Nelson Mandela helped popularize use of sanctions

- Share via

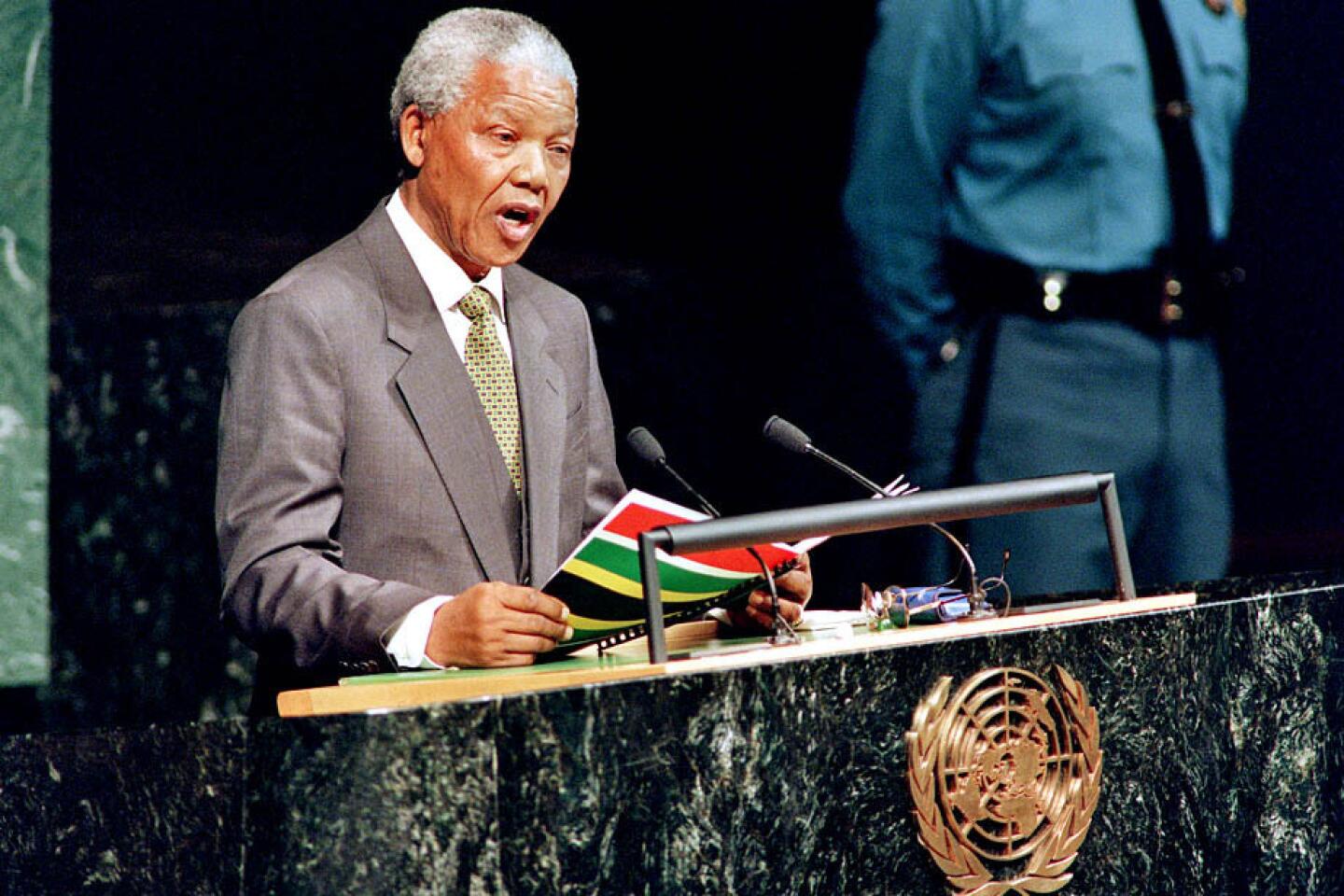

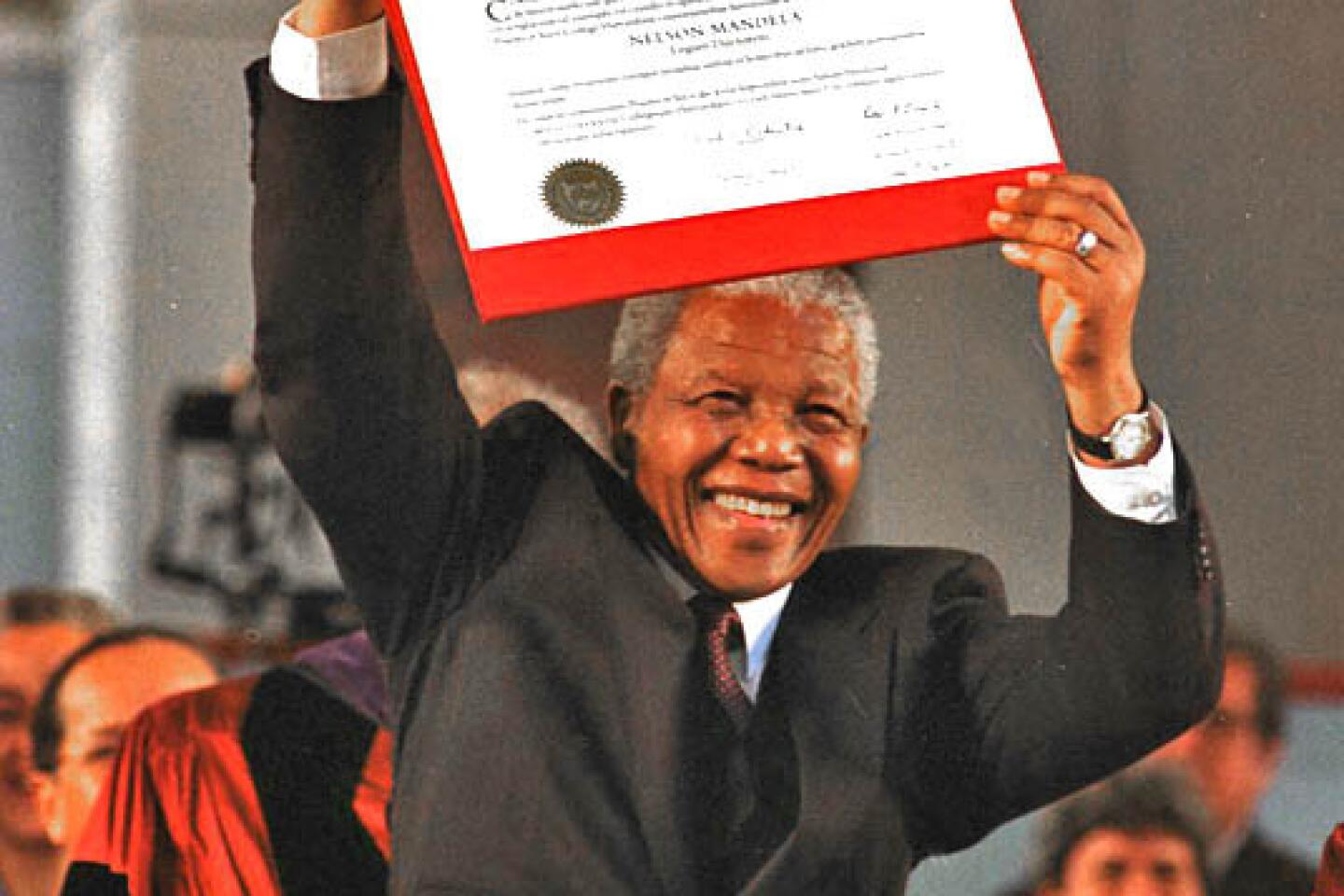

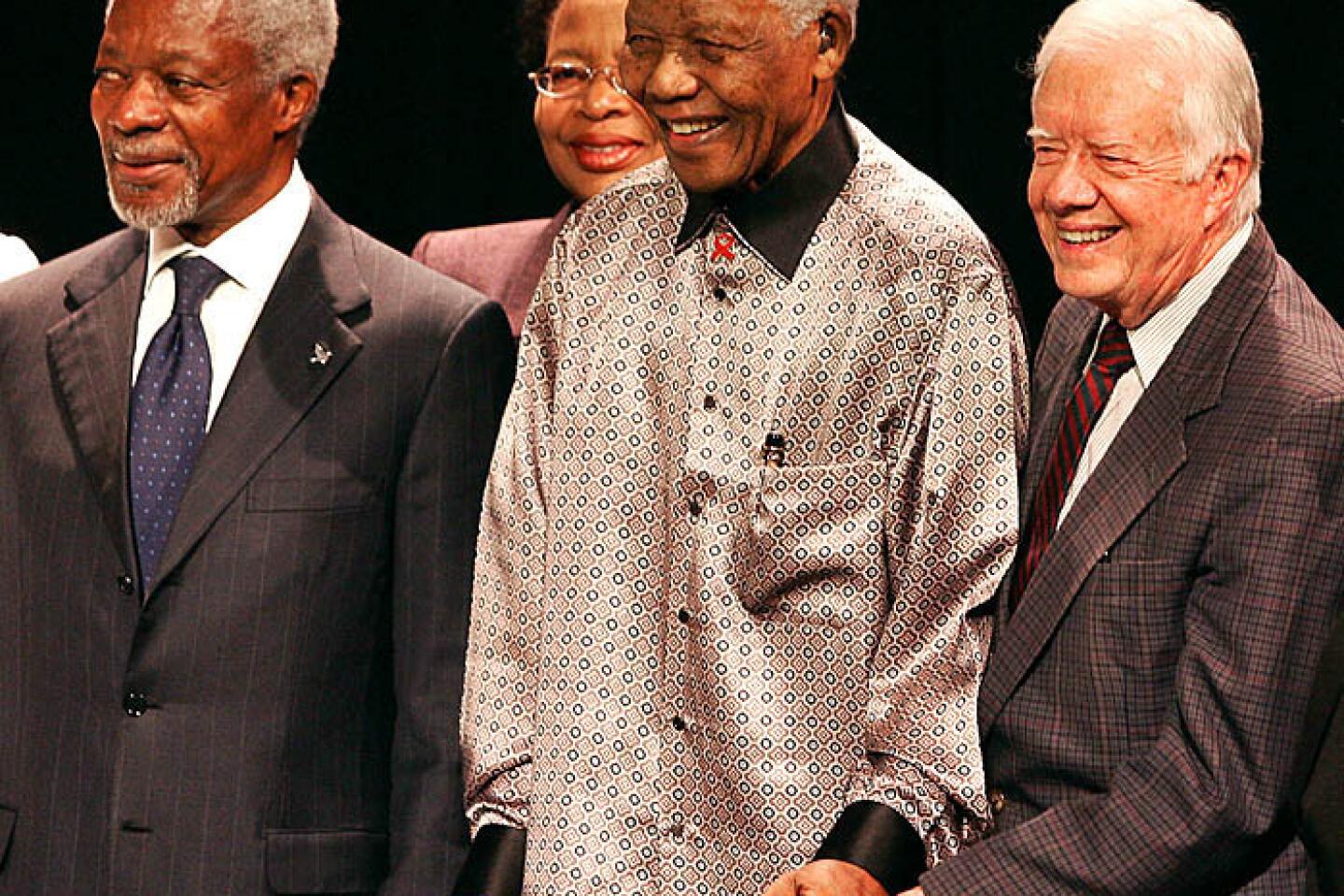

WASHINGTON — His greatest impact was as a moral leader, but Nelson Mandela also left a legacy in diplomacy by helping popularize the use of international sanctions to pressure a government to change its policies.

Since sanctions were imposed in an effort to end apartheid and bring down South Africa’s white-minority government, they have been used hundreds of times, especially by Western countries. President Clinton, who ordered sanctions against Cuba, Libya, Iran and Pakistan, mused near the end of his second term that the United States had become “sanctions-happy.”

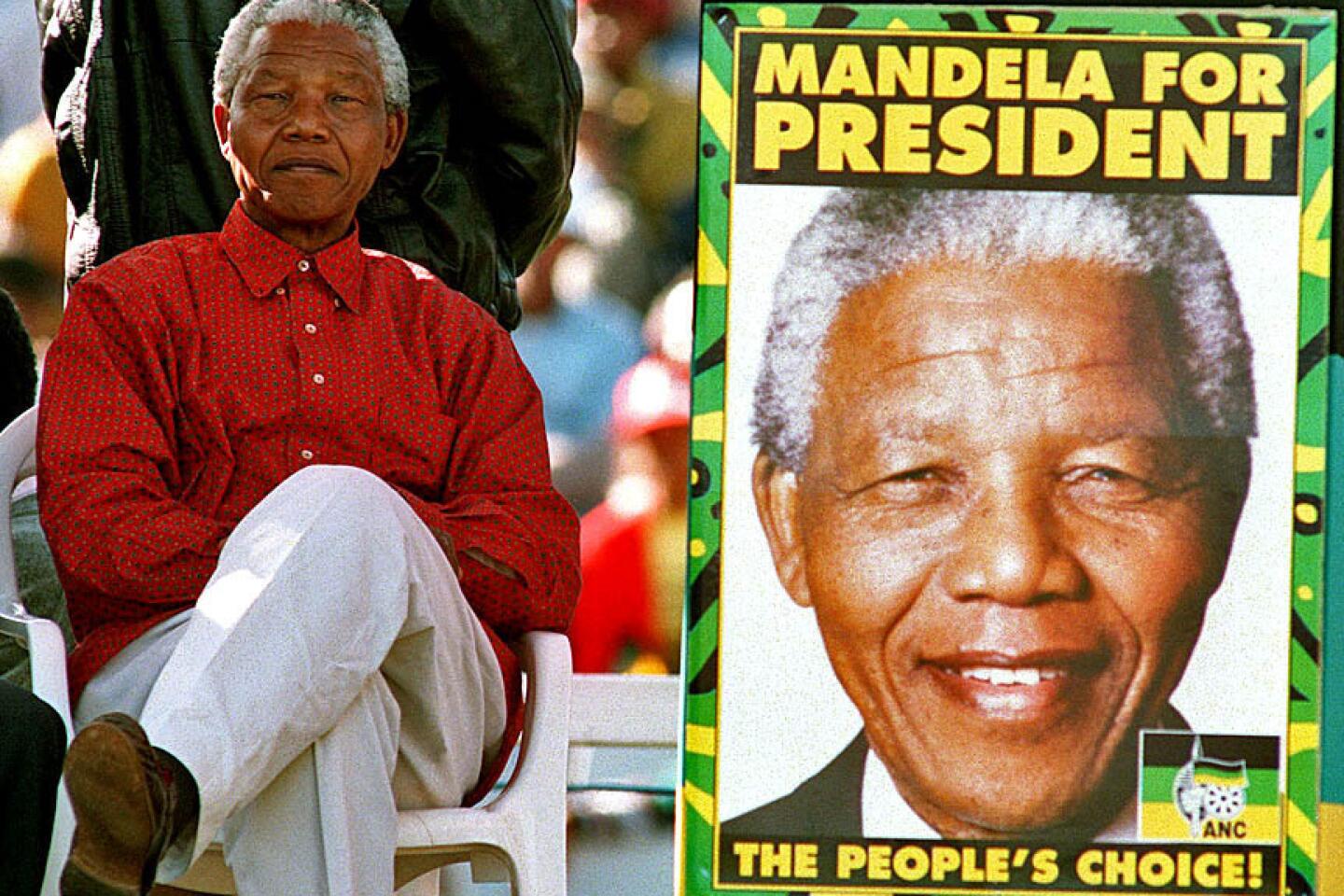

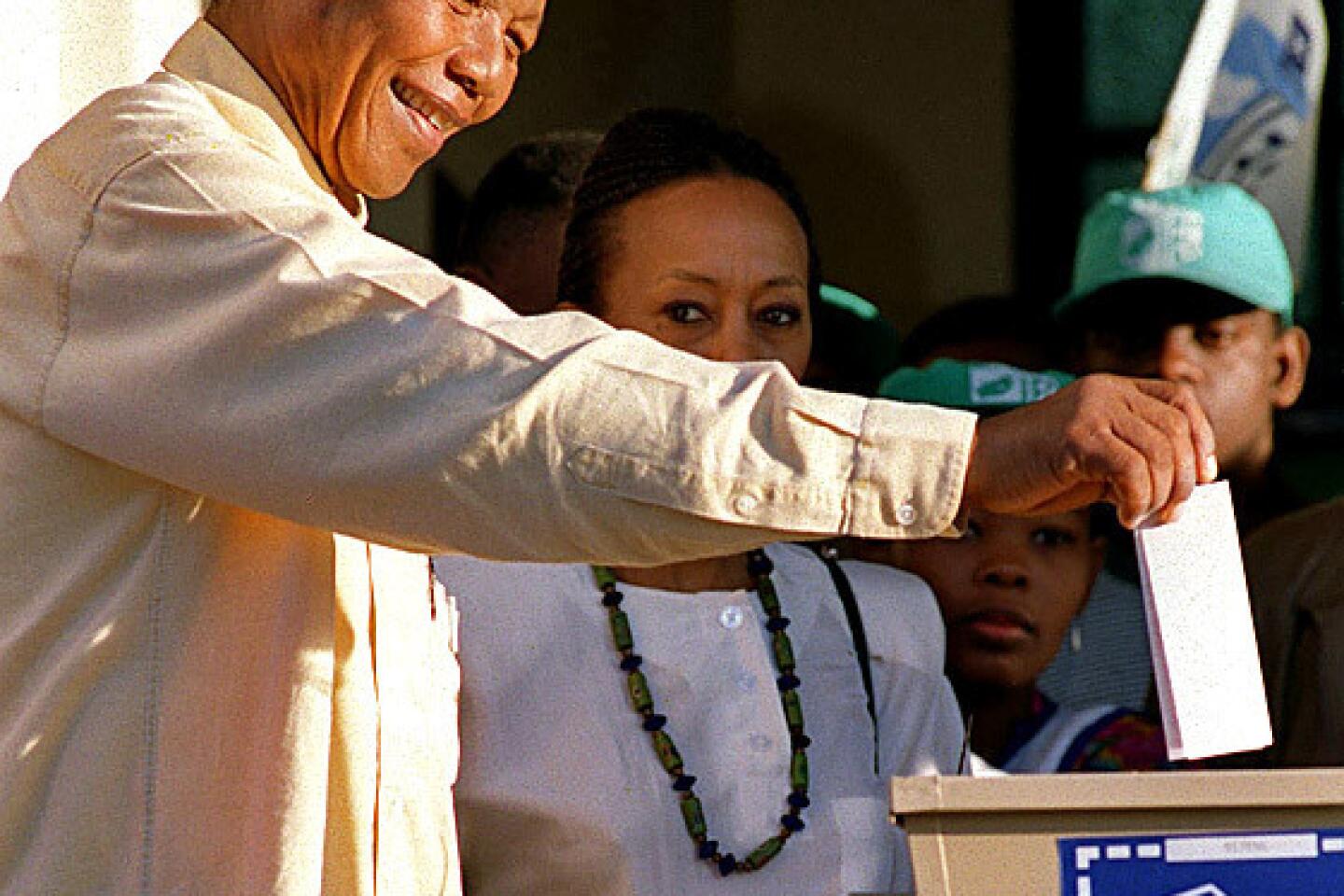

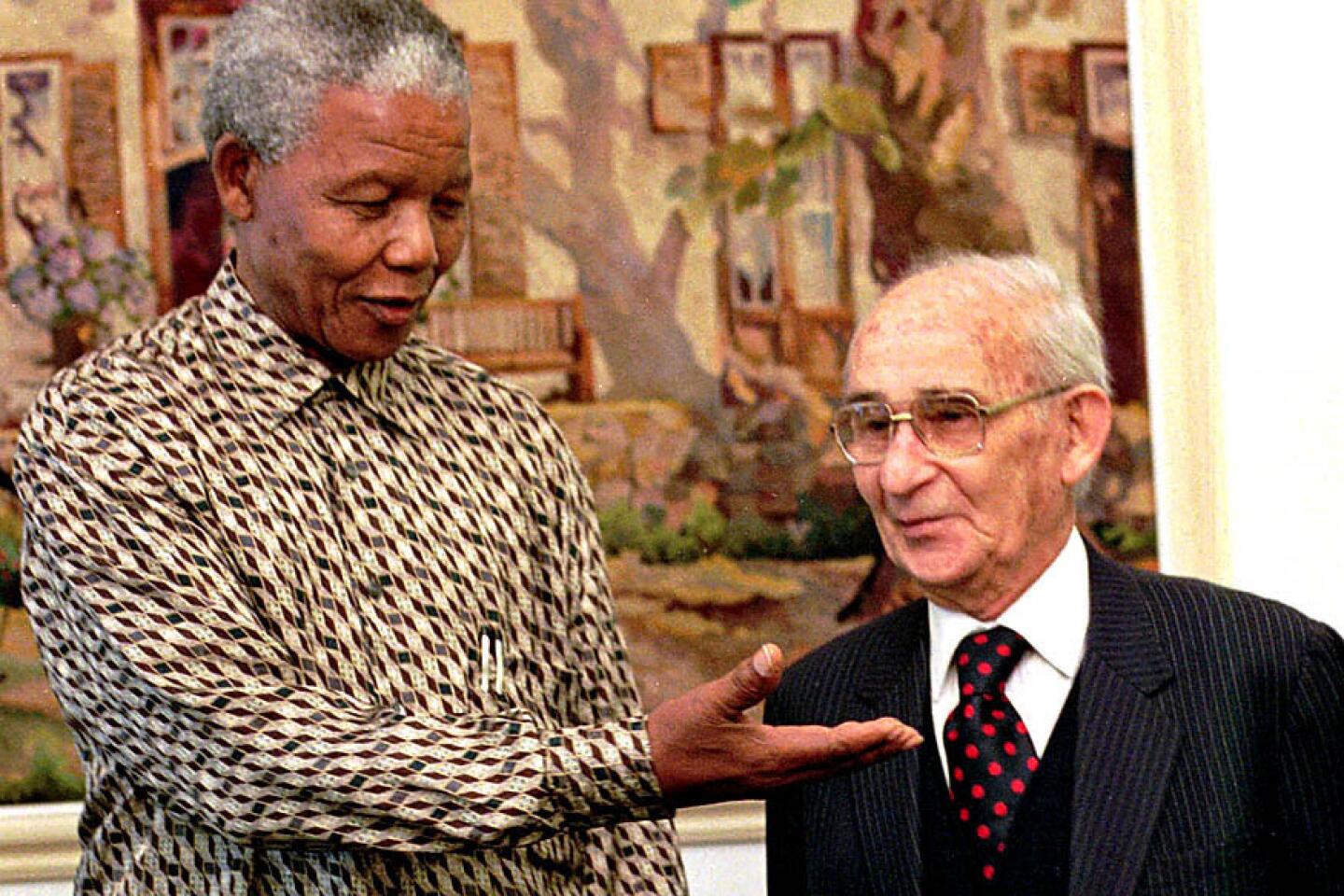

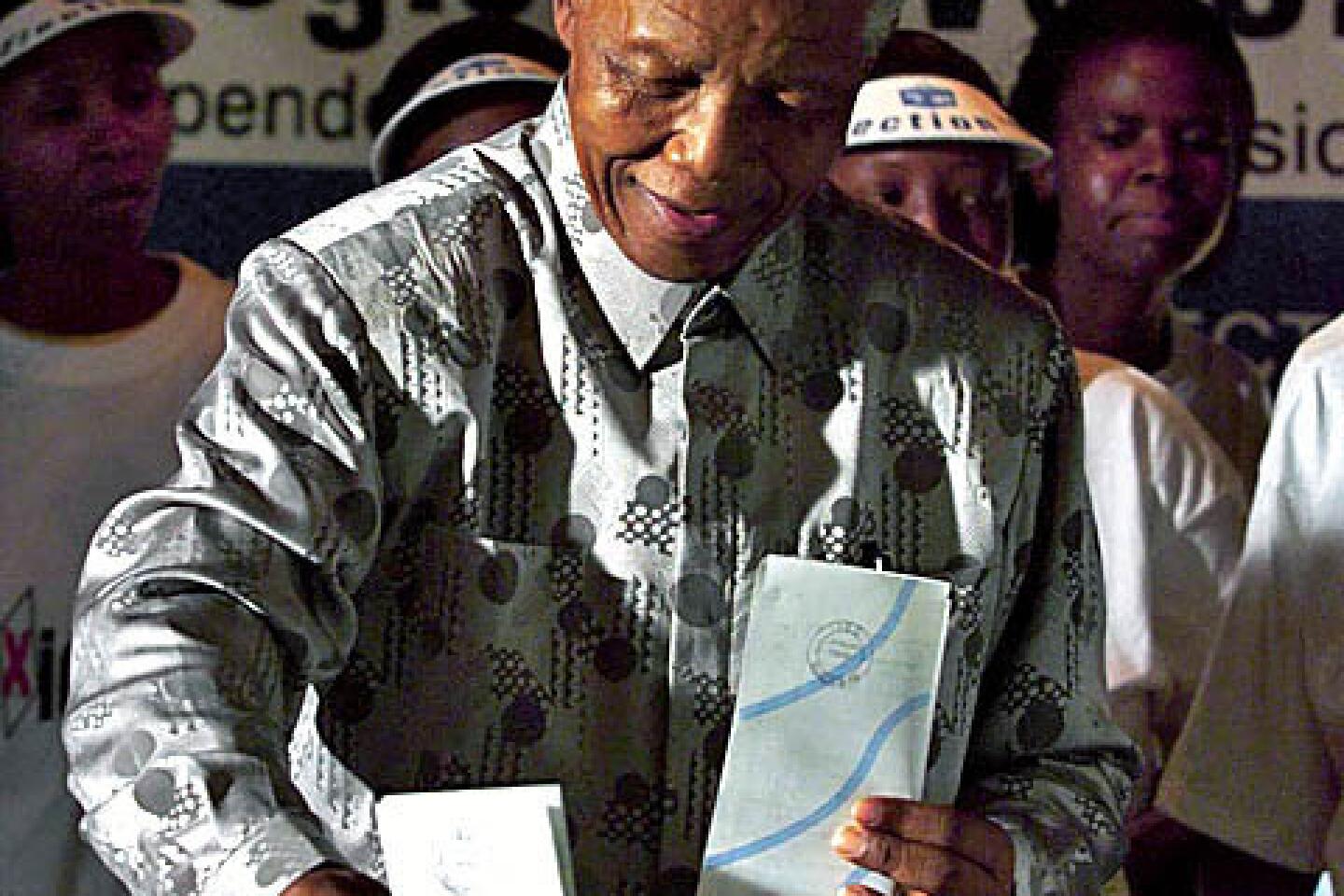

In fact, South Africans and scholars still debate how important sanctions really were in forcing the South African government and President Frederik W. de Klerk to free Mandela and, in 1994, allow the nation’s first democratic elections. In many other cases, sanctions have proved ineffective and more likely to punish ordinary people than the ruling elite.

Authoritarian leaders find ways to evade economic sanctions and remain in power. More than a decade of United Nations sanctions did little to end the standoff with Saddam Hussein that culminated in the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. North Korea has continued to develop its nuclear and missile technology.

Ever-tightening sanctions against Iran have damaged its economy but have not forced it to curb a nuclear program that the West fears is masking an effort to build a bomb.

But their use in South Africa is remembered as the model example. In the view of many, they were employed in a cause pitting good against evil — and good prevailed.

“This was a clear-cut victory and a moral cause — not a messy conflict, but the equivalent of World War II,” said Gary C. Hufbauer, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “It’s everybody’s favorite example.”

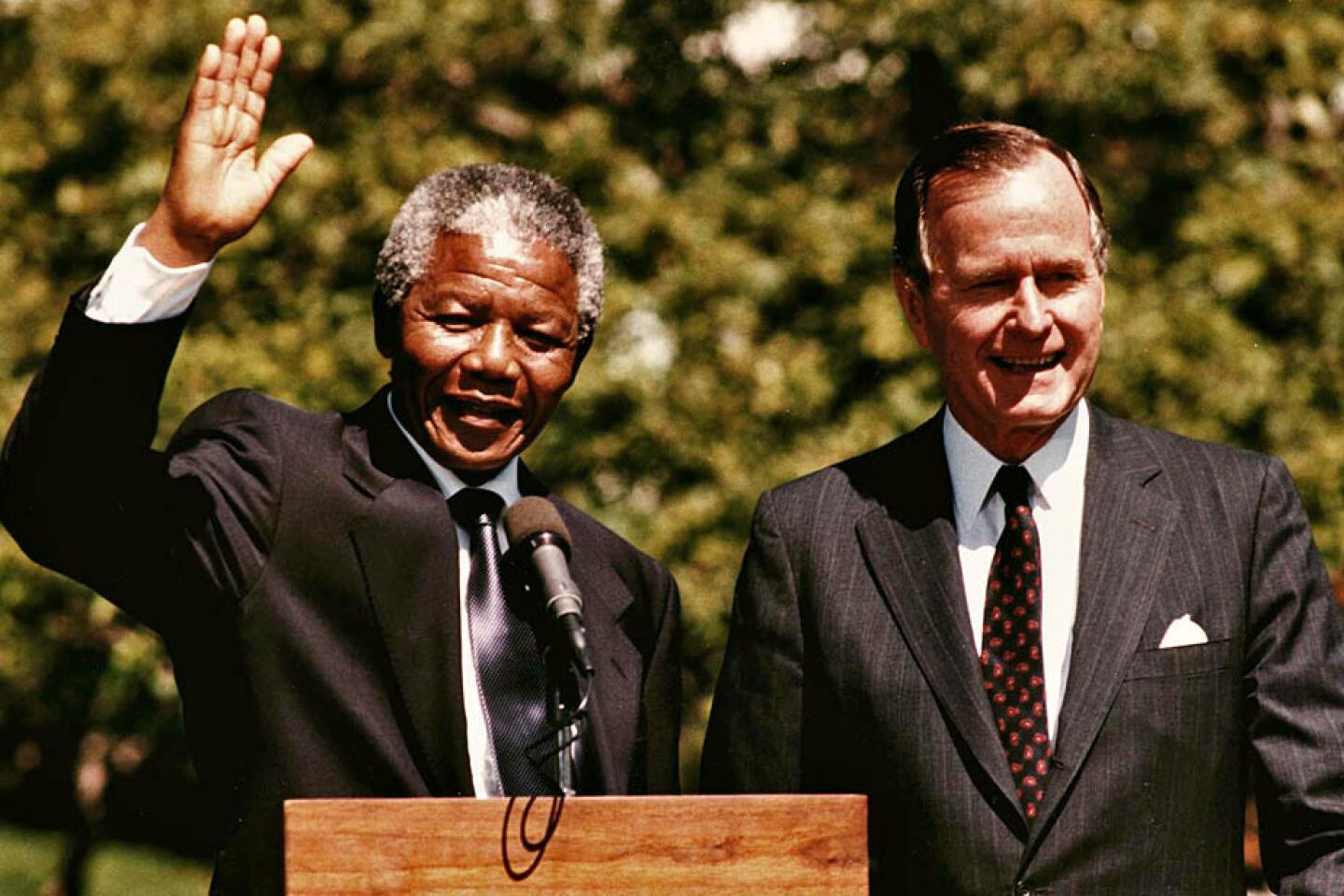

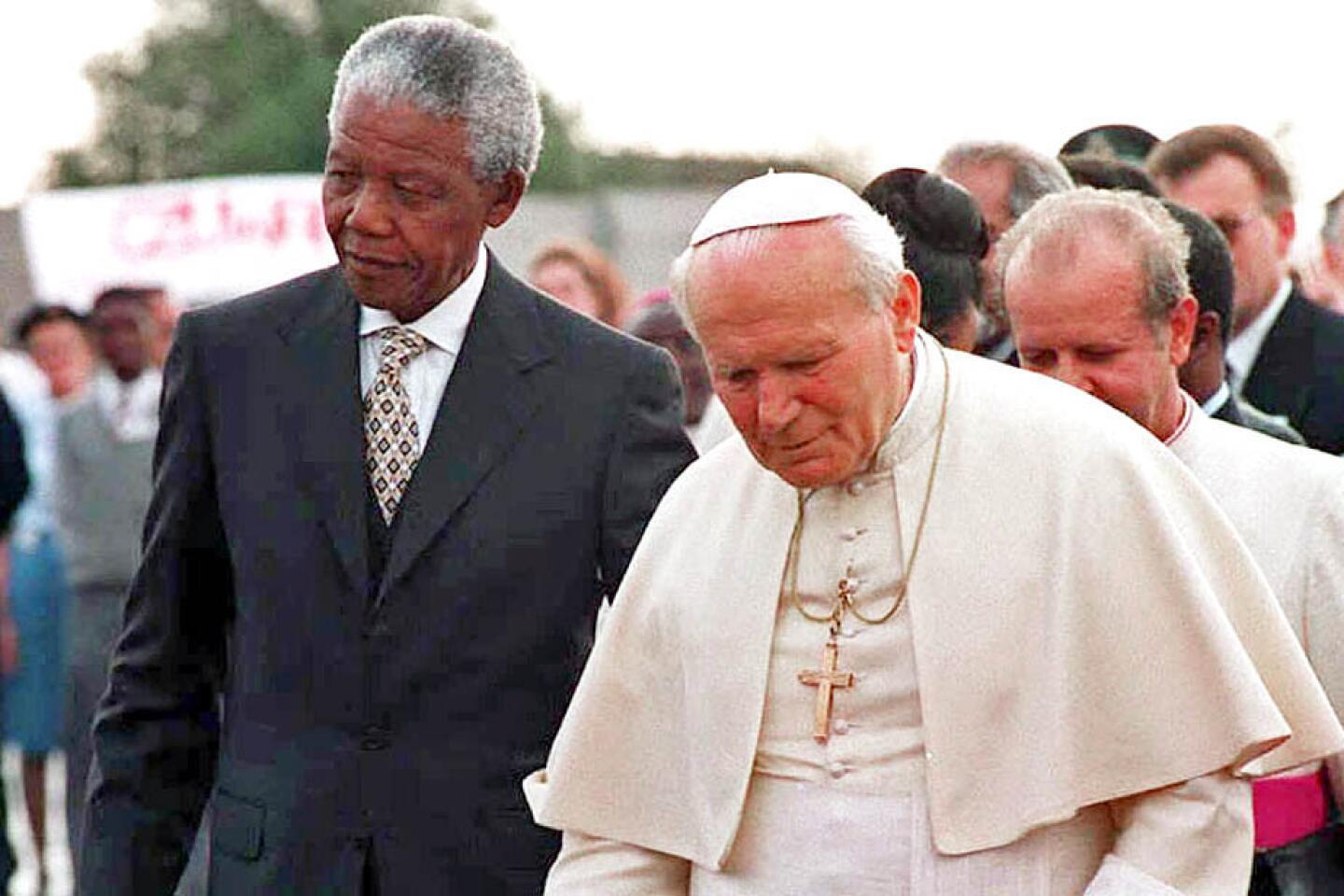

World powers had been punishing South Africa for 17 years before the government took decisive moves to end a system that excluded blacks from power, banned them from jobs and restricted their movements.

In 1977, the United Nations imposed an arms embargo on South Africa in response to a massacre of schoolchildren in the black township of Soweto. Financial penalties began in 1985, when Chase Manhattan Bank, under pressure to sever ties with South Africa, called in its loans.

Other banks in Europe and the United States soon followed suit, and over the next several years, Congress, then state and local governments, halted investment, trade and lending.

Particularly stinging were moves that cut South Africa off from international sports competition, enraging and shaming a country that valued that connection to the outside world.

“Long after this, South Africans would complain, ‘You had no right to cut off cricket,’” said George A. Lopez, a political scientist at Notre Dame University who studied sanctions’ effects for the United Nations. “This really hit national pride.”

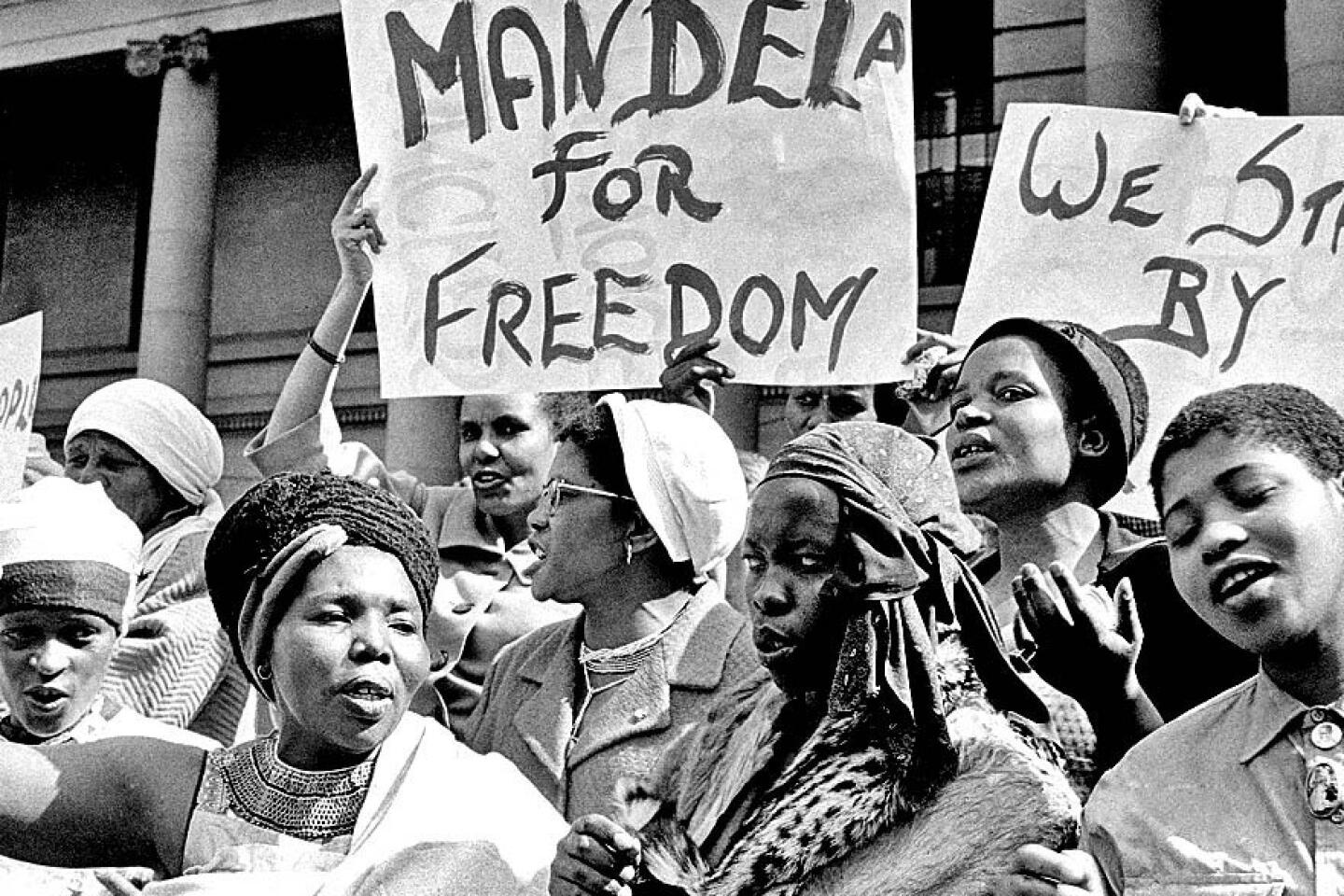

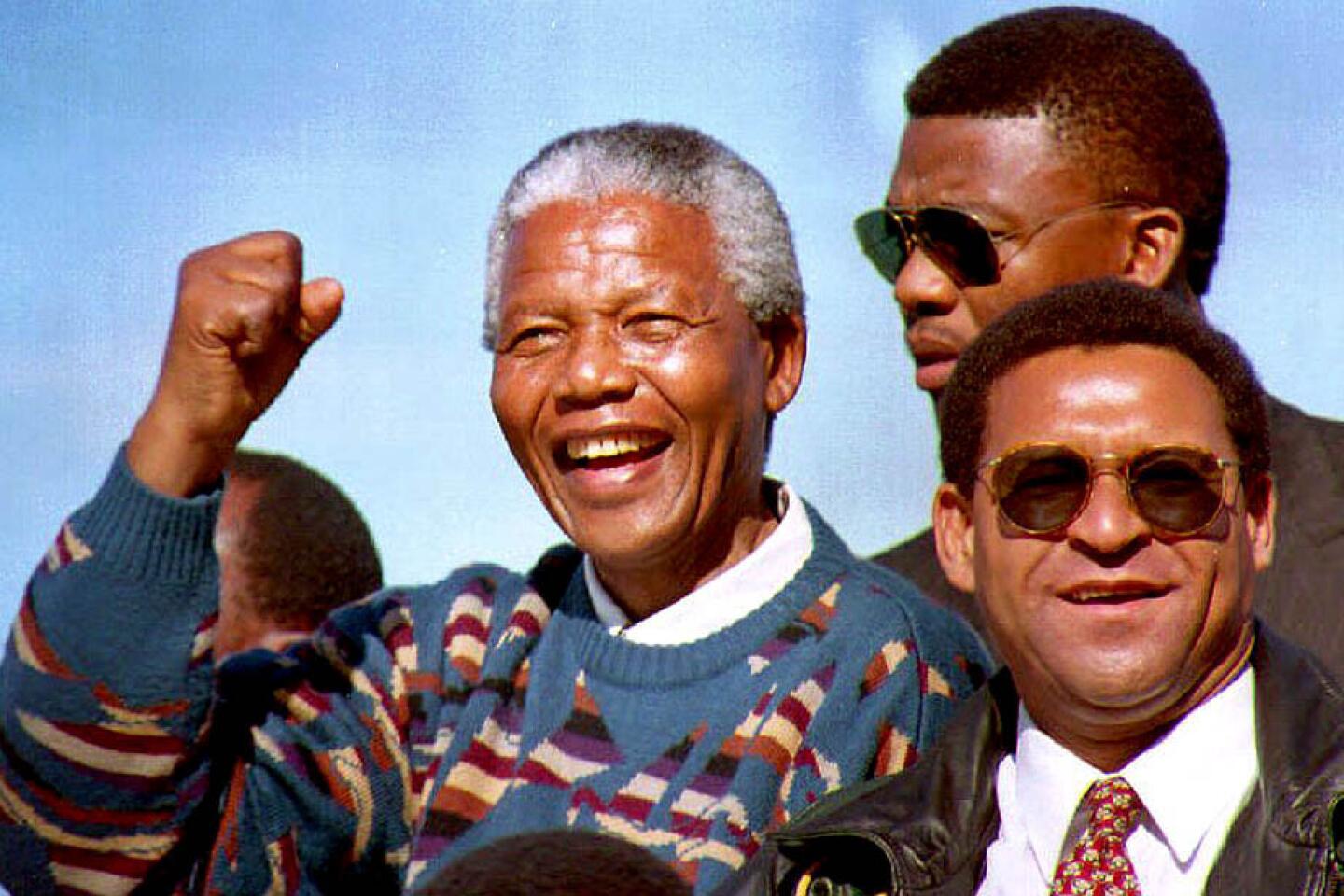

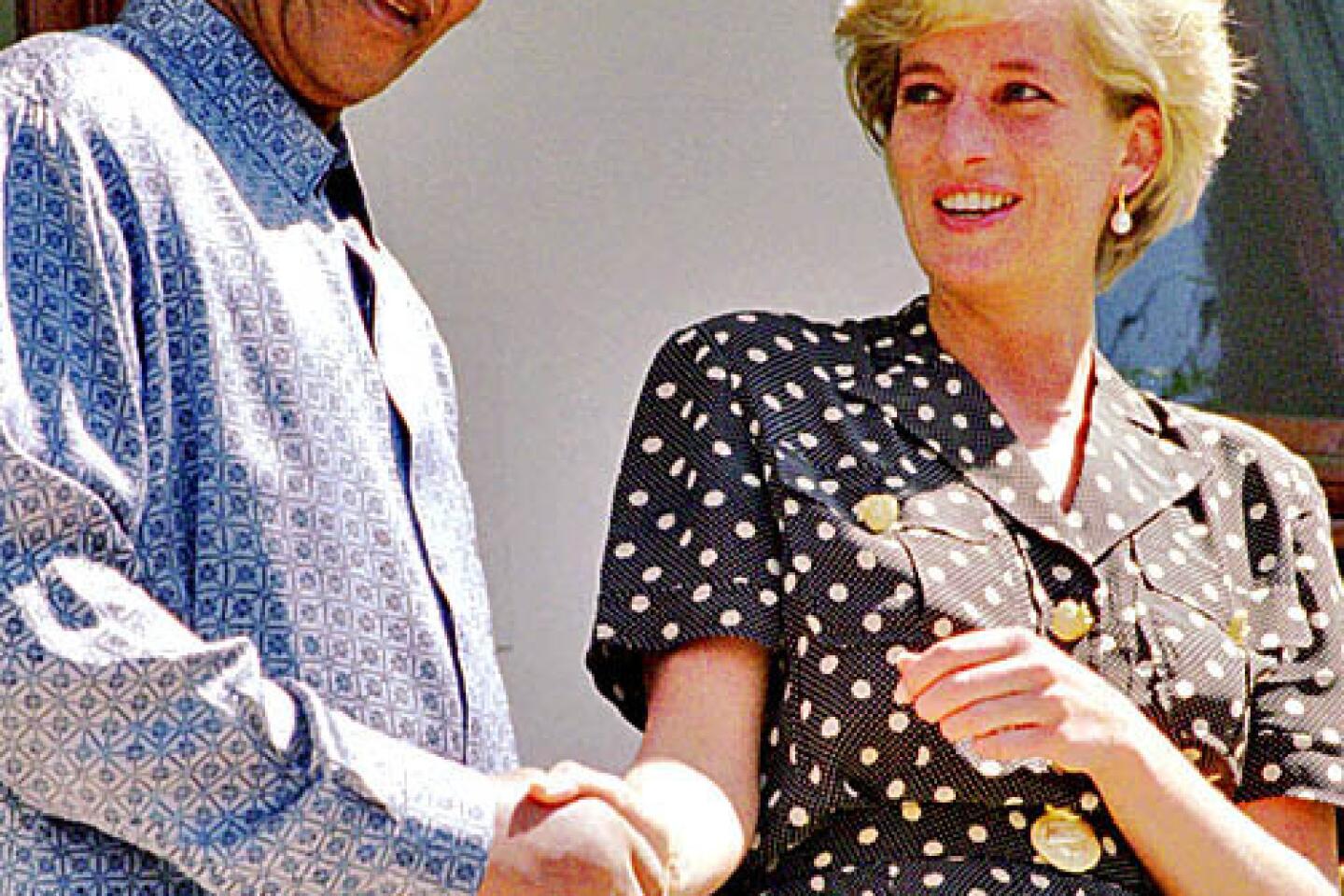

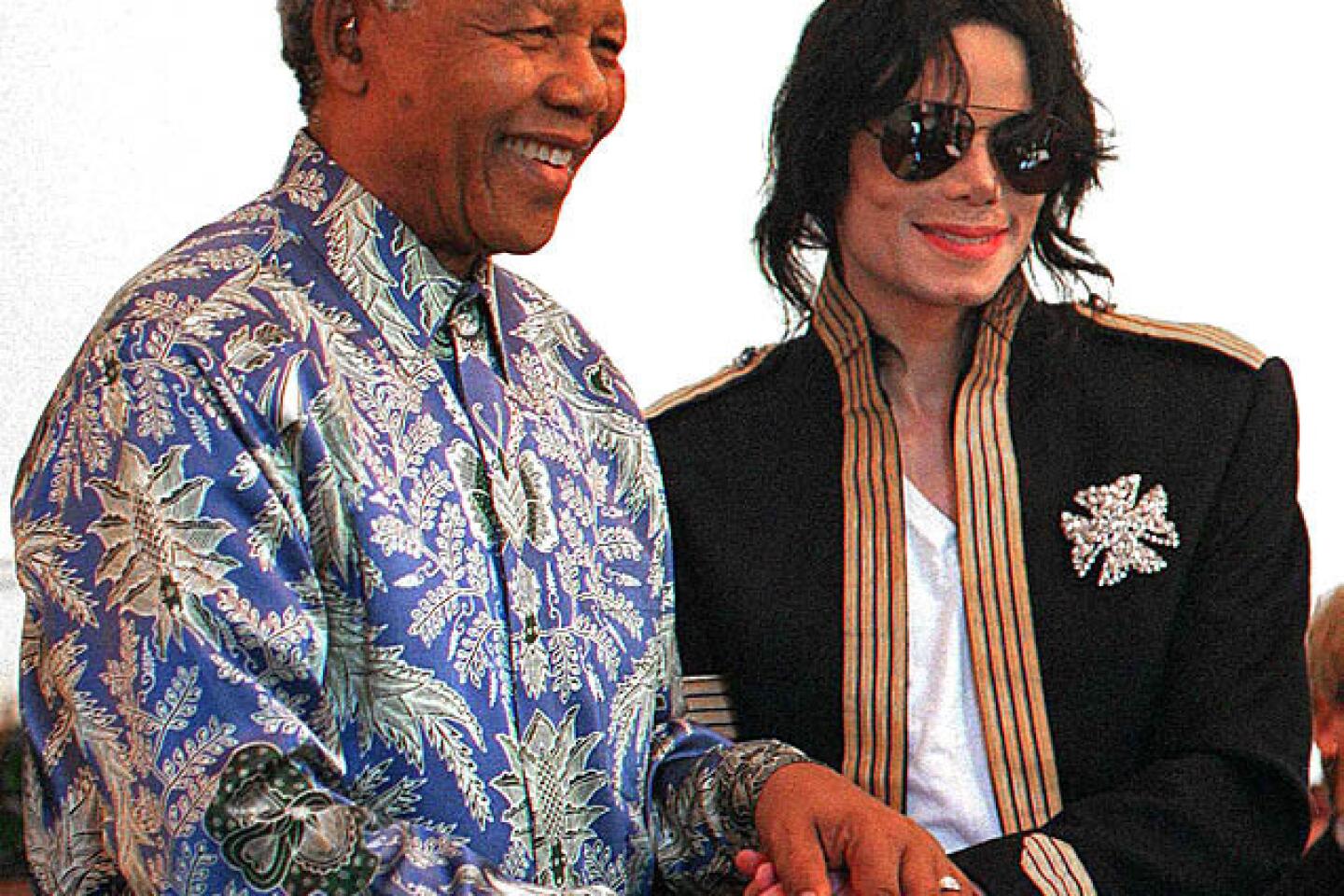

Mandela and his allies sought to promote sanctions as a way to make South Africa an international pariah. Afterward, he described them as a major factor in the outcome.

But many scholars contend that they were less powerful than advertised. Although the sanctions underscored the world’s disapproval, they were imposed piecemeal and often enforced halfheartedly. The West never used the ultimate weapon: an oil embargo that could have devastated the country’s economy.

By Hufbauer’s estimate, sanctions shaved 2% off South Africa’s gross domestic product, far less than the double-digit effects of the sanctions on Iraq and Iran.

“The impact was sizable, but not earthshaking,” he said.

Scholars believe other factors, such as a desire to avoid all-out civil war between whites and the black majority, were more important in bringing about change.

Hufbauer says sanctions’ effectiveness in South Africa is not proof that they can work in the way they are usually used today — to force concessions from authoritarian governments without going to war.

They were effective in South Africa because the leadership cared about the opinion of the outside world, he says.

“The irony is that they worked against South Africa because its leaders cared,” Hufbauer said. “Do Cuba, Iraq and Iran care? No — they view the sanctions as a challenge.”

nge.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.