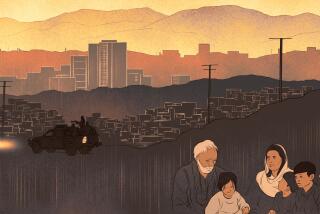

Great Read: From U.S. ally to prison to redemption in Afghanistan

Temour Ebrahim at his home in Ghazni, Afghanistan, in November.

- Share via

Reporting from Ghazni, Afghanistan — Temour Ebrahim had little reason to be nervous when U.S. soldiers summoned him to their base in this edgy highway town 80 miles south of Kabul, the Afghan capital.

For the better part of a decade, he had been coming to the garrison in Ghazni, weaving through a dusty maze of Hesco barriers for meetings with U.S. military and civilian personnel.

Tall and thickset, with an English accent from living two decades in London, Temour was well known to the Americans as a former police commander, liaison to ethnic Hazara militias and source who helped locate Taliban weapons.

But when he arrived that afternoon in December 2011, an Army Special Forces team arrested him. They accused him of working with the Taliban and spying for Iranian intelligence, bound his wrists with plastic handcuffs and shoved him into a cold cargo container in a restricted area of the base.

This is a joke, Temour recalled thinking. He denied the allegations.

A week later he was transferred by helicopter to the U.S. prison at Bagram airfield. He would spend the next 2 1/2 years in detention — a dramatic reversal for a man who once was the closest thing the United States had to a friend in this shadowy corner of Afghanistan.

Despite their working together, the Americans had remained wary of Temour — and he learned the hard way that he could not trust them.

His is a murky tale of alliance, betrayal and, ultimately, redemption that traces the arc of the United States’ longest war.

::

The Americans who invaded Afghanistan in 2001 found an insular society hardened by Soviet occupation, civil war and Taliban rule. Into this land of gaunt, inscrutable faces came Temour, with his round belly, Bob Marley tunes on the car stereo, and fluent, lilting English that to U.S. forces must have sounded like its own kind of music.

His family, members of the Hazara minority, had moved to London when he was 9 after his father, who was active in opposition politics, learned he was being targeted by Afghanistan’s communist government. Temour returned to Afghanistan in 2001 at the urging of his uncle, a militia leader who helped U.S.-led forces oust the Taliban. Temour quickly became an asset to American troops working on reconstruction and counter-terrorism programs in Ghazni.

When U.S. commanders wanted to construct a school or well in a Hazara area, they called Temour. As the U.S. began to assemble a national army and police force, Temour helped get scores of his uncle’s fighters to hand in their weapons.

“The Americans back then were serious about building a new Afghanistan,” Temour said, “and a lot of us were on board with that.”

With an extensive network of contacts — including Afghan soldiers and police, Hazara militiamen, Taliban informants and village elders who opposed the insurgents — Temour also began supplying information about Taliban weapons hidden in the mountains.

“He was amazingly helpful in tracking down munitions,” said Brig. Gen. Blake C. Ortner, a Virginia National Guardsman who led U.S. forces in Ghazni from 2004 to 2005. “He did a lot of great things for us.”

Over the years, Temour collected thousands of dollars in rewards for tips that led to weapons busts or arrests of Taliban suspects, according to officials who worked with him. A large cache of 107-millimeter rockets — a favorite among insurgents — could net as much as $2,500.

Many Afghan warlords became rich off American cash, but Temour said he gave most of the money to sources who otherwise would have sold their information to drug syndicates, the insurgency or other groups opposing U.S. interests. He could afford a Toyota truck and some jewelry for his wife, but they remained with their three children in a modest pink house along a dirt road in Ghazni.

“In Afghanistan, we’ve got to pay people to get things done,” he said. “I was paying people out of my pocket for the information I gave to the Americans.”

His interests were not only financial. Many Taliban regard the Hazaras, who are Shiite Muslims, as infidels, and had slaughtered thousands.

“There were times when I felt he was kind of using the shield of U.S. forces to maybe get back at people,” said Ortner, who is now senior associate legislative director for the Paralyzed Veterans of America, an advocacy group.

“But he always came across to me as being very interested in what was best for Afghanistan.”

The charges against his old ally, he said, were hard to believe.

“I would not in a million years think he was playing both sides.”

::

In 2006, Temour briefly led a contingent of 70 Afghan police officers in the southern province of Zabol. Mark Wenell, an Air Force technical sergeant from Arizona who was training the Afghans, said Temour’s men “were some of the only people I could count on to save these villages when they came under attack by the Taliban.”

Afghan Hazaras have often been described as sympathetic to Shiite-led Iran. But Wenell, who retired from the military after 22 years, credited Temour with helping U.S. forces recover 39 Iranian-made antipersonnel mines in Zabol in early 2007 — one of the first significant caches of Iranian munitions found in Afghanistan.

Back in Ghazni, Temour established contact with an Army Special Forces team known as an Operational Detachment Alpha, which worked out of a secure compound on the base. The team’s dozen or so members rotated every few months, and in mid-2011, Temour got into a dispute with a new team leader, saying he hadn’t been paid for two weapons busts.

That September, the ODA team declined to pursue a lead Temour had, about a cache of Taliban munitions in the hilly badlands of Deh Yak. He took the information to another U.S. unit, which recovered about two dozen roadside bombs, according to emails reviewed by The Times.

Temour now believed he was owed well over $15,000. Military personnel told him that there was a funding shortfall and that the money would be available within weeks, according to a U.S. official with knowledge of the matter, who was not to be named because he wasn’t authorized to discuss it publicly.

Around the same time, the ODA team began telling other U.S. personnel of “solid evidence” that Temour was working with Iranian intelligence, said a U.S. official who requested anonymity to discuss private communications. Temour’s American contacts cut off communications with him.

On Dec. 26, he got a call from an unfamiliar voice telling him to come to the base the next day to “settle accounts.” There, he was arrested. Among the items taken from him were his cellphone and a notebook containing the numbers of all his American contacts.

::

He would spend nearly 18 months at Bagram, the prison often described as a “second Guantanamo,” before being transferred to Afghan custody.

In two hearings in 2013 at the Justice Center in Parwan, an Afghan court for national security cases that was created with heavy U.S. support, Afghan prosecutors argued that Temour was “a spy and agent of the Iranian government” and had supplied information to the Taliban. They offered as proof statements by coalition forces and Afghan intelligence officials, according to court records.

The Pentagon administered two polygraph exams to Temour at Bagram. If either yielded anything to incriminate him, it did not surface at trial.

Prosecutors presented a list of weapons U.S. forces said they seized from Temour’s home, including a handgun, ammunition, a silencer, GPS equipment, Afghan army and police uniforms and, most damningly, a suicide vest.

Through a lawyer assigned to his case a week before the hearing, Temour denied possessing the vest. He said the other items were given to him during his decade of work alongside Afghan and U.S. forces.

“The prosecutor has not been able to connect Temour with any terrorist organization,” the Legal Aid Organization of Afghanistan, a nongovernmental group that helped in his defense, wrote in a letter to The Times this year.

The judges agreed, saying the terrorism and espionage allegations were unsubstantiated, but sentenced him to 18 months for possessing illegal weapons. Three months later, with little explanation, an appellate panel extended his term to five years.

In June 2013, he was moved to the giant Afghan army detention center at Pul-e-Charkhi, east of Kabul, where he shared a cell with five other prisoners. In a brief interview there in April last year, a handcuffed Temour, wearing a scruffy prison beard, said through a wire grate in the visiting room: “Is this how America treats its friends?”

::

As the United States sought to wind down the war, it gradually handed control of Bagram prison and its thousands of detainees to the Afghan government. Afghanistan has released the vast majority of prisoners, citing a lack of evidence.

Last July, Temour was set free after a review board appointed by then-President Hamid Karzai determined there was no evidence to support his continued detention.

“He was not armed when detained, there’s no evidence to show he was spying for foreigners, he wasn’t dealing drugs — anything,” said Abdul Shakoor Dadras, the head of the panel.

Temour, now 45, returned to Ghazni and spent several unhappy months without a job. Worried that security in the province was deteriorating — and itching to get back in the game — he emailed a former U.S. contact.

“One man, what he did to me, it does not mean I should blame everyone in the United States Army or military,” he wrote.

The contact suggested a meeting at Bagram, but Temour demurred, fearing another setup. The American did not write back.

Then in February, Mohammad Mohaqiq, deputy to the chief executive in Afghanistan’s unity government and the country’s most prominent Hazara politician, hired Temour as an advisor on security affairs. In one of his first official duties, Temour arranged a meeting between Mohaqiq and Maj. Gen. Scott Berrier, deputy chief of staff in charge of intelligence for the U.S.-led military coalition.

A little more than three years after his arrest, Temour arrived for the meeting clean-shaven and wearing a double-breasted blazer over his Afghan shalwar kameez. In a picture, he stands stiffly next to Berrier, who is holding a small vase, a gift from Mohaqiq.

Since then, Temour has met often with U.S. military and civilian personnel in Kabul to discuss security issues. At first, none mentioned his time in prison. Perhaps they were embarrassed about what happened to him, he thought.

But eventually he was asked to take another polygraph. More than ever, he felt he had nothing to hide. When he passed, he got what he had been waiting to hear for years: an apology.

“They’re all shocked that I would come back and help the U.S. after what they did to me. And I said, ‘What am I going to do, go and sit with the Taliban?’ I’m a Hazara. I’m a Shiite Muslim,” Temour said. “What they accused me of never made sense.”

One thing he gained from prison, he said, was time to study the Koran.

“I hadn’t really read it closely before. I realized that one of the main things it teaches is forgiveness.”

Twitter: @SBengali

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.