‘My God. We’ve done this’: Meet the reporters who probed the Panama Papers

- Share via

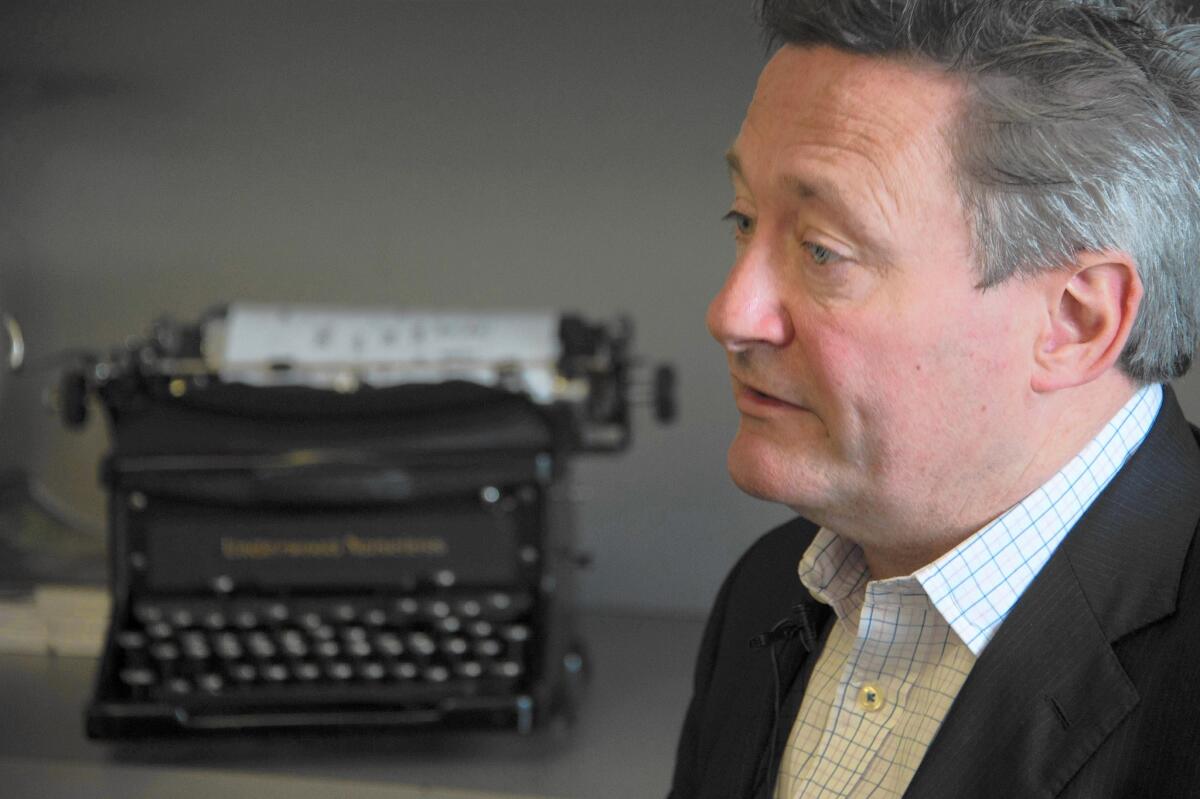

When Gerard Ryle saw a photograph of thousands of protesters gathered outside Iceland’s Parliament this week, a thought flickered through his mind: “My God. We’ve done this.”

It was true. Iceland’s prime minister stepped down from office Tuesday — the most significant fallout so far of the work by journalists collaborating with Ryle’s International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Over the weekend, hundreds of reporters in more than 70 countries unveiled a nearly yearlong global investigation and began publishing a series of articles on millions of leaked financial documents they dubbed the “Panama Papers,” a trove of information bigger than anything WikiLeaks or Edward Snowden ever obtained.

FULL COVERAGE: Panama Papers document leak>>

The effect has been like shining a flashlight into a series of dark rooms packed with money and lies. The documents leaked from the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca — and examined by journalists at outlets including the Guardian, the BBC and the Miami Herald — have forced global leaders and public figures to answer for the massive amounts of wealth they had hidden in offshore tax havens, outside the scrutiny of auditors and voters.

But the story started small, with an anonymous writer’s message to the German newspaper Sueddeutsche Zeitung in early 2015: “Hello. This is John Doe. Interested in data?”

The newspaper was interested, of course. But the source said there were conditions: “My life is in danger. We will only chat over encrypted files. No meeting, ever.”

“Why are you doing this?” a journalist at the newspaper asked the source, according to an account published this weekend.

“I want to make these crimes public.”

The documents sent to the newspaper stretched back decades and were unwieldy. They included bank records, emails, phone numbers and photocopies of passports held by Mossack Fonseca to track its clients. But there was no road map to show what they all meant.

It was like trying to read an MRI without a doctor.

Seeking help, the Sueddeutsche Zeitung reached out to Ryle’s consortium, a global network of journalists that had handled document leaks from the HSBC bank and the tiny European nation of Luxembourg.

The network is overseen by the Washington-based Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit known for its muckraking journalism in the United States. The two share offices on different floors of the same building.

They are not large-scale journalistic operations. The Center for Public Integrity’s typical yearly revenue is less than $10 million — mostly grants from other nonprofits such as the Omidyar Network Fund and the Knight Foundation. Ryle said the international consortium has only about four staff members in Washington, with others scattered around the world, mostly working from their homes.

But Ryle was game to help out the Germans with the sprawling Panama leak. He flew to Munich and spent four days reviewing the material. “It was pretty obvious at that point we had something big,” Ryle said in an interview Tuesday.

He secured partnerships from the BBC, the Guardian and the McClatchy newspaper chain in the U.S. During one early meeting in Munich of at least 100 journalists from around the world, Ryle felt nervous as he pitched them on a close collaboration that would require teamwork and strict secrecy.

“If they only knew how scared I was,” Ryle said this week.

But they bought in. The consortium’s data journalists began indexing the documents and building a searchable database. The group also built an internal social network so that members could chat with one another from around the globe. British reporters who found French documents could ask French reporters what they meant.

Holly Watt, an investigative reporter for the Guardian in London, said the cache of documents was so massive that a search could leave the computer “just smoldering in a corner” for three days as the journalists awaited the results.

“We would have moments of being like, ‘Oh my gosh, so and so has an account here,’” said Watt. The investigation stretched on for so many months that her friends and family wondered why her byline had disappeared from the newspaper.

“Sometimes you would look at so much data your eyes would completely glaze over,” she said.

Many searches simply involved typing in names of prominent politicians or donors to see if anything turned up, said Kevin Hall, the Washington-based chief economics correspondent for McClatchy. But the sense of camaraderie among the journalists grew as they shared tips and findings.

“You all felt like you were on this big expedition together,” Hall said.

Journalists from the news outlet Fusion traveled to Delaware to examine how incorporation worked in the U.S. and stared at one-story buildings that were allegedly the home of thousands of corporations. Last month they traveled to Panama, where at least seven allied news crews from international outlets assembled in Mossack Fonseca’s building to pressure someone from the firm to come out and speak with them.

“We showed up, we stood downstairs,” said Alice Brennan, an investigative producer with Fusion. “I felt like I was a college student picketing.”

Nicholas Nehamas, a Miami Herald real estate reporter, said he knew that foreign wealth had helped snatch up Miami property. But in an era of diminished resources and staff at U.S. newspapers, he could not figure out the identities of the Brazilians, Italians and Argentines doing the buying — until he started collaborating with Brazilian, Italian and Argentine reporters on the “Panama Papers.”

“A lot of it was an ‘aha!’ moment where I’m digging through the files, and I’m seeing a convoluted offshore transaction,” Nehamas said. He’d post it to the consortium’s secured chat group, and “within an hour I’d have three responses being like, ‘Oh my God, this guy was arrested for corruption.’”

Ryle said the consortium didn’t have any members in Iceland but ultimately signed up an independent journalist, Johannes Kr. Kristjansson, to investigate Iceland’s prime minister.

Documents showed the prime minister, Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, and his wife, through an offshore corporation called Wintris, had held an undisclosed financial stake in the Icelandic banks that collapsed in 2008. It was a potentially serious conflict of interest for a politician in a country still enraged by the financial meltdown, and it would be up to Kristjansson to do the reporting.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

“The pressure on him — he was the loneliest man in the world for months,” Ryle said of Kristjansson.

His work came to a head in March. The prime minister, Gunnlaugsson, walked out of an interview on video when confronted about his undisclosed stake in Wintris. Gunnlaugsson’s wife soon claimed that her husband’s stake had been an error made by the bank.

After the investigation and the interview aired Sunday — and protesters began to gather Monday — Kristjansson sent a message to Ryle: “Wintris has arrived.”

The next day, amid mounting pressure, Gunnlaugsson stepped down from office.

MORE WORLD NEWS

Bangladeshi surfer girls go against the cultural tide

Stung by Trump’s attacks, Mexico names ambassador to U.S. who is expected to fight back

Syrian rebels have long wanted anti-aircraft missiles. Their wish may have been granted

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.