What it’s like to live in the world’s fastest growing major economy

- Share via

Reporting from Mumbai, India — Two sides to India’s growth story play out on opposite sides of a busy intersection in central Mumbai.

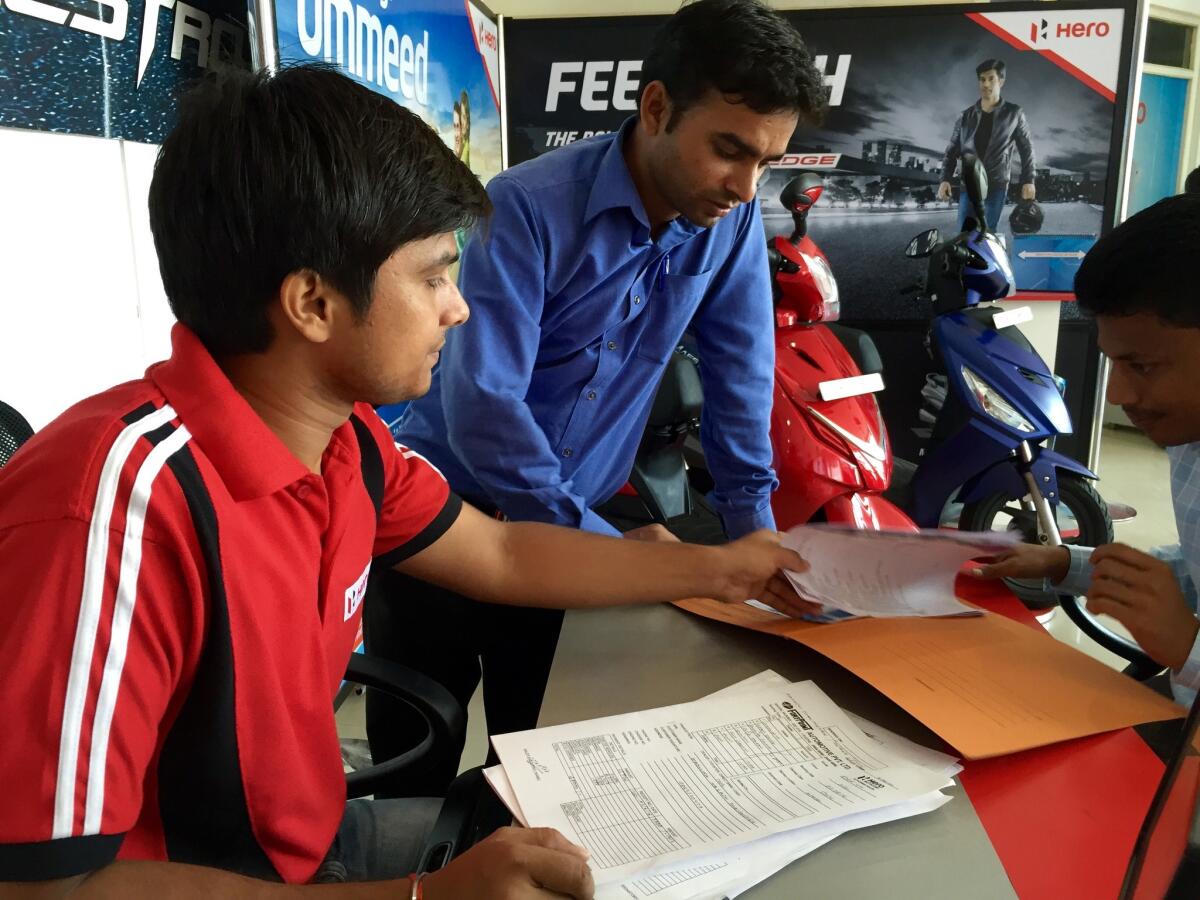

Inside a motorcycle showroom beneath posters of beaming, windswept riders, young salesmen in crisp polos run their hands over shiny Hero motorcycles designed and built in India.

Steps away, men of similar age wait inside a sweltering recruitment agency with their passports and medical papers. Many have traveled on overnight trains from far corners of India with one hope: to leave the country and become laborers in the Middle East.

The dual realities reflect both the excitement and the uncertainty wrapped up in India’s impressive economic growth statistics, which Prime Minister Narendra Modi carries with him to Washington this week on his latest mission to strengthen ties with the United States.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

The Indian government reported last week that its gross domestic product – the total value of goods and services it produces – rose by 7.6% from the previous year, cementing its status as the world’s fastest growing major economy.

Amid a slowdown in China and crises in Brazil, Russia and South Africa, India is a bright spot for global investors and an increasingly important market for U.S. technology, defense equipment and capital investment. In a three-day visit including a luncheon with President Obama and a speech to Congress, Modi is expected to tout the expansion on his watch and make the pitch for more U.S. involvement.

But if the growth in Asia’s third-largest economy has put motorcycles, modern apartments and other middle-class dreams within reach for millions, it is also leaving large numbers of Indians behind. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Mumbai, India’s most mashed-up megacity, where lavish penthouses with private pools overlook seas of tin-roofed shanties where half the 12 million residents live.

In the bayside neighborhood of Mahim, the Hero motorcycle dealership abuts a construction site where strands of steel rebar stick out of half-built concrete pillars like fistfuls of uncooked spaghetti. Developers are planning a 24-story, ocean-themed luxury tower dubbed Miami, one of dozens of deluxe high-rises that have erupted around what was once a cluster of fishing villages.

At street level, the view is more modest but the changes equally striking.

Vikesh Shukla, 25, surveyed the motorcycle showroom where he has worked for six years since coming from a village in northern India. From a trainee job that paid less than $100 a month, Shukla is now in charge of the showroom and earns nearly $400 a month after bonuses.

The son of a farmer, Shukla said there were few jobs in his native Uttar Pradesh state. Hundreds of his college classmates applied in vain for government jobs or slid into struggling family businesses.

Shukla didn’t know anything about motorbikes when he started, but they have become one of the most prominent symbols of Indians’ expanding wallets. More than 16 million motorcycles were sold in the most recent fiscal year, a 40% increase from five years earlier, according to the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers.

“I like this job because I get to interact with different kinds of customers, from all different social classes and age groups,” said Shukla, who has the earnest eyes and neatly parted hair of an eager salesman. On a recent weekday, he helped a middle-aged oil rig worker and his wife purchase a red scooter priced at about $750.

“You see all of India here,” Shukla said.

Shukla struggled at first because he didn’t speak Marathi, the lingua franca of blue-collar Mumbai, but his loneliness eased after his younger brother followed him to the city. They shared a one-room suburban apartment, and Shukla used part of his earnings to enroll him in an engineering college.

This summer, his brother will start a training program at the Indian tech giant Infosys. Their father back in Bhadohi, a district about 400 miles southeast of New Delhi, could not be happier, he said.

“We’ve both come a long way from our village,” Shukla said.

The brothers are emblems of the improvements in domestic manufacturing and technology services that Modi has pushed for since taking office two years ago.

Yet economists worry that India’s economy still faces deep structural problems and isn’t creating enough jobs for the 7.5 million Indians who come of working age every year.

“Obviously it is very good news that the numbers are showing a clear uptick,” said Santosh Mehrotra, an economist at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. “But there are still major weaknesses.”

According to official statistics, India created only 135,000 new jobs in eight labor-intensive industries in 2015, the lowest figure since records started being kept in 2009. Some of the fastest growing sectors are finance, real estate and retail sales – not traditionally big employers.

“Automobile sales are growing, cellphone sales are growing…but these will not create jobs for the vast masses, especially with education levels increasing,” Mehrotra said.

Half of India’s workforce is still in agriculture, leaving millions of families vulnerable to drought and other climate shocks. While access to highways and electricity has improved across much of rural India, many people continue to toil in India’s vast informal labor market, excluded from the glossy portrait of the new economy.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

“If there is growth, why are there no jobs for us?” said S.K. Chinu, 31, a laborer from north of Kolkata, 1,000 miles away. He was standing outside a recruitment agency on the other side of the street in Mahim, where flies buzzed around a fallen mango pit and a man slept on the pavement.

Chinu, who has shaggy hair and betel-stained teeth, had a high school education but could only find odd jobs in his native town. His father had given up a fruit-selling business and there were no factory jobs nearby, Chinu said.

He had already done one stint as a migrant laborer in Saudi Arabia on a cleaning crew at the airport in Jeddah. His employer confiscated his passport – a common practice – but he made nearly $300 a month, three times what he figured he could earn back home.

Now he was headed back to Saudi Arabia, leaving behind his wife and two young children. He clutched a sheaf of medical records to submit to the agency, which told him to be ready to leave within a week for a job he didn’t yet know.

“No one likes to leave his country,” Chinu said. “But there is money abroad, so it’s worth it.”

Follow @SBengali on Twitter for more news from South Asia

MORE WORLD NEWS

Lancome draws outrage in Hong Kong after dropping pro-democracy pop singer

Islamic State’s Syrian capital becomes the prize in an international fight for legitimacy

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.