Violent soccer youths cast chill over Egypt

- Share via

CAIRO — It is a day of street clashes outside the U.S. Embassy, and “the boys” are out. The word buzzes throughout Tahrir Square: The Ultras are here.

A scrum of young men charges toward police, amped on adrenaline and gasoline bombs. Across the road, men and women on their way home bat their eyes at the acrid puffs of tear gas.

Tens of thousands strong, these fans of Cairo’s two top soccer teams became the shock troops of the revolution nearly two years ago, willing to barrel into slugfests with the forces supporting President Hosni Mubarak. Combining the aggression of the hoodlums in “A Clockwork Orange” and the anarchy of the Sex Pistols — “Don’t know what I want, but I know how to get it” — the Ultras have since cast a chill over Egyptian society.

Cagey about being co-opted, they scorn meetings with political parties that have ascended since Mubarak’s downfall, including the increasingly powerful Muslim Brotherhood, and take orders instead from “capos” in neighborhoods given special names. (Giza, home to the pyramids, is known in Ultra speak as the State of Booboo.)

The Ultras don’t seem to know what they’re fighting for, only what they’re fighting against.

When pushed, they can list what they like — freedom, soccer and finding a job — and what they don’t — the army, the police and basically anyone in power.

One Ultra who supports the White Knights of Zamaluk soccer team lingers on the edge of Tahrir Square after a tear gas shell thumps his leg. His Ultra name is Ili because he always wanted an Italian-sounding alias. Ili and his pack of White Knights dress alike: tight jeans and secondhand T-shirts, their hair faded on the sides and curly or moussed on top.

“Why not burn up a police truck?” they say, almost in unison. “If we don’t burn their trucks, they’ll hurt us.”

***

In a country where uncertainty is the only certainty, the Ultras provide male teenagers and twentysomethings identity through their chants, their code of honor and their team colors: white for the White Knights, red for the Al Ahly Red Devils. Their ranks have swollen since the revolution as more disenfranchised teenagers find their call irresistible. A leading Ultra estimates the total at 20,000; some have put it even higher.

“The boys,” hardened by the deaths of friends in the revolution, are long past being just devoted soccer fans, with one sportscaster criticizing them as “a state within a state.”

“Their emotions are running high, and now they feel they have a responsibility to bring justice to their dead friends and colleagues,” sociologist Ammar Ali Hassan said. “They will always rise against the system if the occasion calls.”

In their restlessness and their instinct for violence, the Ultras resemble young people across the Arab world who have risen up against decades-old regimes.

Formed in 2007 by sports enthusiasts ranging from unemployed college graduates to bored teenagers, the Ultras quickly fell into the cross-hairs of Mubarak’s security forces, who were made nervous by the emergence of large, organized groups of young men.

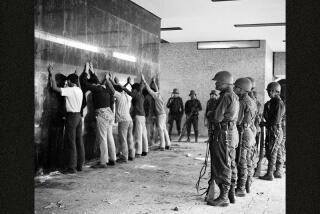

Before any games, Ultras were routinely arrested and their placards confiscated. During the matches, fights often broke out between police and Ultras, rather than between fans of the two teams, who have a Yankees-Red Sox-style rivalry.

So when large-scale protests against Mubarak’s iron-fisted rule began in Tahrir Square on Jan. 25, 2011, Ultra members eagerly joined in. Already accustomed to brawling, they charged buildings and helped hold the line when Mubarak supporters sought to storm the square on camels.

In the months after Mubarak’s exit, the Ultras’ stance became edgier. At a soccer match last fall, police arrested half a dozen Al Ahly Ultras. In return, the Ultras started holding sit-ins and flashing giant posters of their jailed friends at matches. At the end of 2011, when violent clashes erupted between protesters and police in Tahrir Square, all sides blamed the Ultras for fanning the flames.

The head-on style of confrontation, with blind devotion to the “revolution,” sped them toward a humbling disaster a year after Mubarak fell. At a February soccer game in the city of Port Said, members of the Al Ahly Ultras were attacked by local fans armed with knives. While police and army forces looked on, 74 of the Ultras were killed.

Sitting at a cafe recently, one of the Al Ahly Ultra founders, who declined to give his name, was smoking a cigarette after finishing his day job. What he saw that night in Port Said, he said, has scarred him.

Almost worst of all: the unbearable train ride home, silent except for the sound of Ultras calling their families to say: “I haven’t died.”

***

A week after the embassy skirmishes, Ili sits in Cilantro, a coffee shop on Mohammed Mahmoud Street. Day-Glo portraits of the revolution’s dead cover the walls outside.

Ili and a friend, an Ultra who goes by the name Meto, after an old Italian soccer player, are offended by the negative image. They don’t deny battling it out with police, but they see themselves as patriots. They are proud of the Ultras’ way of life.

They elaborate the movement’s principles, correcting one another like 1960s theoreticians enmeshed in the teachings of Mao. Whether an Ahly or Zamaluk fan, Ultras list their code as if it was the most noble calling on Earth:

1) Sacrifice for your team.

2) Always glorify the team, never the individual.

3) Always press for victory.

4) Stand with the team even in defeat.

5) Stand for freedom.

But for all their bravado, Ili and Meto sense that they have ever-shrinking opportunities. Ili has a law degree but works in a pharmacy. Meto is nearing an engineering degree and is staring at obligatory military service. “The day I stop cheering is the day I die,” Meto says, offering up one of the Al Ahly Ultras’ most popular cheers.

The Al Ahly Ultra cofounder understands why the young keep flocking to Al Ahly: The uniform, the songs and the cheers are intoxicating. He laughs at the allure. And it is this power he will use to make sure his friends’ deaths at Port Said are avenged.

“We do not want chaos, but chaos is possible,” he says. “We can get to anyone.”

Special correspondents Reem Abdellatif and Hassan El Naggar contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.