Shuttered Tokyo hotel reopens for evacuees

- Share via

Reporting from Tokyo — Room 1648 at the upscale Grand Prince Hotel Akasaka isn’t fancy, but it sure beats Mina Ariga’s old digs: an evacuation shelter in the Tokyo convention center. And for the three months she’ll stay, she won’t have to pay a cent.

She and her husband, Naruto, have been on the move since the earthquake and tsunami tore through the two-story home they were renting in Iwaki, a city about 20 miles south of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. For the last month, the couple and their three pugs have crashed with friends and slept in shelters.

On Saturday morning, Ariga “checked in” and threw herself onto the L-shaped couch in the corner of the room. She gave it a couple of pats. “Ah, it’s so relaxing here,” she said.

Never mind that the beige carpet is a little worse for the wear, she had a view of the leafy grounds of the Imperial Palace.

The hotel isn’t open for business. It saw off its last customers at the end of March, more than five decades after the original wooden-framed wing was built. The owner, the Prince Hotels group, has plans to tear down the aluminum-sided 40-story tower, which was designed by Japanese architect Kenzo Tange and opened in 1983.

But that won’t happen until the end of June. In the meantime, the hotel has worked out an arrangement with the Tokyo city government to open some of the 715 rooms to quake evacuees.

It’s one of the more creative ways that government officials have managed to absorb the exodus from Japan’s disaster-stricken northern regions. Other towns and cities have opened sports arenas, convention centers and abandoned schools to take in evacuees. Even Emperor Akihito offered his hospitality: He ordered the Imperial Household Agency to open the staff bathhouse at his summer home in Nasu.

Tokyo city officials say the Grand Prince will house 360 of the 850 people who have been living in shelters around the capital for weeks. The metropolitan government will pick up the $2.4-million tab for the utilities, guests’ meals and a bare-bones staff of 55.

The Grand Prince’s royal-sounding name used to be fitting. The land was previously owned by a man whose father was a shogun, or warrior leader, during Japan’s medieval period. The hotel lobby boasts white Carrara marble from Italy. Its location near Kasumigaseki, the central government’s seat , made it a favorite among bigwig politicians.

With the hotel’s closure, the grandeur has given way to more practical considerations. The front desk is dark and the sofas designed by Tange are gone from the lobby. Inside the elevator, makeshift labels pasted over the engraved plaques read “convenience store” and “cafeteria.” A 15th-floor meeting room is now a playroom. Downstairs from the lobby and past a white piano, the banquet area has about 20 washer-dryer units.

Tokyo city officials are betting that the evacuees will be ready to go home by the time the wrecking crews arrive.

“Hopefully, the nuclear plant will be under control by then,” Tokyo city official Tetsuya Wakimoto said Saturday. And if it isn’t? “We can’t just tell them to leave. We will need to find another place.”

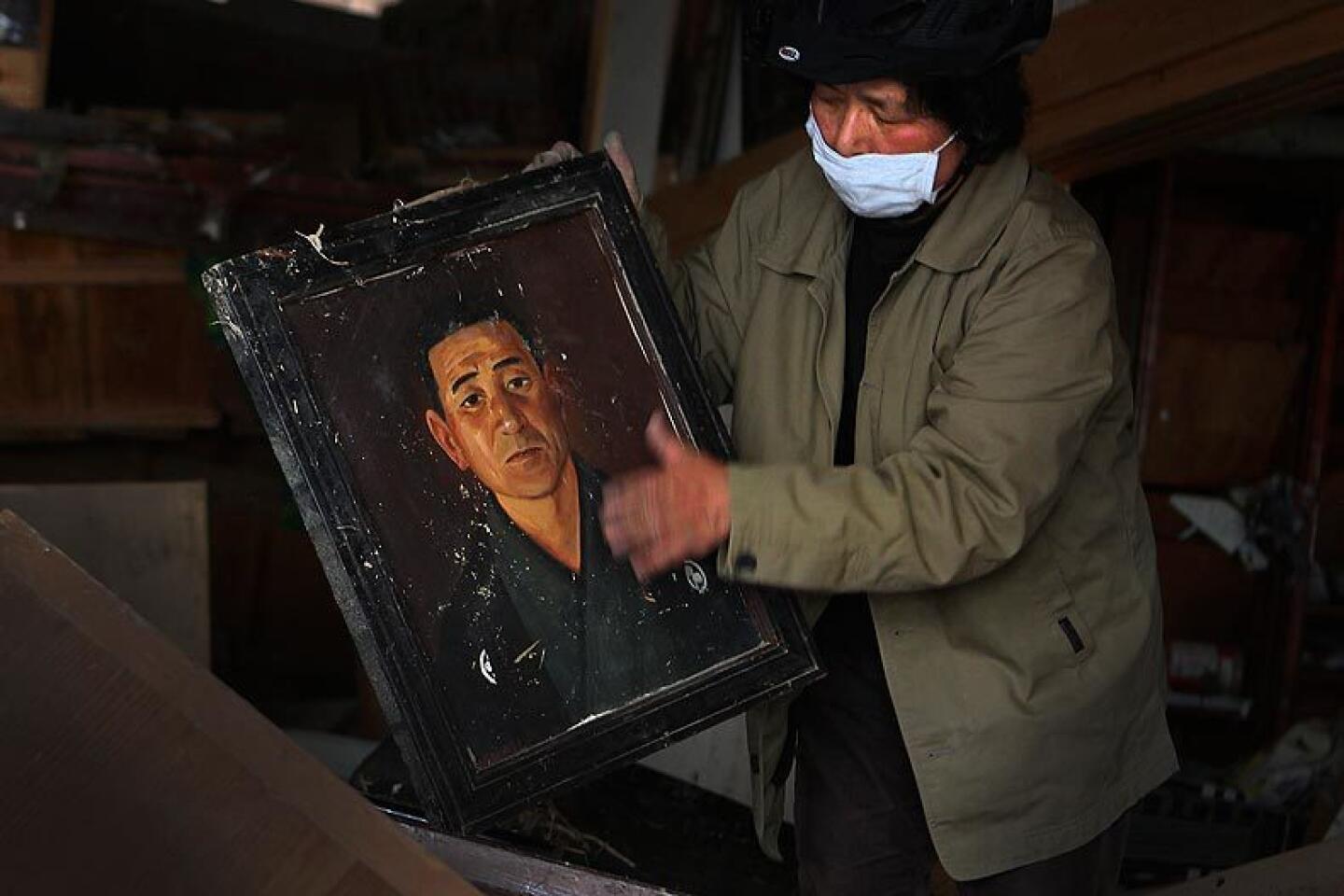

Hiroko Matsumoto, who checked into the hotel in the afternoon, isn’t sure she’ll be going back to Iwaki soon. After the explosions at the Fukushima plant, Iwaki officials had recommended wearing masks and hats and staying indoors. The 31-year-old homemaker said the market shelves were bare and hospitals where she buys medicine for her parents were closed. Her car had a little fuel, but gas stations were closed or suffered from shortages. The city emptied.

Matsumoto called her husband, who was working in Tokyo, and asked him to come get her, their 5-year-old son and her parents.

“The government was sending mixed messages, saying it’s safe for Iwaki residents to stay but that vegetables grown on land farther away from the nuclear plant are contaminated,” Matsumoto said. “I don’t trust the government.”

Others say three months is too short a time to rebuild a life.

Ariga said she and her husband would look for jobs before housing. She’s grateful for the hotel room, but her mind isn’t easy.

“The room is comfortable,” she said, “but I’m still very worried about the future.”

Hall is a special correspondent.

Times staff writer Julie Makinen contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.