‘El Chapo’ Guzman’s escape plan: Hidden in plain sight?

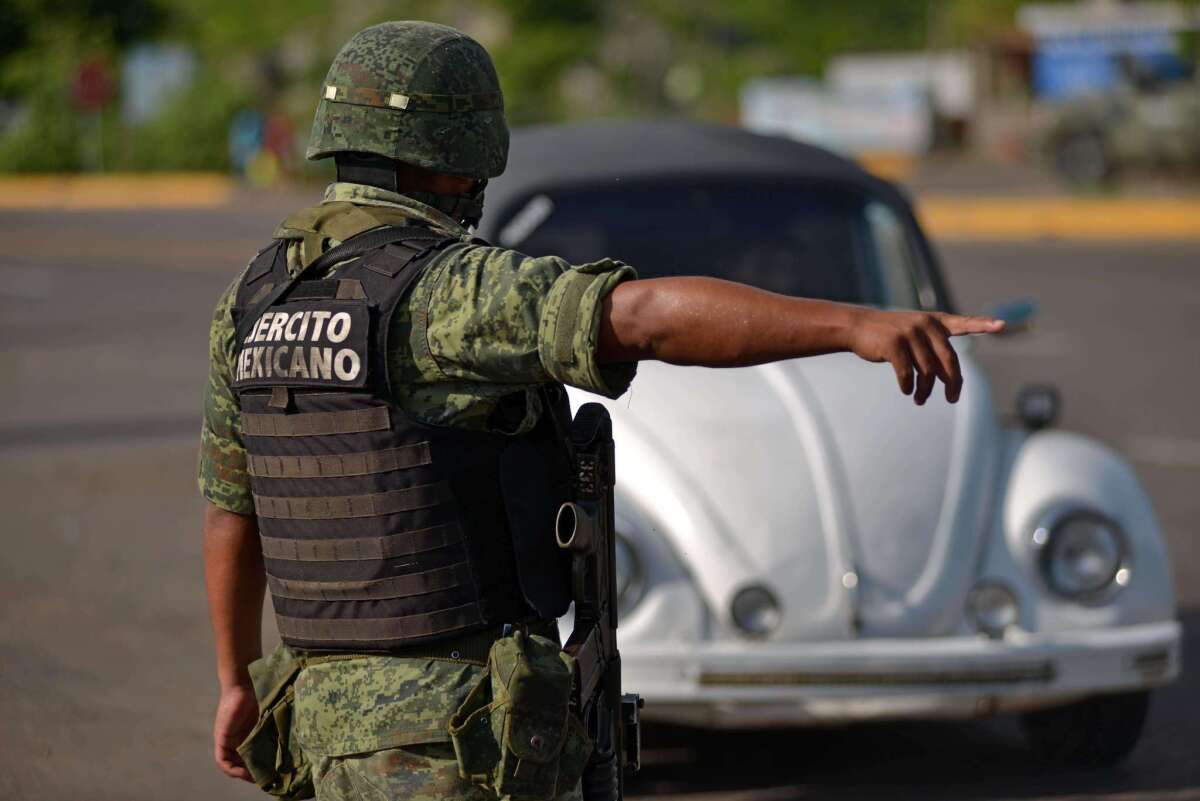

A Mexican soldier stops a vehicle at a checkpoint Wednesday on the highway connecting Badiraguato, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman’s hometown, and Santiago de Los Caballeros, in Sinaloa state, Mexico.

- Share via

Reporting from Mexico City — As Mexicans debated the brazen prison breakout of drug kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman on Tuesday, it became increasingly apparent that there had been signs for months that something was brewing at the maximum-security Altiplano prison where he was held.

The tunnel that Guzman used to make his escape ended up in an unfinished house in the middle of an empty field. The nearest residents said workers started building the house out of the blue and without permits about 10 months ago.

Guzman had reportedly petitioned the national human rights commission to prevent surveillance cameras in his shower, claiming such intrusion was a violation of his rights. It is in the shower where the opening of the tunnel was dug.

Guzman also had maps of the prison, Interior Minister Miguel Angel Osorio Chong said.

A Twitter account that purports to belong to one of Guzman’s sons predicted his escape months ago, adding later, “Good things come to those who wait.”

As such details emerged, Mexicans expressed outrage, disbelief and demands for punishment of top officials.

Meanwhile, President Enrique Peña Nieto, who after Guzman’s capture last year had said losing him again would be “unforgivable,” continued a state visit in Paris. On Wednesday, he was sampling cuisine, his office said.

From talk shows to social media networks and YouTube, Guzman, head of the powerful Sinaloa Cartel, was being praised, admired, reviled and condemned. It seemed almost equal amounts of condemnation were hurled at the government.

Authorities paint a picture of badly bungled handling of Guzman’s security and acknowledge corrupt officials played a major role. So far, three prison officials have been fired, the government said, but Osorio Chong, the nation’s top law enforcement officer, refused to resign.

While Guzman was still behind bars, the U.S. government had expressed concern that he would flee and said it wanted to have him extradited. However, it is unclear a formal petition was ever filed. Extradition “has been a subject of ongoing discussions between the United States and Mexico,” a Justice Department spokesman said.

Mexico had used a national-sovereignty argument, saying it was confident it could prosecute the notorious criminal.

Osorio Chong denied U.S. news reports that the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration specifically warned Mexican authorities about two escape attempts in the nearly 17 months Guzman was held. He had previously broken out of a maximum-security prison in 2001, after his capture in Guatemala in 1993 and extradition.

If Guzman was a folkloric figure during his 13 years on the lam, that stature will only grow now. Already, Mexicans were penning narco-corridos, the bouncy songs that recount the exploits of major traffickers, about the escape.

“Why are they looking for me / If I am the king of the kings / That’s been confirmed,” goes one by someone calling himself Regulo Rubido and posted on YouTube.

“I am the king of the kings, I can assure you / One year later I am braver and more determined / The king of kings is active!”

From another: “Well he escaped through another tunnel from the Altiplano / and now they’ll have to involve the government Americano.”

Mexicans were by turns chagrined, outraged, flabbergasted and disbelieving, both about the escape itself, how the government could let it happen and that there is not more fallout.

Even media normally friendly to Peña Nieto were angry.

“What does it take for someone to resign in this country?” morning talk show host Victor Trujillo (better known as El Brozo, a green-wigged clown). “Mexico today is much less safe than it was on Friday.”

Follow @TracyKWilkinson on Twitter for more news from Latin America.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.