Caught between two rivals, ethnic Hungarians in Ukraine walk a fine line

- Share via

Reporting from UZHHOROD, Ukraine — In early October, Andriy Minchuk found himself blacklisted, right alongside Ukraine’s enemies.

His personal information was leaked online by Peacemaker, a publication that boasts ties to the Ukrainian security services. It posts personal information about the “Kremlin’s agents,” including separatists in southeastern Ukraine and turncoat officials and servicemen in Russia-annexed Crimea.

This was no small matter. A pro-Russia publicist and a former lawmaker were shot dead in April 2015, days after Peacemaker disclosed their addresses. Other blacklisted people have faced threats, harassment and travel bans.

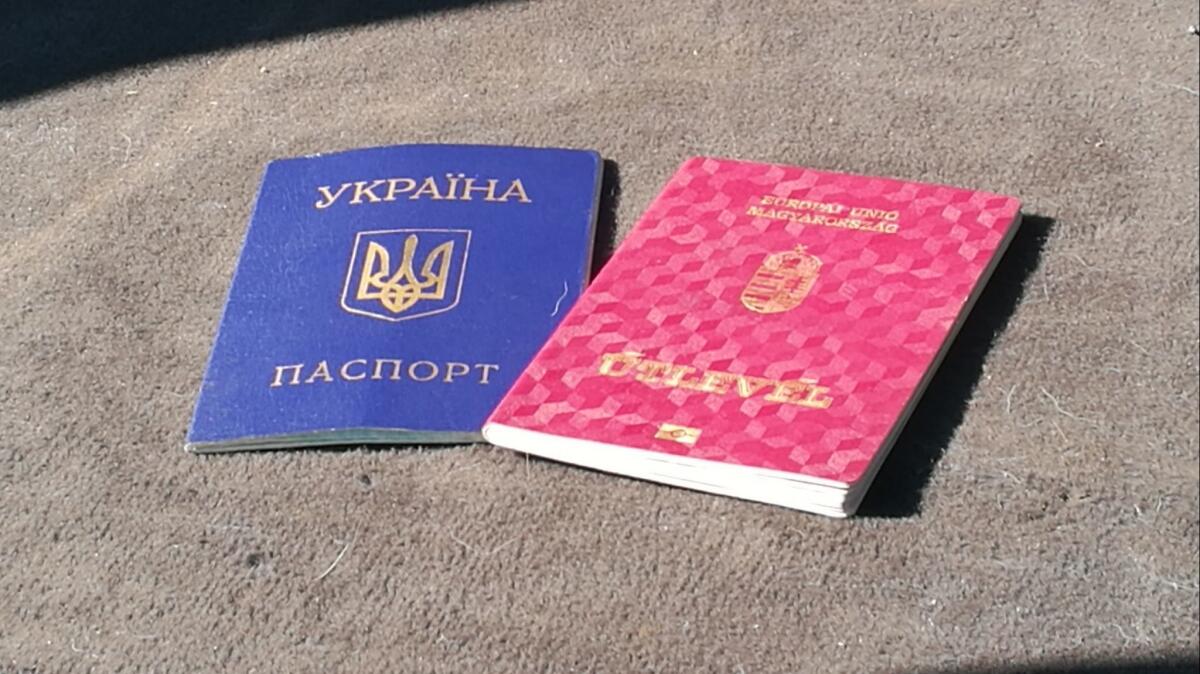

But Minchuk, who lives in Transcarpathia, an impoverished western region of Ukraine, insists that he did nothing to warrant inclusion on the list. His transgression, it appears, was being one of some 100,000 ethnic Hungarians in Ukraine who hold Hungarian passports.

Peacemaker published his personal information, including the number on his Hungarian passport, in a list of some 500 public servants and state employees who had obtained Hungarian citizenship – making them “separatists” and “traitors.”

But Minchuk denied ever holding a government job – let alone fomenting separatist views. He said the leak could harm him, his wife and their 3-year-old son.

“I’m an average guy, I work hard, I pay my taxes,” the 33-year-old IT expert said in an interview. “This is very bad for me and my family.”

Although Ukraine prohibits dual citizenship, the only punishment is a minuscule fine. Yet, the blacklisting threw Minchuk into a political maelstrom that imperils Ukraine’s pro-Western course, tests its commitment to multiculturalism and plays into the hands of its archenemy, Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Viktor Orban, Hungary’s far-right and Euroskeptic leader who said that Putin “has made his nation great again,” is Moscow’s staunchest ally in the European Union.

Orban also champions the “integration” of the 2 million-plus Hungarian diaspora that remained in Slovakia, Romania, Serbia and Ukraine after a 1920, post-World War I treaty deprived Hungary of two-thirds of its territory.

Since 2011, Orban’s government has issued more than a million passports to diaspora Hungarians. They, in turn, were allowed to vote in Hungary’s elections — and most supported Orban’s Fidesz party.

Orban has long urged Ukraine to give autonomy to Transcarpathian Hungarians. There are about 150,000 ethnic Hungarians in Transcarpathia, or about one-eighth of the region’s population.

“They must be granted dual citizenship, must enjoy all of the community rights and must be granted the opportunity for autonomy,” he said in 2014, days before pro-Russia separatists in southeastern Ukraine agreed to secede and unleashed a war that killed thousands.

Weeks earlier, Russia annexed Crimea, which had been part of Ukraine, after violent protests toppled Kiev’s pro-Russia President Viktor Yanukovich. Citing oppression of ethnic Russians, Moscow demanded that Ukraine become a decentralized, federal state with broader rights for minorities.

Orban’s demands echoed Putin’s – perhaps not surprising, since their interests in Ukraine largely coincided.

“The steps of the Hungarian government seem to be promoting Russia’s foreign policy interests more than those of Hungary,” Peter Kreko, director of the Political Capital Institute, a Budapest think tank, said in an interview. “These steps don’t help ethnic Hungarians in Transcarpathia, they isolate Hungary within [Europe] and help Russia hamper Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic integration.”

Meanwhile, under its new president, Petro Poroshenko, Ukraine passed a law that limits education in minority languages. Intended to curb the use of Russian, the law affected other minorities – Hungarians, Romanians, Poles and Ruthenians – who see education in native languages as a pillar of preserving their identity.

Orban’s government funds Hungarian-language schools in Transcarpathia, and it threatened to block Ukraine’s push to join the European Union and NATO if Ukraine did not withdraw the legislation.

The EU and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization reprimanded Kiev for violating minority rights, but 11 NATO member states concluded that Orban’s ultimatum puts “the strategic interests of the alliance in jeopardy.”

In response, Ukrainian nationalists marched with torches to the Hungarian Consulate in Berehove, a border town known as Ukraine’s “Little Hungary.” A Hungarian culture center was firebombed twice, and the faces of its members appeared on billboards signed, “Let’s stop separatists.” Ukraine said the bombers were Polish far-right nationalists with ties to Russia.

Poroshenko complained, without providing evidence, that the region “has become an object of attack of Russian intelligence services to complicate our nation’s relations with Western partners.”

One of his ministers deplored the weakness of Poroshenko’s policies in Transcarpathia and compared the region to annexed Crimea and the separatist Donbas region, which is under the control of pro-Russia rebels.

“Transcarpathia has not been lost yet, but I absolutely agree that we’re losing territories where the central government has no policies,” said Heorhiy Tuka, who is the Ukrainian minister for territories that include Crimea and the Donbas, in televised remarks.

Tuka helped found the Peacemaker website in 2014.

In September, a video surfaced online showing ethnic Hungarians receiving passports at the Berehove consulate as diplomats offer them Champagne and urge them to keep their new citizenship secret from Ukrainian authorities.

Prosecutors said they would investigate the distribution of passports as “high treason,” and Kiev pledged to build a military base in Transcarpathia in an apparent step to counter a hypothetical military threat from Hungary.

Ukraine’s main security agency, SBU, began investigating a Budapest-funded charity that spent tens of millions in Transcarpathia on infrastructure projects such as construction of schools, roads and hospitals for “separatism.”

Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto accused Ukraine of starting a “state-assisted hate campaign,” and in early October, Hungary blocked the annual meeting of the NATO-Ukraine Joint Commission, which works toward including Kiev in the bloc. It was the second time Hungary had done so.

Then the Peacemaker blacklist brought the conflict to a boil.

For many Transcarpathian Hungarians, their burgundy-red passports are not political statements but open tickets to work and study in the EU.

“There is no future in Ukraine,” said Olga Nemesz, whose husband works in Germany while she raises their two children in Berehove. “It’s really hard to survive here.”

After the blacklisting, several public officials and state employees quit their jobs. Minchuk’s family has not been affected, but has a simple solution if things go wrong.

“If there is a danger for my family, we will go to Hungary,” he said.

Mirovalev is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.