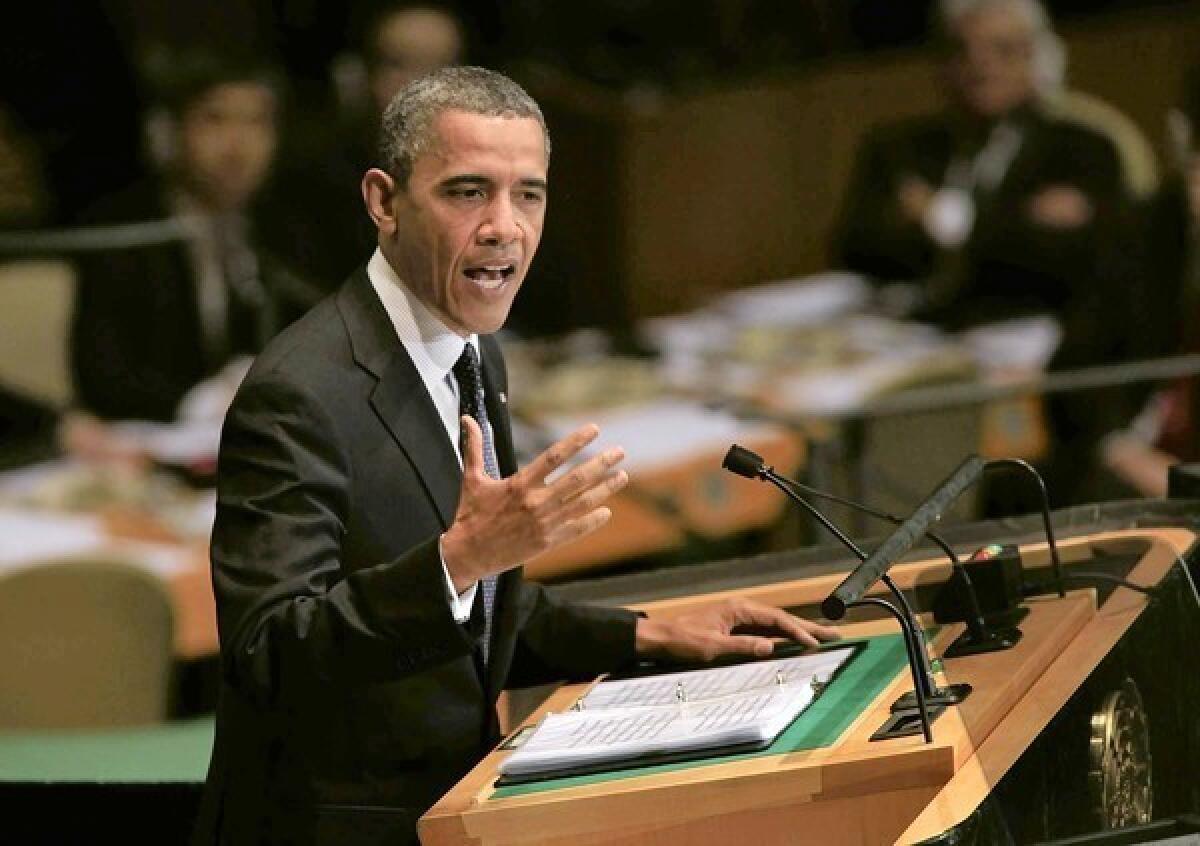

At U.N., Obama urges Muslim world to support free speech

- Share via

UNITED NATIONS — Warning of a deepening rift between the West and the Muslim world after two weeks of anti-American violence, President Obama used his annual U.N. address to urge Arab states to continue difficult political reforms without tolerating violence or curtailing free speech.

As he defended his own record in the turbulent aftermath of the “Arab Spring” revolutions, Obama vowed Tuesday that the United States would “do what we must to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon.” He called for a diplomatic solution to that crisis but added, “Time is not unlimited.”

Obama promised to press efforts to help end the conflict in Syria and replace its authoritarian government, and to push for a lasting Israeli-Palestinian peace deal. He did not say how he plans to make progress on either front.

Instead, he used his 30-minute speech to the U.N. General Assembly in the heat of a U.S. presidential campaign to offer an impassioned embrace of freedom of expression and a poignant appeal to end the anti-American riots that have erupted around the globe, killing dozens of people, including the U.S. ambassador to Libya and three other Americans.

Obama condemned the American-made anti-Islamic video that ostensibly sparked the protests, calling the video “crude and disgusting.” The film, he said, “is an insult not only to Muslims, but to America as well” because it embodies intolerance.

In the U.S., he said, “countless publications provoke offense. Like me, the majority of Americans are Christian, and yet we do not ban blasphemy against our most sacred beliefs.” As president, “I accept that people are going to call me awful things every day. And I will always defend their right to do so.”

The strongest weapon against hateful speech “is not repression; it is more speech” to rally people against bigotry, he said.

“Now I know that not all countries in this body share this particular understanding of the protection of free speech,” he said. But when anyone with a cellphone “can spread offensive views around the world with the click of a button, the notion that we can control the flow of information is obsolete.”

Since the video first sparked protests in Cairo, Muslim-led governments have demanded that Western leaders pass laws or take action to halt what they consider hate speech against Islam. Tension has increased as a result, rather than the harmony the White House had hoped would flourish after it supported popular uprisings last year in Egypt, Yemen, Libya and elsewhere.

No speech “justifies mindless violence,” Obama said. “There are no words that excuse the killing of innocents. There is no video that justifies an attack on an embassy.”

The president began his speech with an emotional tribute to the slain U.S. ambassador, J. Christopher Stevens, who he said had traveled to Benghazi to review plans to establish a new cultural center and to modernize a hospital. Stevens “embodied the best of America,” he said.

The turmoil in the Middle East, the deepening crisis in Syria and the standoff over Iran’s nuclear program have given Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney grist for criticizing Obama, and the president did not repeat his weekend comment that recent events were “bumps in the road” to democracy.

He dealt briefly with the conflict in Syria, where critics have charged that he needs to give greater support to rebels fighting President Bashar Assad. Obama said only that his administration “will stand with” Syrians who want a new order in their country.

He gave no hint of how he would move the stalled diplomatic effort aimed at persuading Iran to abandon its nuclear ambitions. He implied that his administration might turn to military action, but did not issue a specific “red line” that would trigger a confrontation, as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has publicly urged for weeks.

Obama had no meetings with other leaders, leaving those sessions to Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton. He did stop in briefly during a meeting between Yemeni President Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi and White House terrorism chief John Brennan.

Clinton met for about an hour with the U.N.’s new special envoy to Syria, Lakhdar Brahimi, who told her that he will need time to review the situation before he proposes a new approach to the conflict, a senior official said.

Brahimi said that after a round of talks in the region, he found Assad “intransigent” and the envoy was “not going to rush into putting a plan on the table,” the official said.

kathleen.hennessey@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.