As hearings for Sept. 11 suspects resume, neither side seems in a hurry to get to trial

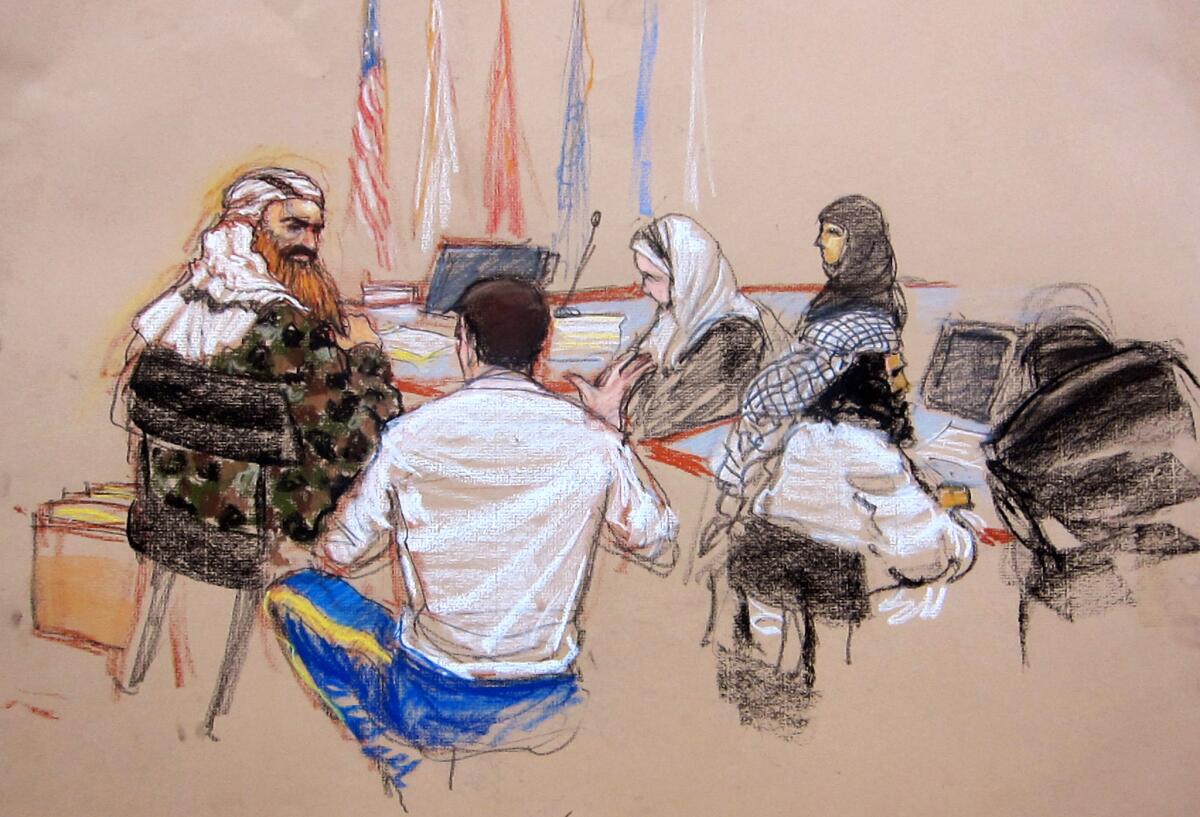

In this courtroom sketch, self-proclaimed terrorist mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, left, confers with his lawyer Army Capt. Jason Wright, second from left, at the Guantanamo Bay U.S. Naval Base in Cuba, Monday, Feb. 11, 2013.

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — On Monday morning, a U.S. Army colonel in judicial black robes will take his seat on a high dais for another round of pretrial hearings in the most secure American courtroom anywhere — on the U.S. naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and four other accused Sept. 11 plotters will sit at the end of long defense tables, flanked by teams of attorneys. To their right, military and federal prosecutors will gather.

Eight months have elapsed since pretrial hearings began in this high-profile case, seen as the biggest prize in the battle against Al Qaeda. More than four years have passed since the men were first arraigned on potential death penalty charges. It has been 13 years since they were captured.

Yet they are nowhere near a trial date.

In the meantime, other accused terrorists, including the self-proclaimed 20th Sept. 11 hijacker, Zacarias Moussaoui and Boston bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, have been tried, convicted and sentenced in U.S. courts.

Though the complex military and legal bureaucracy is partly to blame, delays in delivering justice at the Guantanamo military tribunal also stem from something else: Neither side seems all that eager to go to trial.

Federal prosecutors are concerned about airing secret government programs or revealing embarrassing details about torture, especially in a trial that would be watched closely by much of the world.

Attorneys for the accused know that the sooner a trial ends, the sooner their clients probably could be put to death in a case overseen by a U.S. army judge and a jury of U.S. soldiers.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

U.S. officials insist, however, that they remain committed to reaching a judgment in the case and that despite all the setbacks, progress has been made.

Prosecutors have turned over more than 300,000 pages of documents to the defense, 189 pretrial motions have been briefed and argued and 23 witnesses have been questioned in more than 65 hours of testimony. In addition, 190 exhibits and 102 declarations have been filed in the case.

“These preliminary trial sessions are an indispensable part of our justice system,” said chief prosecutor Brig. Gen. Mark Martins. “We will build upon this work as we methodically move the case toward trial.”

But prosecutors and defense lawyers also spent much of this year haggling over a “memorandum of understanding” about how the defense will handle highly classified material.

Defense attorneys blame the delays on the government’s obsession with secrecy, particularly when it comes to allegations of torture against the five men.

“There’s a fundamental tension between secrecy and a fair trial,” David Nevin, Mohammed’s chief defense lawyer, said. “They claim ‘national security,’ which makes little sense where the torture program has been outlawed.

“More likely, they want to keep the information about the torturers under wraps since the inconvenient truth is that those people [the government] committed serious criminal offenses under domestic and international law.

“Either way,” he said, “secrecy is inconsistent with due process, a fair trial and the right to counsel and constitutional rights, which, among many other requirements, necessarily involve a high degree of openness about government behavior.... I wouldn’t be at all surprised to hear that the government has concluded that that tension can’t be resolved — and really needn’t be.”

But some suspect the defense is not really in that much of a rush either.

Much of the government’s evidence in the case appears overwhelmingly against the suspects, including Mohammed’s admissions about masterminding the Sept.11 plot and other terrorism schemes. A guilty verdict even after all these years seems almost certain.

The defense may have one final card to play.

In many past terrorism trials in U.S. federal courts, juries have been reluctant to hand down a death sentence for fear it would make the defendant a martyr and inspire others. Even Moussaoui begged to be put to death but was given life instead.

But a military judge and jury might be less likely to reach such a decision.

Twitter: @RickSerranoLAT

ALSO

Gov. Brown’s link between climate change and wildfires is unsupported, fire experts say

‘Larrymania’ reality star is now in real trouble -- in small-town South Carolina

‘El Chapo’ is wounded but not caught as Mexico’s military roars into terrified villages

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.