Ireland votes on EU referendum to rein in Eurozone debt

- Share via

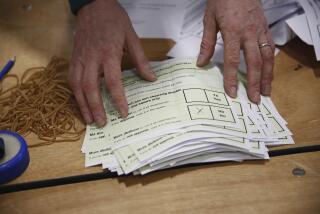

LONDON — Irish voters went to the polls Thursday to decide whether to ratify a treaty aimed at controlling the runaway deficits of European Union countries.

The referendum, whose results are expected Friday night, comes as worry about Spain’s economy continued to roil markets worldwide. Spanish stocks recovered some of their losses Thursday after slumping to nine-year lows a day earlier. The euro lost ground against the dollar, and oil prices fell, all on fear that Madrid will need international help to rescue its ailing banks.

The German-backed fiscal treaty calls on countries to limit spending and stick to budgetary targets. It aims to coordinate EU fiscal and budget policies and hold annual structural deficits within 0.5% of gross domestic product, with bailout funds from the so-called European Stability Mechanism available to those that ratify the treaty.

Fines are to be imposed on those that fail to comply with debt targets.

Ireland is the only country to put the EU plan to a public vote. Irish constitutional law requires public approval for major reforms.

Of the 27 EU nations, Britain and the Czech Republic have opted out of the treaty, which must be ratified by 12 of the 17 states in the Eurozone — the bloc that shares the euro currency — by March. So far, Romania, Slovenia, Portugal and Greece have approved it.

Polls indicate that the treaty, which would result in more austerity and continued access to rescue funds, will pass. But Ireland has had a quixotic record on EU treaties.

Two previous referendums — on EU expansion in 2001 and on a more streamlined EU administration in 2008 — were rejected by Irish voters, then accepted in a second vote after amendments. This time there will be no second vote for Ireland.

The nation’s economy was saved in 2010 by a massive European bailout of $108 billion.

In a last appeal before the balloting, Prime Minister Enda Kenny urged Ireland’s 3.1 million voters to “vote yes on Thursday, yes to stability, yes to investment,” and give greater credibility to Ireland when it takes over the EU presidency in January.

Fierce criticism of the measure has come from the Sinn Fein opposition party, once the political arm of the outlawed Irish Republican Army revolutionaries in the British province of Northern Ireland but now a legitimate and popular left-wing force in the province and in Ireland. Party leader Gerry Adams told voters not to give up their say over Irish economic policy and “not to write austerity into the constitution.”

In Spain, meanwhile, economic uncertainty continued to fester. A spokesman for the European Commission, the EU’s executive body, told Spanish national radio that Spain needed to speak up immediately if it needed outside aid.

Madrid is reportedly more than $12 billion short on funds to bail out Bankia, the country’s largest real estate lender. The government has said it will devote $24 billion in taxpayer money to prop up the bank. Unconventional plans to use treasury bonds or other assets to rescue it have been nixed by the European Central Bank.

The interest rate on Spain’s benchmark 10-year bonds brushed 6.7% on secondary markets, just shy of the 7% mark that sent Greece, Ireland and Portugal into bailouts.

Those rising bond yields, along with a previously unannounced trip by a top Spanish official to Washington, fueled fear that a bailout might be imminent. Deputy Prime Minister Soraya Saenz de Santamaria flew to Washington late Wednesday to meet with Treasury Secretary Timothy F. Geithner and International Monetary Fund chief Christine Lagarde, a visit the Spanish government announced only after she had left.

An IMF spokesman in Washington said Saenz de Santamaria’s meeting with Lagarde, scheduled for Thursday afternoon, did not signify talks with Spain over possible financial assistance.

Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank, spoke Thursday to the European Parliament in Brussels, where he said the euro currency framework that was set up in 1999 was no longer sustainable to manage the debts that too many Eurozone governments had allowed to escalate.

The ECB is no longer able to “fill the vacuum of the lack of action by national governments,” Draghi said, warning European leaders to take a longer view of debt-reduction strategies. Rising Eurozone debt needs greater central governance, particularly with recapitalization of failing banks, he said.

Governments tend to underestimate final bank losses, Draghi said. “There is a first assessment, then a second, a third, a fourth … the worst possible way of doing things. Everyone ends up doing the right thing, but at the highest cost.

“Bankia and other cases show that decisions on recapitalization are probably simpler to manage if the decision is more centralized,” he said, recommending that recapitalization be done not by national governments but by the European Stability Mechanism, the new EU rescue fund.

“The issue is not so much if ESM money could be used to recapitalize banks, but whether this could be done directly without having to go through governments,” he said.

Stobart is a news assistant in The Times’ London bureau.

Special correspondent Lauren Frayer in Madrid contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.