India limits social media after civil unrest

- Share via

NEW DELHI — Has the Indian government lost its sense of humor?

That’s what some in India were asking as word spread that authorities had pressured Twitter into blocking several accounts parodying the prime minister after civil unrest that saw dozens of people from northeastern India killed and thousands flee in panic.

This week, the government also imposed a two-week limit of five text messages a day — raised Thursday to 20 — potentially affecting hundreds of millions of people, and pressured local Internet companies as well as Facebook, Twitter and Google to block hundreds of websites and user accounts.

Although journalists, free speech advocates and bloggers said the effort to squelch rumors may be justified, several criticized the actions as excessive.

“You cannot burn the entire house to kill one mischievous mouse,” said Gyana Ranjan Swain, a senior editor at Voice & Data, a networking trade magazine. “You’re in the 21st century. Their thinking is still 50 years old. It’s just ‘kill the messenger.’”

Comedians said Indian political humor is evolving and there’s more leeway to make fun of politicians than a decade ago, but the nation’s mores still call for greater respect than in the West.

“If I tried something like South Park, I’d be put behind bars tomorrow,” said Rahul Roushan, founder of Faking News website, which satirizes Indian current events.

Faking News has lampooned the recent corruption scandals, including specious stories about theme restaurants (where customers must bribe waiters or go hungry); and a tongue-in-cheek report that India has banned the zero because too many of them appear nowadays in auditors’ reports, after recent coal and telecommunications scandals each allegedly involving more than $30 billion.

Roushan, whose site isn’t blocked, said he hopes low-level officials misinterpreted government directives.

“I’m still in a state of disbelief,” he said. “I don’t think the government is so stupid that it can ask that parody accounts get taken down. If they did, God help this country.”

A spokesman for the prime minister’s office said the blocking of six fake Twitter accounts attributed to the prime minister has been in the works for months and wasn’t related to the recent crisis. He said the move was in response to tweets containing hate language and caste insults that readers could easily mistake as the Indian leader’s. A dozen Twitter accounts and about 300 websites were blocked, according to news reports.

“We have not lost our sense of humor,” said Pankaj Pachauri, the prime minister’s spokesman. “We started a procedure to take action against people misrepresenting themselves.”

But some Twitter users whose accounts are frozen, including media consultant Kanchan Gupta, counter that the government may be using the crisis to muzzle critics.

“I’m very clear in my mind this is a political decision,” said Gupta, who has been critical of corruption and the government’s policy drift. “If they were openly confrontational of me, they’d go nowhere, so they’re trying this.”

Attempts to access his Twitter page Thursday were met with the message: “This website/URL has been blocked until further notice either pursuant to Court orders or on the Directions issued by the Department of Telecommunications.”

Even Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II has numerous parody accounts so India needs to lighten up, consultant Gupta said.

He’s received several messages from worried Pakistani friends since the news broke. “They ask if I’m all right, say they hope they haven’t frog-marched you to jail,” he said. “What irony.”

The restrictions are the latest chapter of a crisis that started in July when Muslims and members of the Bodo tribal community in northeastern India clashed over land, jobs and politics. The result: 75 people killed and 300,000 displaced.

Muslims in Mumbai, formerly Bombay, staged a sympathy demonstration last week; two more people were killed and dozens injured.

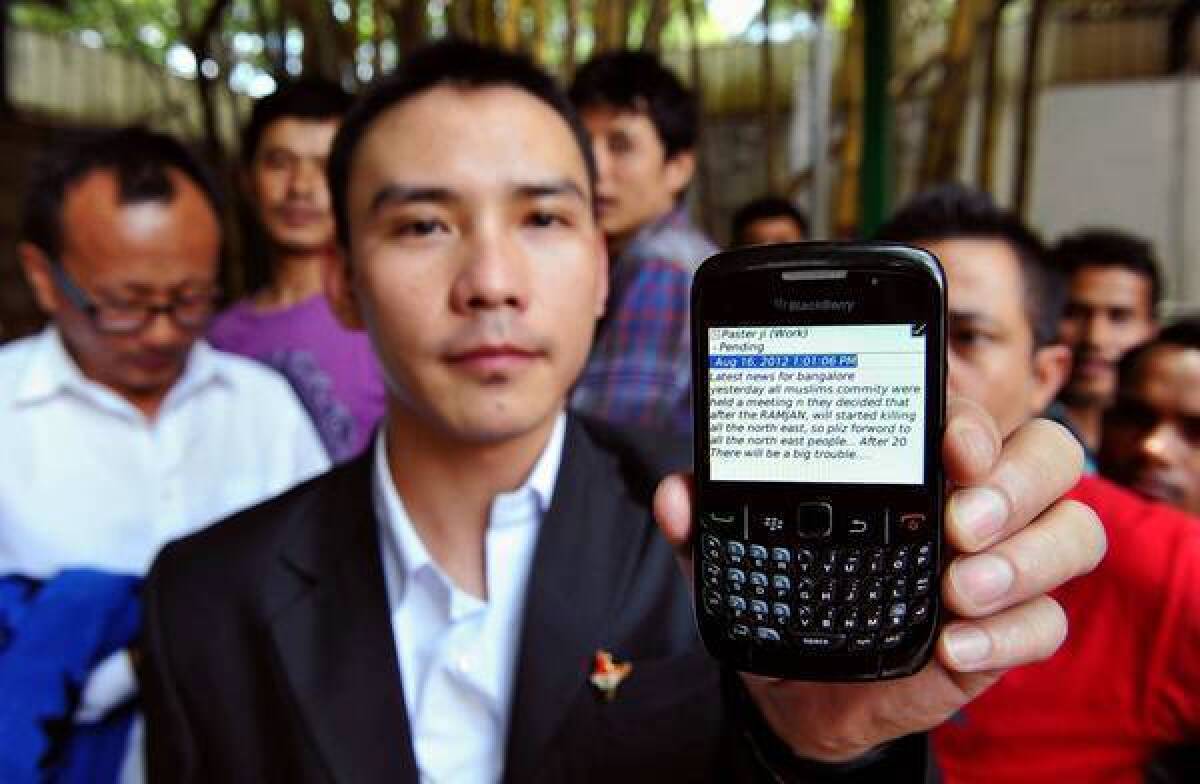

Rumors, hate messages and altered photos of supposed atrocities against Muslims soon spread on social media sites, and several people from northeastern India were beaten in Bangalore and other cities, prompting the crackdown.

New Delhi has accused Pakistani websites of fanning the online rumors. (Islamabad said it would investigate if there’s any proof.) But Indian news media also reported that 20% of the websites blocked contained inflammatory material uploaded by Hindu nationalist groups in India that were apparently trying to stir up sectarian trouble.

The Twitter community has responded with derision and humor to limits on text messages on prepaid cellphones.

“Feeling deeply insulted that I still have not been blocked,” tweeted user @abhijitmajumder. “Victim of govt apathy.”

Sunil Abraham, head of the Bangalore civic group Center for Internet and Society, said this week’s restrictions are the latest in a series of regulations and recommendations aimed at tightening Internet control.

“Before, the government’s had no grounds for censorship, it was only acting on the bruised egos of bureaucrats and officials,” he said. “This time, it’s got a legitimate right given the disruption of public order. But it hasn’t done so very effectively.”

Instead of imposing wholesale restrictions, including the blocking of a Pakistani site that was debunking the online rumors and doctored photos, the government should have tailored its censorship to target offensive pages, reacted much faster and used the same social networks to counter misinformation, several analysts said.

Vague Indian censorship laws also afford room for abuse, some said, allowing the targeting of critics who don’t pose a national security threat.

U.S. State Department spokeswoman Victoria Nuland on Wednesday urged India to respect Internet freedom. Facebook said in a statement it was “working through” requests from the Indian government to filter content. The Google Transparency report has India as one of the countries topping the list of those that routinely asked Internet companies to remove content in 2011.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.