Tight election in Venezuela complicates Nicolas Maduro’s plans

- Share via

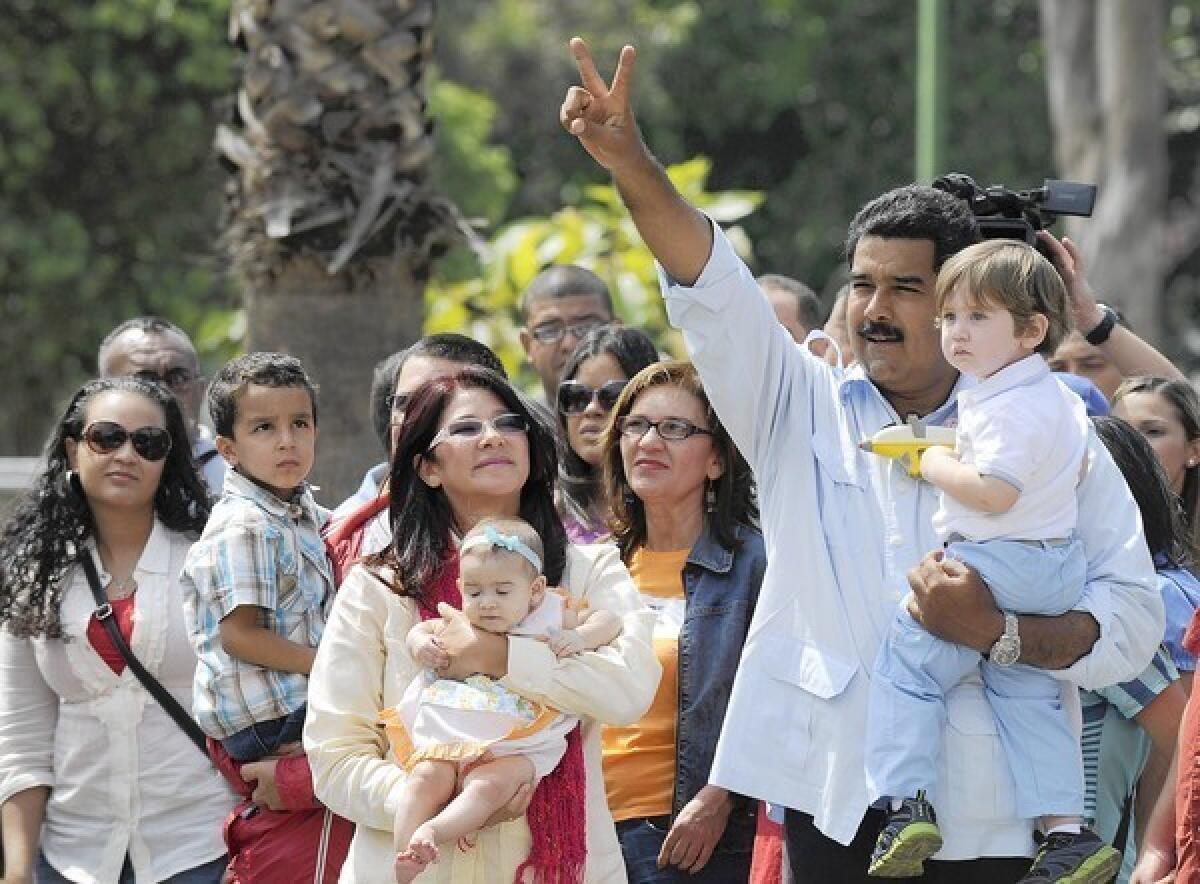

CARACAS, Venezuela — Nicolas Maduro’s narrow victory in an election to serve out the late Hugo Chavez’s presidential term in Venezuela will complicate tackling major issues on his agenda: fixing a crumbling economy, addressing violent crime and restoring relations with the United States.

The election results, coming amid allegations by rival Henrique Capriles of widespread voting abuses, will make governing this polarized country even more difficult because Maduro will lack the broader public support enjoyed by his colorful predecessor, analysts said Monday.

Maduro won Sunday by 1.5 percentage points; Chavez never triumphed in his four presidential elections by less than 10 percentage points, margins that strengthened the socialist’s claim of a popular mandate for his “Bolivarian revolution.”

Maduro, at one point leading Capriles in preelection polls by double digits, can make no such claims.

“The revolution almost slipped through Maduro’s fingers,” said political scientist Luis Salamanca, who described Sunday’s result as “an electoral victory but political rout.... He can’t govern with confrontations and insults as his mentor did. He won’t be able to manage the country that way.”

In addition to undercutting Maduro’s hope of wielding unchallenged authority, the close race could weaken his support inside the Chavismo movement, Salamanca said. Chavez managed, with charisma and no small amount of effort, to hold together his following’s many interest groups. For the less popular Maduro, a step toward austerity could lose him support among the poor, and an olive branch offered to the United States could cause the far left to turn on him.

All this comes as decisive measures are needed to plug holes in an economy fast taking on water.

Last year, the government spent about 40% more than it received in revenue, in part on welfare programs and election-year giveaways. As a percentage of economic output, its tide of red ink is worse than that facing economically troubled Greece, Spain and Portugal, said Francisco Ibarra, an economist with the Econometrica consulting firm in Caracas, the capital.

“The Chavistas didn’t invent poor economic management in Venezuela; they have just made it two or three times worse,” said Ibarra, and a day of reckoning may be approaching.

Despite a windfall in oil sales, the government’s coffers are depleted by external and domestic giveaways, including $6 billion a year in discounted oil to Chavez’s longtime ally Cuba. Domestic subsidies of gasoline prices — a tankful can cost motorists as little as 25 cents — are popular, if not assumed as a right by Venezuelans. But they cost the government as much as $3 billion a year.

“Building roads in Nicaragua, hospitals in Uruguay and paying the salaries of mayors in Bolivia diverts money badly needed in Venezuela,” Ibarra said.

Oil production, the main source of the government’s largesse, is in a downward glide because of lack of investment. There have been two devaluations of the nation’s currency in 2013, and the inflation rate is expected to exceed 30% this year.

A serious move to combat Venezuela’s spiraling violent crime — the homicide rate has quadrupled since 1999 — may force Maduro to divert government spending away from welfare programs and toward providing more resources and manpower for law enforcement. But reducing social spending carries enormous risks for a socialist government whose generosity is its selling point.

The risk of fracturing his socialist base could also make it more difficult for Maduro to repair relations with the United States, a move he has said he wants to make.

Well-placed sources say Maduro wants to get out from under the U.S. designation of Venezuela as a haven for drug traffickers and as being too amenable to nations such as Iran that the Americans view as state sponsors of terrorism.

Maduro reacted favorably to U.S. overtures in November when he was telephoned by Assistant Secretary of State Roberta Jacobson. The first step along the path — an exchange of counter-narcotics information — was in the works before the ailing Chavez, who died March 5 after a years-long battle with cancer, abruptly canceled the process, sources said.

Even as Maduro faces these challenges, Capriles is demanding a manual recount of all 14.8 million votes cast, a request that the National Electoral Council rejected Monday. It was unclear whether a partial or electronic recount would be carried out and what difference, if any, it could make to the outcome.

Still to be counted were the 30,000 votes of Venezuelans living abroad who cast ballots in foreign consulates, but they were not expected to materially change the outcome.

At a news conference, Capriles called on supporters to march on state offices of the election council to protest the decision. He vowed to lead a march to the agency’s national office in Caracas on Wednesday. He also called on supporters to show their displeasure by participating Monday night in a cacerolazo, or clanging of pots and pans, and the noise could be heard in the capital at dusk.

Although Venezuela has a modern vote-counting system, Capriles said Sunday night that his team had documented 3,200 instances of irregularities — including intimidation by armed Chavista militants, extended voting hours and the closing of the borders with Colombia and Brazil days before the balloting — that may have cost him votes.

Gustavo Palomares, a spokesman for one team of election observers from European countries invited by the opposition, said Monday that there was an unspecified number of abuses, including intimidation of voters at some polling places. He said he supported a recount.

In Washington, U.S. officials also called for a recount and urged Venezuela not to certify any results until one was completed.

Patrick Ventrell, a State Department spokesman, called it “an important, prudent and necessary step to ensure that all Venezuelans have confidence in these results.”

Kraul is a special correspondent. Special correspondent Mery Mogollon in Caracas and Times staff writer Paul Richter in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.