Operatic trills rise from Botswana bush

- Share via

Reporting from Gabarone, Botswana — The villages of Botswana are full of music. Gospel music. Choral music. The singsong repetitive music of rote classroom learning.

But not opera, until now.

As a small girl in the village of Ramotswa, Tshenolo Segokgo learned to sing in a church choir. She grew up and moved to the capital, Gabarone, for vocal lessons.

Then one day in 2004, her music teacher put on an opera CD.

“It felt like it was angels singing,” she recalls.

::

Five years later, on a purple African night, operatic strains rise from a white, corrugated-iron shed in the bush.

Clouds gather and darken. Lightning dissects the sky. Rain slashes down, beating on the shed’s tin roof.

Inside, the sounds get louder. It’s just a rehearsal, but Segokgo and the other singers of Botswana’s first opera house, a converted garage, hold their own against the weather as they perform the first opera ever set in Botswana.

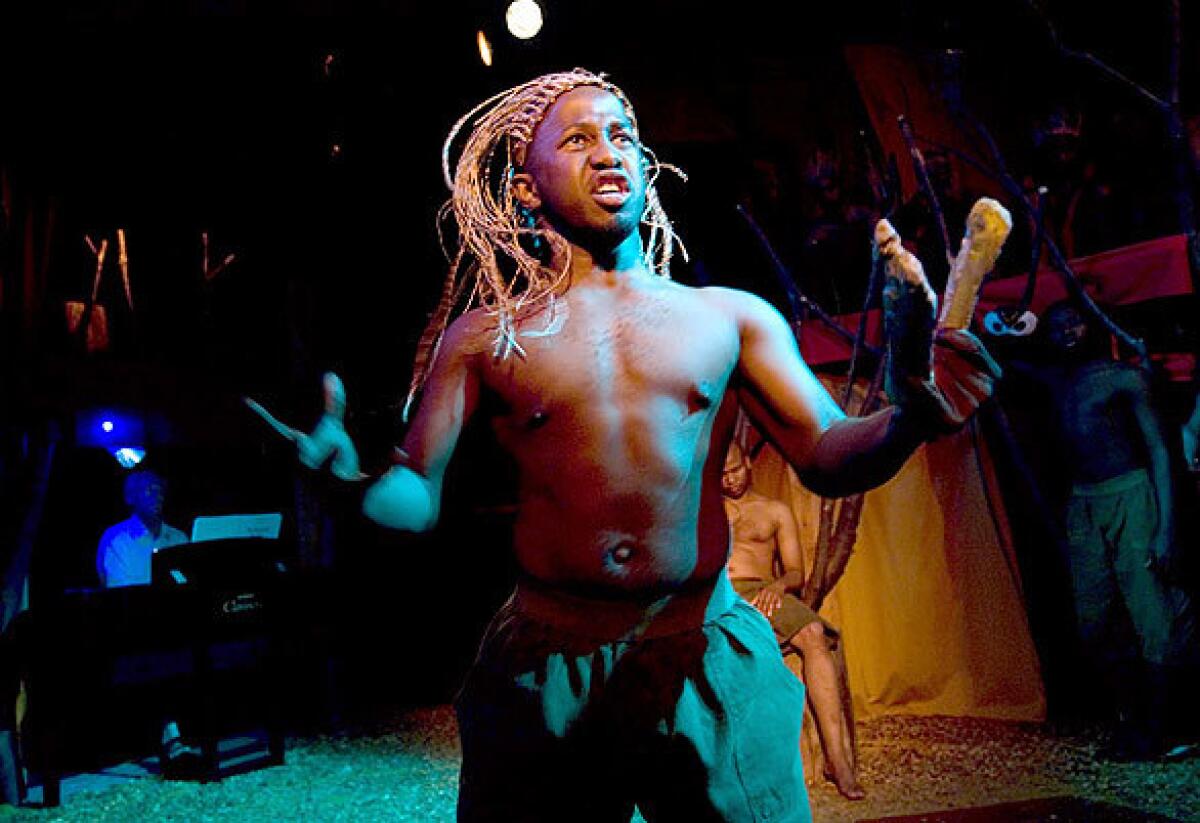

A tale of evil, betrayal and lust unfolds: “The Okavango Macbeth,” the story of a troop of baboons and its alpha female, Lady Macbeth, who stirs up trouble, plotting murder.

Segokgo, as Lady Macbeth, struts the stage, her voice rising in sweet soprano, but the words shriek death. “Kill him now!” she sings, urging her mate to dispatch the alpha male baboon. “Kill him now!” Her costume, simple black clothing and a headdress, is as far from the plush velvet costumes of traditional opera as the tin shed is from the Met.

“It’s a challenging role,” she says later, “because I haven’t done that kind of role before. The real challenge is that I’m a baboon that loves power. The thing is walking like a baboon and trying to pose as a baboon.”

When Segokgo began her singing lessons, it was clear she possessed talent and passion. But music, she figured, was no career.

“I didn’t think it was something serious. I was just singing for pleasure.”

Segokgo’s big break came just over two years ago, when a cultural attache from the French Embassy heard her perform. A scholarship was arranged. She was sent to study at the Bourg-la-Reine conservatory, outside Paris, for two years.

It was a big adjustment for a village girl.

“I didn’t speak French. It was a new environment. I had to adapt to the lifestyle of the French. But it changed my life.”

‘The Okavango Macbeth” was conceived by novelist Alexander McCall Smith, the Zimbabwean-born Scotsman famous for the “No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency” series of books, with their whimsical take on Botswana life. (Okavango is the name of a vast river delta that is one of Botswana’s most distinctive natural features.)

McCall Smith, an opera lover and amateur musician, wrote the libretto for the hourlong work. The score was composed by fellow Scotsman Tom Cunningham, a conductor and composer who had set some of McCall Smith’s poetry to music.

The opera, which had its premiere last month, was staged with a solo piano as the singers’ only accompaniment. There wasn’t room in the opera house, or money in the budget, for an orchestra. Still, McCall Smith said it was Botswana’s first “proper operatic production,” with paid singers.

“I don’t think that there has been anything like this before,” he said. “Indeed, I don’t think that there has been anything put on, apart from amateur Gilbert and Sullivan and the like.”

It’s not easy to find the opera house, along a winding, bushy track outside Gabarone, a neat but bland city full of shopping malls, manicured roundabouts and tall mirrored skyscrapers built for the bureaucracy. (The city, disappointingly, bears little resemblance to the Botswana of McCall Smith’s books, a quaint, soulful place of ramshackle buildings and good intentions.)

The building, part of a military recruiting station in the 1940s, caught the attention of a man named David Slater when it was put up for sale. Slater is a leading figure in Botswana’s tiny classical music scene, and Segokgo’s voice teacher. As it happens, he is also a friend of McCall Smith’s. “I had on previous occasions commissioned him to arrange concerts to coincide with my visits to Botswana,” the writer recalled.

The garage reminded Slater of Speedy Motors, the slightly rundown garage in the detective series, so he encouraged McCall Smith to come have a look. “He immediately said this should be an opera house,” Slater said.

An opera house? On a forgotten road outside Gabarone?

If Slater had any doubts, McCall Smith’s passion for opera swept him along. He and the novelist renovated the garage and dubbed it the No 1. Ladies’ Opera House. McCall Smith funded the project. Slater became musical director of “The Okavango Macbeth,” the venue’s first production.

McCall Smith said he has loved opera since his early 20s, when he saw his first performances in Rome.

Music has been important to him ever since, he said. McCall Smith plays bassoon (“badly”) in the Really Terrible Orchestra, an amateur ensemble which he co-founded that calls itself “the cream of Edinburgh’s musically disadvantaged.”

He recruited a childhood friend, Cape Town-based Nicholas Ellenbogen, to direct “The Okavango Macbeth.” Ellenbogen, a well-known playwright and director, founded Theatre for Africa, which set up dozens of small village theater companies across the continent in the 1990s.

“I used to be more famous than Sandy,” he says with a mock-rueful smile, referring to McCall Smith. They grew up as neighbors in the quaint town of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe.

Ellenbogen and his son Luke built the sets for the opera -- out of tree trunks, branches and bits of wood and wire -- to resemble a jungle where a group of baboon researchers sits in a hide-out observing the baboons.

They made the costumes too. Everything was done on a shoestring.

Staging an opera in what had been a shed posed problems. Ellenbogen had to bring lights and other equipment from South Africa. He struggled to find sopranos. He had to feed the cast at each rehearsal, and figure out how to get them back home each night because the opera house lies beyond the reach of public transportation. (He usually ended up driving some home, as far as 20 miles from the city.)

McCall Smith and Ellenbogen say they hope to find sponsors to take the opera abroad. The Scottish Opera and some festivals have expressed interest.

“I would dearly love it to get to an American audience, as I am sure that they would enjoy it. Ellenbogen’s production is stunning -- very physical and moving -- quite unlike anything I have ever seen before,” McCall Smith said.

As opening night approached last month, Ellenbogen worried that female cast members might quit at the last minute, as often happens in Africa, he says, when husbands or boyfriends suddenly exert control. Half the cast of 16 are women.

But most of all he worried about the performances. The singing was marvelous. But the acting . . .

After one run-through, a few evenings before the premiere, a frowning Ellenbogen scribbled notes on all the problems he saw.

“I don’t know how we’re going to get everything done in time,” he muttered to himself.

“Now come here, my loves,” he said, gathering the cast members and gently critiquing them, one by one.

“The murder scene needs to be a lot more dramatic,” he said. “And a lot louder. We need to work on that.”

Studying opera in France, Segokgo performed and participated in master classes across Europe. She would have stayed, but after receiving her diploma in June, her sponsorship ran out. There was no money for the master’s degree she hoped for.

She returned to Botswana, frustrated, but still nursing her dreams.

“It’s. . . . “ She hesitates. “I don’t know. I think it’s OK. I continue singing. And I’m giving some people singing lessons. So I am keeping that.”

Her voice trails off. Opera house or not, there’s not much opera in Botswana.

The “Macbeth” production was like a spell of rain after a drought.

But it was a two week-season, over all too soon. “I would love to go and continue studying and help other people develop their careers. I feel as if I am missing opportunities. Opportunities to continue my studying and singing abroad. I have to go away to succeed,” Segokgo said.

Onstage, she kept her disappointments hidden.

As Lady Macbeth, Segokgo stole the show. Her eyes popped with evil as her voice soared beneath the corrugated iron roof.

The audience laughed in the right places, and at the end they applauded for a long time. The ovation nourished her hope.

She’s waiting for her next break.

“I want to go really far,” she said. “I want to be a big singer overseas. That’s what I want to do.”

Dixon recently was on assignment in Botswana.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.