Former reality TV star’s campaign shows: There’s a downside and an upside to running against Vladimir Putin

- Share via

Thousands of protesters had been standing in the cold for almost an hour by the time Ksenia Sobchak climbed up onto the truck’s open bed with a bullhorn.

The protesters were demanding the closure of a massive trash dump, some 60 miles northwest of Moscow, that people living in the region claim is causing respiratory problems and skin rashes in children. “I’ve been here for only 20 minutes and my head already hurts,” Sobchak shouted as television news crews pointed their lenses at her. “We don’t need a government that doesn’t value our health!”

Sobchak, 36, is running for president in Sunday’s election, and has cast herself as a protest candidate representing Russians who are fed up with President Vladimir Putin’s 18 years of autocratic rule. Once better known as a socialite with family ties to the Kremlin leader, Sobchak has split the opposition with her surprise decision to run for president. Many Putin opponents see her run as a betrayal of Russia’s most recognizable opposition leader, Alexei Navalny, who is barred from running.

Others claim her candidacy is a Kremlin-approved project meant to kick some enthusiasm into an election with a foregone conclusion. With 80% approval ratings, Putin is assured of another six-year term.

Sobchak denies she is a Kremlin puppet, but admits she uses her ability to get on state television to her campaign’s advantage.

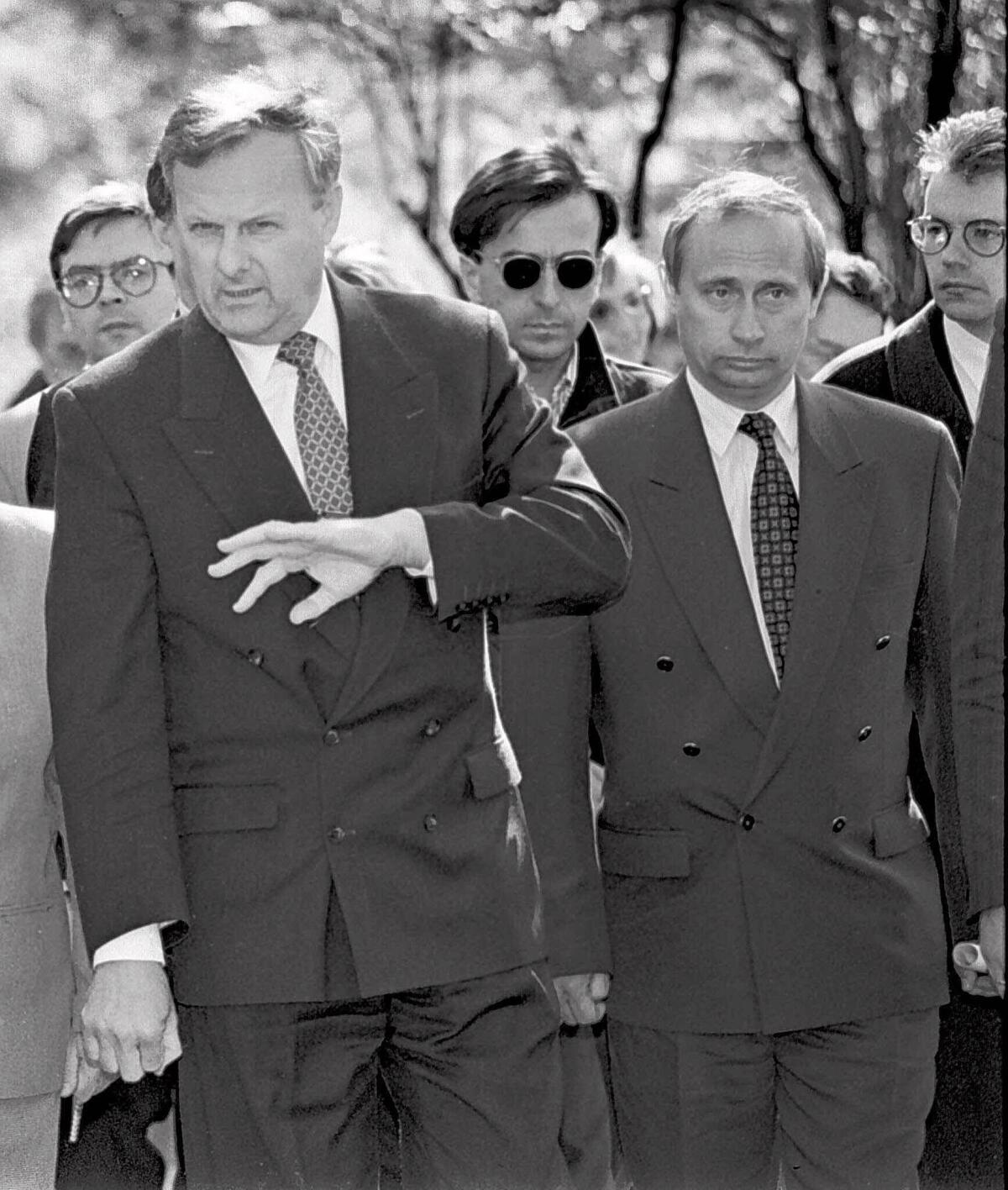

Sobchak is the daughter of Anatoly Sobchak, the first democratically elected mayor of St. Petersburg after the breakup of the Soviet Union and the political mentor of a young Vladimir Putin. Her mother is now a senator in the Federation Council, Russia’s upper house of parliament.

Sobchak’s family position in post-Soviet politics put her in the spotlight from a young age. As a young adult in the early 2000s, she became one of Russia’s most recognizable faces as a trend-setting “it girl” who frequently appeared on magazine covers and at one point hosted a reality television show. That phase coincided with Putin’s first tenure as president, when he presided over high oil profits and a growing class of wealthy Russians.

In 2011, Sobchak took a surprise turn and went from party girl to protester, joining tens of thousands of Russians demonstrating against what they claimed was a fraudulent presidential election in which Putin claimed a third term. She then became a journalist on one of Russia’s leading independent stations, TV Rain.

Criticism aside, Sobchak has managed to make her mark on Russia’s predictable election cycle by doing something no other opposition candidate has managed to do: talk about liberal subjects on state-run television and bring attention to issues being ignored by the Kremlin.

She has said the 2014 annexation of Crimea, which had been part of Ukraine, was illegal. She has called for the legalization of marijuana. She supported equal rights for the LGBTQ community in a country notorious for passing a law that criminalized gay “propaganda.”

She has even tried — and failed — to get Putin’s campaign disqualified.

“Some liberal-oriented people are ready to vote for her because they say it doesn't matter who is talking about liberal values, it's just important that these values are on television and reaching a broader space than just the internet,” said Andrei Kolesnikov, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Moscow Center. “If she's the only legal liberal to stay in politics, why not try? Navalny will not be allowed forever to be in the legal politics.”

Navalny, who has managed to gather an unprecedented following of young and middle-class supporters for his anti-corruption campaigns, is banned from running for president because of a 2013 fraud charge that he says was politically motivated.

While Sobchak has said a vote for her is a protest vote against Putin, Navalny has called for a boycott of the election to show the Kremlin it lacks legitimacy without a non-Kremlin-backed challenger on the ballot.

Sobchak’s celebrity status means national television crews follow her. That was the whole point for the demonstrators gathered in Volokolamsk, a Moscow suburb about 60 miles from the city center, to demand closure of the dump in adjacent Yadrovo.

Last year during a televised call-in show with Putin, residents from Kochino, another Moscow suburb, complained to the Russian president via video call about a similar dump in their region that they said was causing health problems. The day after the three-hour call-in show, Putin instructed local authorities to close the dump.

The Volokolamsk residents hoped that Sobchak’s presence would have the same effect.

After her brief remarks atop the truck bed, Sobchak jumped down and led a group of protesters to the dump’s entrance gate. With the press in tow, she banged on the metal gate and demanded to be let inside. Riot police stood on the other side. Sobchak stood her ground until, eventually, the dump’s director let her in.

“I didn’t come here to see Sobchak,” said one of the demonstrators, Anastasia Tikhomirova, 36, as she shuffled back and forth in the cold. “But if she’s bringing the media with her, then great. We want the media to cover the situation as much as possible so [Putin] will see the problem and close the dump!”

Still, Tikhomirova said she wasn’t planning to vote for Sobchak.

“I don’t see any real candidates on the ballot,” she said. “You see what’s going on here? No one hears us. That’s why I’m not going to vote.”

Everyone, including Sobchak, knows she won’t win. Sobchak is polling in the single digits, as are the other six candidates running against the 65-year-old Russian president.

In addition, Sobchak is facing the challenge of high negative ratings. Eighty-two percent of respondents in a recent poll by the Russian Public Opinion Research Center expressed negative views of her, higher than for any other candidate.

She is seen by many as tainted both by her history as the former host of a reality TV show — Russians have less tolerance for that than Americans, apparently — and by her onetime image as a privileged rich girl.

“And worse, she's from the family of Sobchak, who was an ally of [former Russian President Boris] Yeltsin and he is seen as the man who disrupted the country,” Kolesnikov said.

With no doubt that she will lose on Sunday, Sobchak on Thursday launched the Party of Change with fellow opposition politician Dmitry Gudkov, indicating a political agenda that extends beyond this election. Sobchak said her party would focus on Russia’s parliamentary elections in 2021.

“I think it's a tough job to get real political change in Russia, and different people have different visions of how to do it,” said Olga Oliker, the director of the Russia and Eurasia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a think tank in Washington. “Still, nothing is impossible.”

Sobchak is trying “to show that she is not Navalny because she's about participation, not protesting,” Oliker said.

On the nightly news after the protest against the trash dump in Volokolamsk, some demonstrators were disappointed that their fight only got 30 seconds of coverage.

But Maria Isayeva, 53, said the event changed her mind about Sobchak.

“No one else has come to support us here, and we’ve had several protests to try and get the dump closed,” she said. “Sobchak is the only one who has supported us. I will vote for her.”

Twitter: @sabraayres

Ayres is a special correspondent.

ALSO:

Following ex-spy's poisoning, Brits are on edge about nerve agents. They should be

Laughing? Not so much. Most Russians just wish the election-tampering story would go away

Russia's shadowy world of military contractors: independent mercenaries, or working for the Kremlin?

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.