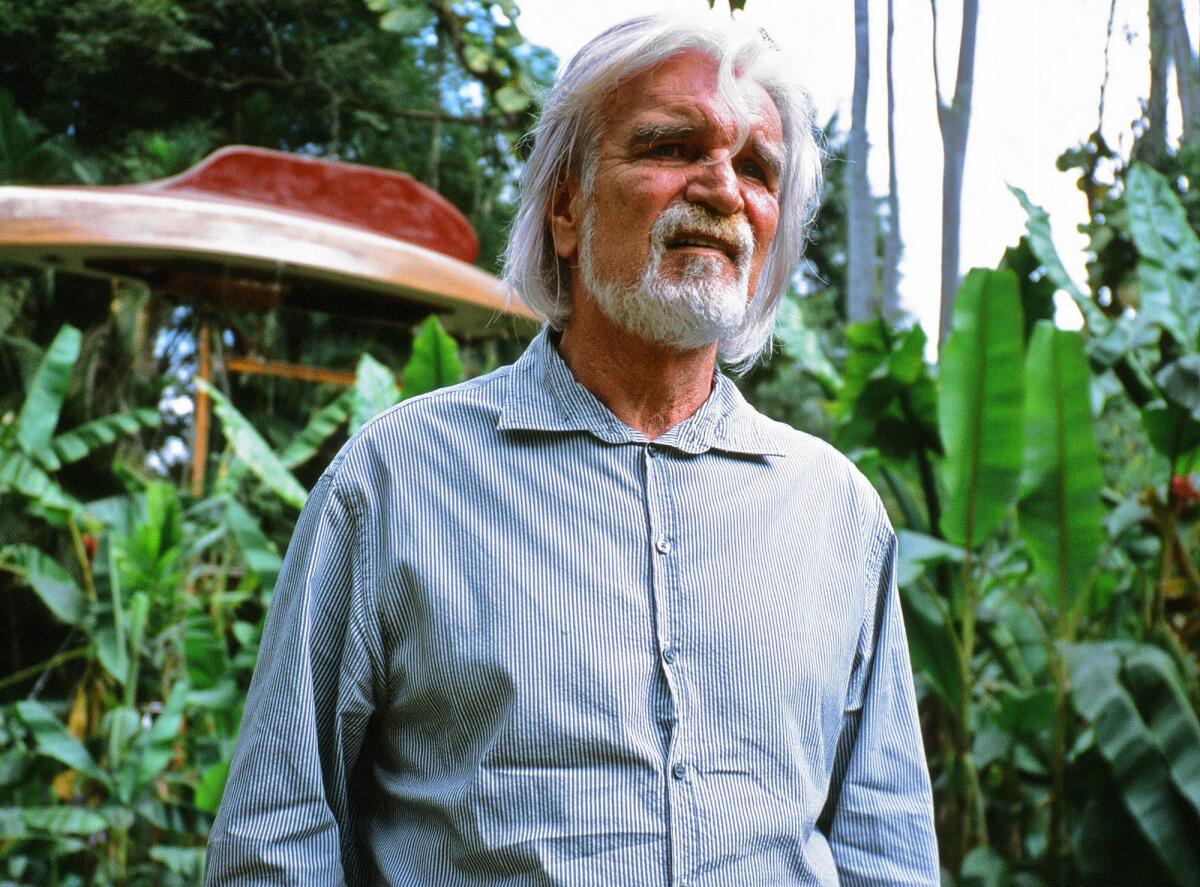

Reporting from BRUMADINHO, BRAZIL — His hands in constant motion, twiddling alternately with a cigarette, a metal hair clip and the straw for his coconut water, the mining millionaire some call Brazil’s Willy Wonka walks through a tropical forest to a tiny geodesic dome guarded by a smiling girl.

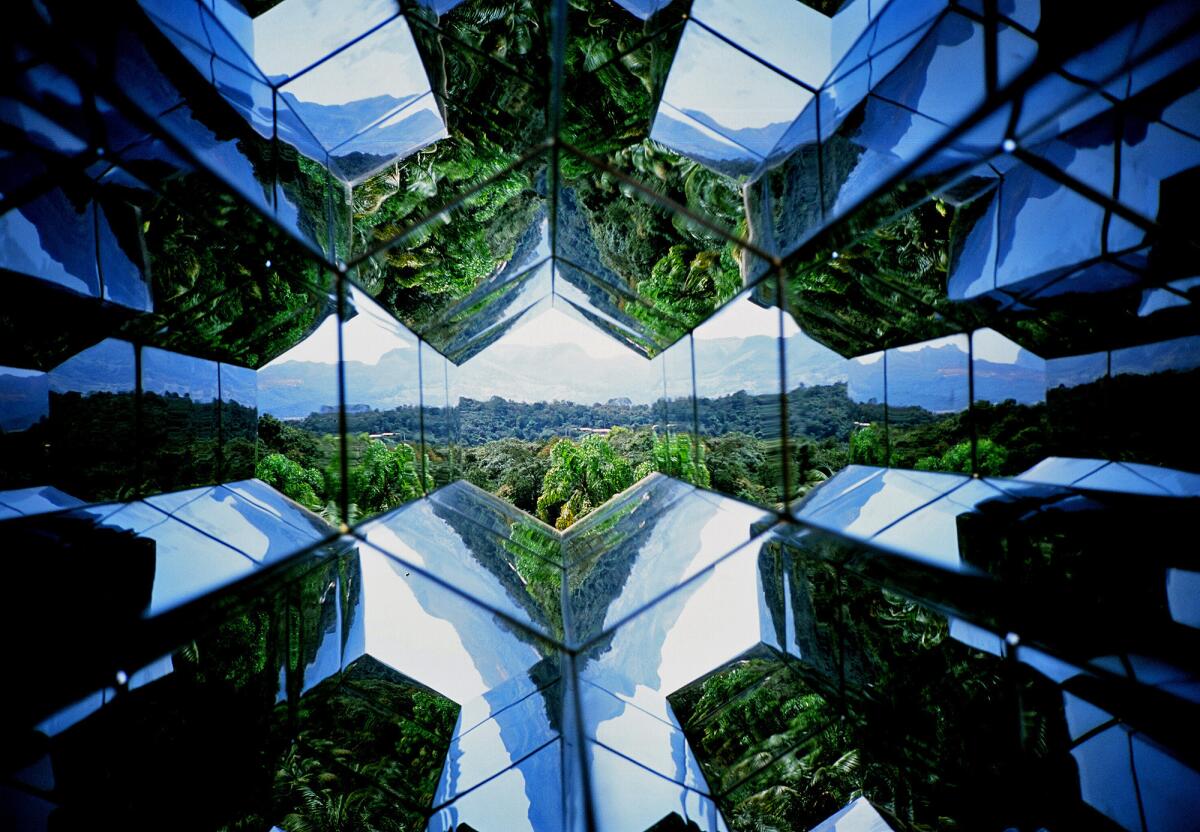

She guides visitors inside, where senses are assaulted by brilliant lights flashing at shifting speeds as a tiny column of water rises and falls. It’s a permanent installation by an Icelandic artist here at what may be the world’s largest open-air modern art museum.

Bernardo Paz likes to call his 5,000-acre creation, named Inhotim, a transformative place.

“When you enter this dream, you are transformed, and you start to imagine the life you’d really like you have,” he says. “You don’t want to go back to your life in the city and you can’t leave here.”

Paz has won admiration from lovers of art and nature alike for his fantastically reworked utopian landmass, even if he sometimes leaves others bemused by the grandiose goals he has for the project, which he says will last 1,000 years.

Inhotim, he says, will help the young and poor of the world imagine and prepare for “post-contemporary society.”

“We will have 15 to 20 years of revolts and much violence, since those who were never informed are now being informed, on the Internet. The poor are learning about the lives of the rich,” he says, wearing Louis Vuitton slippers and mud-caked athletic trousers.

He adds that the wave of protests that took hold of Brazil in June are just the beginning of a long and painful process. The Vatican, for example, will fall. “We will have a period of fatigue, and finally, a process of maturation.”

Although Paz, 63, has poured “at least hundreds of millions” of his dollars into creating Inhotim, he insists that he is not rich, he is not powerful, and that the stunning works tucked among even more stunning landscapes here are not a “collection.”

He says that the era of rich men is coming to an end, as he uses his vast mining fortune to reshape rural Brazil and inspire people with his own, sometimes less than humble, visions.

His bright blue eyes darken when asked about his various nicknames, such as “the emperor” of Brumadinho, the small city he has transformed here.

The same goes for the Wonka comparison -- “Do you see any chocolate here?” -- but Paz is quite comfortable comparing himself to another curator of fantasy.

“There is no paradigm in the world for anything like Inhotim. But there is one comparison that can be made,” he says. “We are building the Disney of the future. The Disney World of culture, the intellect, the environment, and research.”

Inhotim is in the state of Minas Gerais, which means General Mines, referring to the sites where the gold and iron ore below the surface was extracted to fuel a boom more than three centuries ago, and a more recent one over the last decades.

That’s how Paz got rich, as China’s demand for steel pushed up the price of iron ore. As luck would have it, he controls iron ore mines after taking over some businesses from the father of the first of his wives. (He is now with his sixth, a 31-year-old designer, who lives in Sao Paulo, a city he “detests.”)

Money poured into his pockets almost accidentally as Brazil went through a boom that won’t be repeated soon, he says.

Inhotim gave him something to do with the cash.

Much of the art on his compound comes from famous contemporary artists whose highly regarded and deeply intellectual works fill even the most blase and well-traveled art experts with astonished glee. But for many in the crowds that spend a day or two ambling over the grounds, the real treat is the sculptured natural beauty of the botanical gardens.

Paz -- whose involvement with contemporary art was accelerated by his marriage to successful Brazilian artist Adriana Varejao, which ended in 2005 -- prefers the gardens. But his mind today is focused on something else: getting the planet ready for the future.

He says he will soon bring together “the world’s 10 greatest thinkers” -- he can’t remember who they are at the moment, except that Bill Clinton isn’t one of them -- to write the “Carta Inhotim,” to outline a set of principles for the future world.

If he has his way, that future world will bring down what he calls rampant free-market capitalism that has created “financial monsters” who helped ruin continents and destroy the global middle class. He is more than happy to watch them fall.

He’s keenly aware that an extremely expensive dream park might not continue as he wishes after he dies, so he’s in a mad rush to construct a set of hotels, restaurants and other paid-for adult amusements to help make Inhotim viable financially.

“I’ve done this all with my own money, because I need to have more muscle, to control what’s happening,” says Paz, leaning against one of the carts on his ranch, in front of the entrance to the botanical scientific research center at Inhotim. “When the investors get involved it becomes all about short-term profit.”

According to local legend, the name Inhotim probably came from “Mr. Tim,” after the property’s former owner. Originally a private tract of land for Paz’s own enjoyment, it has been open to the public for more than a decade.

Last year, Paz’s 1,200 employees welcomed more than 300,000 visitors, who pay about $10 (with free admission one day each week).

“You understand here how easy it is to mold the world into a world of beauty, and beauty is fundamental for us,” says Paz, something of a sight himself, who accepts with laughter that dye has left his shoulder-length hair white and blue.

The project began when Brazilian contemporary artist Tunga persuaded Paz to start collecting contemporary art. Eventually, he allowed artists all the space and resources they needed to create larger-than-life works.

Paz now owns more than 500 works of art, and 110 are on display, nestled among Inhotim’s verdant hills. Some jump out from their surroundings at visitors, while others blend in.

What looks from afar like a set of charred tree trunks is actually “Beam Drop,” by Chris Burden, a work created by dropping giant construction beams into a pool of concrete and letting them set. On the top of a hill (one can hike up, or take a golf cart) is Doug Aitken’s “Sonic Pavilion,” within which visitors can hear the sounds of Earth emanating from a hole bored hundreds of feet below the surface.

And there are indoor galleries, such as the one housing avant-garde hero Helio Oiticica’s “Cosmococa,” a dark exploration of, among other things, drugs, counterculture, Marilyn Monroe, Jimi Hendrix and John Cage.

American artist Matthew Barney’s striking “From Mud, a Blade” takes on special significance.

The installation is inspired by a narrative in the African-inspired Candomble religion in which the god of iron, war and technology takes on the spirit of forests, plants and nature. A giant dirt-red tractor housed in a steel-and-glass dome appears to have just ripped a lily-white tree out of the ground. The color contrast between machine and nature is initially clear, but the blade is also white, and the viewer realizes that even the tractor is made of things that were ripped out of the earth.

Paz volunteers that some people think Inhotim was paid for with more than just the proceeds of what his mines ripped from the ground, but he dismisses local media accusations of money laundering as the jealous fantasies of those who can’t comprehend what he’s achieved.

He says his money and influence are nothing compared with the real rich, who have throughout history used the rest of the world.

“Europe destroyed Africa, stole its wealth, brought it back home, then shut the doors for Africans,” says Paz, who says race and class disappear at Inhotim. “If Europe had left one Inhotim in each African country,” he says, that would have been a seed for a new society there.

Another cart rolls down the hill, where, just a few feet away, is a work of art that is also a functioning swimming pool in which-- for as long as Paz is around, at least -- everyone is free to take a swim.

Bevins is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.