Families want answers from man who says he dissolved 300 people

- Share via

Reporting from Tijuana — Fernando Ocegueda hasn’t seen his son since gunmen dragged the college student from the family’s house three years ago. Alma Diaz wonders what happened to her son, Eric, a Mexicali police officer who left a party in 1995 and never returned.

Arturo Davila still pounds on police doors looking for answers 11 years after his daughter and a girlfriend were kidnapped in downtown Ensenada.

For the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of families of people who have vanished amid Baja California’s drug wars, the search for justice has been lonely and fruitless. But their hopes have been buoyed recently by the Jan. 22 arrest of a man Mexican authorities believe is behind the gruesome disposal of bodies in vats of industrial chemicals.

Santiago Meza Lopez, a stocky 45-year-old taken into custody after a raid near Ensenada, was identified as the pozolero who liquefied the bodies of victims for lieutenants of the Arellano Felix drug cartel. Authorities say he laid claim to stuffing 300 bodies into barrels of lye, then dumping some of the liquefied remains in a pit in a hillside compound in eastern Tijuana.

His capture riveted Mexico with sickening details behind drug violence that has left more than 8,000 dead in two years. For the families of the disappeared, however, it was a chance to revive cases that seemed long forgotten.

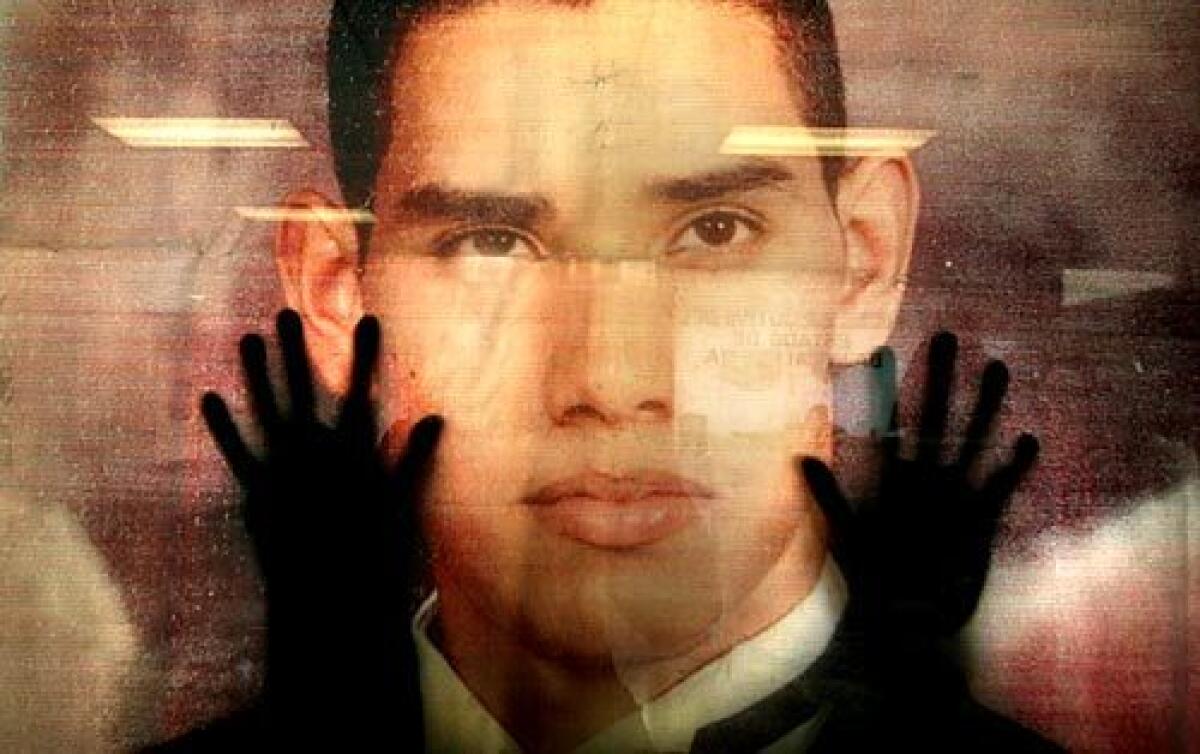

A day after Meza’s arrest, Ocegueda and 40 other people showed up at the federal attorney general’s office in Tijuana, with family snapshots in hand, demanding that authorities query Meza about whether he recalled dissolving their missing loved ones.

In the following days, dozens more people came forward with tales of disappearances. “Please help me find out what happened to him,” wrote one woman on a photograph of a young man smiling in a car. “He was my husband.”

Victim rights groups estimate that there are more than 1,000 people missing in Baja California, including students, businessmen, merchants and cops. Their cases have been ignored, bungled or blocked by law enforcement officials, activists say.

As a potential cartel insider, Meza could peel back the mysteries surrounding the disappearances, they say. Ocegueda, president of the Citizens United Against Impunity, plans to visit Mexico City this week, where he will request a personal audience with Meza.

Authorities are unlikely to grant access to the suspect, but families hope they’ll follow through on their promise to confront him with the photos. His capture has provided their greatest leverage against a government that for years has paid little attention to their concerns, said Ocegueda and other group leaders.

“The government wants to silence what cannot be silenced . . . but they didn’t count on someone saying that he personally disintegrated 300 bodies,” said Cristina Palacios Hodoyan, whose son, Alejandro, disappeared in 1997. “They’re going to have to pay attention to us now.”

Federal authorities have told the local media that they are cooperating with the families, having met with them and taken more than 100 photos.

The hillside compound where Meza told authorities he labored lies in an area acquainted with death. There are two cemeteries tucked in the surrounding hills, and funeral processions pass by daily on potholed Ojo de Agua road.

Behind the white gate, Meza said, he would fill a barrel with water and two large bags of lye. Wearing gloves and protective goggles, he’d light a fire underneath, and bring the liquid to a boil before depositing a body. After 24 hours, he would dump the disintegrated remains in a pit and set them aflame.

In Tijuana, the process is known as making pozole. That’s because the pink liquid in the barrel resembles the popular Mexican stew. When a Mexican official asked Meza what he did for a living, he replied, “Me llaman el Pozolero”: They call me the Pozole Maker.

He earned $600 weekly and said he learned how to disintegrate bodies by first experimenting with pig legs, according to the Mexican federal attorney general’s office. Meza allegedly told authorities he worked for several top cartel lieutenants over a 10-year period, most recently for Teodoro Garcia Simental, whom authorities believe is behind the kidnappings of hundreds of people in recent years.

Meza’s alleged deeds apparently went unnoticed in the shabby area of ranches and pig and chicken farms. Several neighbors said they had never seen him, and weren’t curious. “It’s best to be ignorant of such diabolical things,” said a local pig farmer, who did not want to be identified because he feared for his safety.

Ocegueda, a slender, intense man with a chain-smoking habit, vows to shatter that ignorance. After his 23-year-old son, Fernando, was kidnapped, authorities did little, so Ocegueda investigated on his own. He donned dirty clothes and a hooded shirt and rode a wobbly bike in tough neighborhoods, chatting up drug dealers and other criminals.

These days he leads demonstrations, camps out at City Hall, and corners military and government officials any chance he gets. After Meza’s arrest he went to the San Diego area to meet with 20 families who gave him photographs of loved ones, some of them U.S. citizens, who vanished while going to work or visiting relatives in Mexico.

Ocegueda believes he knows the identities of his son’s kidnappers. But his probe, like others, hit a dead end. He believes police protect organized crime members, fear investigations will reveal their own complicity, or are incompetent. Some families have been threatened by police after reporting the crimes. In one case, a man who reported the abduction of his family was kidnapped himself the next day, said Ocegueda, whose claims are supported by many families and a Mexicali-based group, the Hope Assn. Against Kidnapping and Impunity.

“Authorities have told people not to report anything, saying their loved ones were criminals. . . . Instead of helping resolve their cases, they threaten them,” said Miguel Garcia, a Mexicali-based attorney who provides legal advice to the Hope Assn.

Last year, the groups gained a key ally when the then-top military commander in the region, Gen. Sergio Aponte Polito, accused several state law enforcement officials of links to organized crime. Among them, he said, was the head of the state anti-kidnapping squad in Tijuana.

Aponte was removed from his post in August, and most of the state officials he accused have not been prosecuted.

Last week at Meza’s compound, federal agents continued digging up soil samples looking for human remains. Experts and law enforcement say chances are slim they will be able to identify any of them.

Salvador Ortiz Morales, the state deputy attorney general in Tijuana, said forensic teams have never been able to identify victims dissolved in barrels because so little remains.

The site may not yield answers for another reason.

Meza admitted disintegrating bodies over a 10-year period, but neighbors said the compound was constructed only six months ago. All the more reason, the families say, to pressure Meza to disclose other grave sites, and demand other details on the fate of the missing.

“There are many other families suffering like me,” Ocegueda said. “We need to find out what he knows.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.