Mexico’s disaster bonds were meant to provide quick cash after hurricanes and earthquakes. But it often hasn’t worked out that way

- Share via

Hurricane Odile churned toward the western coast of Mexico on Sept. 14, 2014, a Category 4 storm with winds powerful enough to flatten homes, bend lampposts and punch windows out of luxury high-rises.

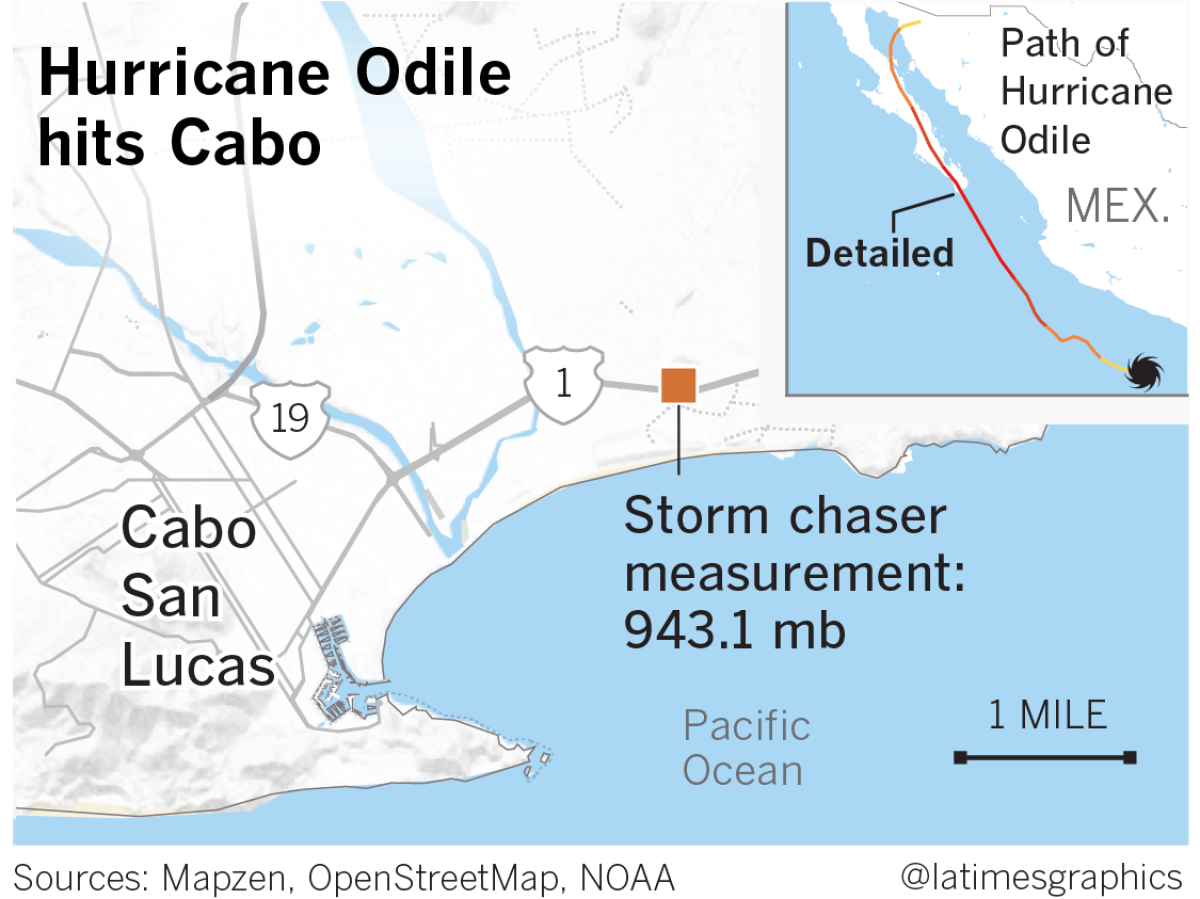

Officials across southern Baja braced for impact, shuttering schools, grounding flights and opening emergency shelters. In the resort city of Cabo San Lucas, where the storm would make landfall late that night, police officers raced through drenched and blustery streets with megaphones, warning everyone remaining to leave.

More than a thousand miles away in Mexico City, federal government officials watched nervously, hoping their recent investments in an unusual financial scheme would help cover the damage.

With the help of Wall Street and the World Bank, Mexico had issued a series of complex insurance securities called catastrophe bonds, which promise quick payouts when powerful storms or earthquakes strike.

Known as “cat bonds,” they were designed for events just like Odile — a storm U.S. officials would describe as the "strongest hurricane to make landfall in the satellite era in the state of Baja California Sur."

Indeed, from all reports the government had seen, including from the U.S. National Hurricane Center, they were going to collect $50 million.

And they might have, had it not been for a storm chaser from Los Angeles, whose atmospheric pressure readings from a beachfront hotel would upend the entire system, denying the battered government any payout, while keeping the funds secure for investors through a shell company in the Cayman Islands.

A year later, the same thrill-seeker’s data would help lower another projected payout, when Hurricane Patricia, the most powerful storm ever recorded in the Western Hemisphere, hit the western state of Jalisco.

Combined, the incidents prevented Mexico from collecting tens of millions in recovery funds and exposed fissures in this arcane yet booming financial market — today worth $90 billion.

The market is dominated by private insurance companies, but institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have promoted it as a potential lifeline for the world’s neediest countries, many of which also happen to be the most vulnerable to natural disasters.

An examination of Mexico’s experience by Columbia Journalism Investigations and the Los Angeles Times shows the bond program has often failed to deliver. Investors have seen promising returns from taxpayer-funded premiums, but Mexico has suffered a barrage of storms and quakes that don’t meet the technical parameters required for a payout, leaving the government to pick up the bill.

The investigation, stretching from New York to Hollywood, the Caribbean and rural Mexico, is based on thousands of pages of financial documents, interviews with former government officials and industry insiders and dozens of internal documents from the Paradise Papers leak. Those records were obtained by the German newspaper Sueddeutsche Zeitung and shared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Among its findings:

- The data used to determine whether Mexico receives payouts from the bonds have at times come from nongovernmental sources, leaving the system opaque and open to manipulation.

- Although bond payouts were designed to provide Mexico with immediate financial relief, it can take months to determine whether the country is eligible — and longer to send the money. More than three months passed before a payout decision was made following Hurricanes Patricia and Odile.

- While the bonds were designed to cover the biggest disasters, the country’s most destructive storms and quakes have not always triggered payouts — including a 7.1 earthquake last fall in Mexico City that killed 369 people.

- Even when payments have been made, Mexican disaster officials have no mandate to spend it on damage from the triggering event, and the government does not specify where that money goes.

Investors, government officials and others argue the bonds serve an important role in a country’s disaster-planning strategy, and Mexico had all the tools to design its bonds in the nation’s best interest.

Cat bonds have helped “build a better financial shield in Mexico and other countries, for the benefit of citizens,” a spokesman for the country’s Secretariat of Finance and Public Credit said in a statement.

“This is a sophisticated country, with a sophisticated understanding of the capital market, of the risk market,” said Alex Klopfer, a World Bank spokeswoman in Washington. “At the end of the day, the sovereign has all the information to make a decision.”

The World Bank has highlighted and promoted Mexico’s experience as other nations follow suit, including Colombia, Chile and Peru, who announced in January they were joining Mexico on a new $1.4-billion cat bond, the largest government-sponsored deal to date.

Cat bonds emerged in the mid-1990s, after Hurricane Andrew ravaged the Florida coast and bankrupted nearly a dozen insurance companies, which didn’t have the money to cover such a massive storm.

Fearful of being overwhelmed by similar and even bigger catastrophes, insurance and reinsurance companies turned to the capital markets, flush with deep-pocketed investors such as hedge funds and money managers.

The bonds they created were often held by shell companies in offshore tax havens, offering high returns in the form of premium payments, from the issuer. Total returns from cat bonds, for years, easily beat those offered by the S&P 500 index. And because they are hedged on natural disasters, not economic indicators, they are less prone to the vagaries of the global economy.

They carry risk, though: If, during the bond’s life, a natural disaster of a certain, predetermined size or financial toll triggered the bond, investors lost some or all of their money and the issuer — the insurance company, or government — got the payout.

Analysts and leaders at the World Bank saw potential in the burgeoning market for poorer, developing nations that lacked robust insurance networks for storms and other disasters.

Mexico became the test case.

Susceptible to an array of tropical storms, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, floods and droughts, Mexico had for years struggled to recover financially from its most crippling events. The government created a special disaster fund in the late 1990s to help stabilize the budget, but its funding was inconsistent. In 2005, for instance, the fund took in just $47 million, yet faced $722 million in expenses after an especially ruthless hurricane season.

The next year, with help from Swiss Re, a global reinsurer, the government launched its first cat bond, worth $160 million. A spokesman for Swiss Re said, in an email, that the company has long promoted cat bonds and other forms of “risk transfer” as part of a comprehensive approach to risk management.

An executive at AIR Worldwide, a risk modeling firm that worked on the deal, hailed it as “a landmark transaction that can be used as a model for catastrophe loss protection for developing countries in Latin America and around the world.”

But under the terms of the bond, only earthquakes in three slivers of the country were covered, and to trigger a payout they had to register a magnitude of at least 7.5 in one section, or 8.0 in the other two. Moreover, the bond provided no cover for hurricanes.

As the government looked for ways to strengthen future bonds, the World Bank offered a potential solution. The bank had recently helped a group of Caribbean countries create an innovative insurance pool, and now, representatives told Mexico, it was ready to tackle cat bonds through an ambitious program that would spread risk to investors by uniting multiple countries into one collective bond, according to Salvador Perez, an insurance expert who joined the country’s Ministry of Finance in 2007.

They called the program MultiCat, and its inaugural members were to include Greece, Singapore, Colombia and Chile.

Within months, all but Mexico had dropped out. Some decided it was too expensive; others felt they lacked the technical capacity to negotiate an acceptable deal, Perez said. (Klopfer, the World Bank spokeswoman, declined to comment.)

By early 2009, with the World Bank’s help, it had a new deal in place. The $290-million bond, called MultiCat Mexico, expanded the earthquake coverage and incorporated hurricanes along both coasts.

The bond was again designed by Swiss Re, but this time with additional help from Goldman Sachs, one of many U.S. financial companies jumping into the industry.

When that bond expired, in 2012, a new $315-million deal was launched, further expanding the coverage and creating tiered payouts.

It seemed straightforward until Odile hit southern Baja in September 2014.

Outside the Holiday Inn Express in Cabo San Lucas, brutal winds pounded the walls and blew doors out of their frames. Inside, ceiling panels crashed to the ground, while terrified guests scrambled for safety.

Crouched behind an abandoned reception desk and filming the destruction was Josh Morgerman, a self-styled storm chaser from West Hollywood.

Morgerman, now 48, started his career working in the film industry after studying history at Harvard University. In 1999, he co-founded a branding and advertising agency, called Symblaze, whose clients included Vodafone, Google and the cities of West Hollywood and Palm Springs. Unable to shake a childhood obsession with hurricanes, he began chasing storms.

The day before Odile made landfall, Morgerman flew to Cabo San Lucas and set up his equipment: two camcorders, an iPad, a mobile phone, a car charger, a laptop and two Kestrel 4500s — cellphone-shaped barometers designed to record the change in atmospheric pressure as the eye of a storm passed. He slung one of the Kestrels around his neck and left the other in his third-floor hotel bathroom — the safest room in a hurricane.

Pressure readings gathered in the eye of a hurricane are important indicators of a storm’s strength — in general, the lower the number, the stronger the storm.

As Odile’s eye approached between 9 and 11:08 p.m., the pressure outside dropped 40 millibars, bottoming out at 943.1 millibars, according to Morgerman’s readings. That was more than 21 millibars higher than a U.S. Air Force Reserve reconnaissance plane had recorded hours earlier, and 13 millibars higher than a reading the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported at 11 p.m.

Morgerman sent his readings to the U.S. National Hurricane Center, which collects storm information from a variety of sources — government aircraft, satellites, ships, oil rigs, local weather stations and on-the-ground reports. The center uses the data to produce storm reports, widely considered an official statement on the severity and size of hurricanes in the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific.

Those storm reports also determine payouts in the Mexican bonds.

“I’ve always been uncomfortable with that, knowing what the limitations are in some of these determinations,” said James Franklin, former director of the center’s hurricane specialist unit.

Franklin, who retired last June, said he avoided becoming familiar with the bonds so that he could “evaluate the meteorological data without knowing what any financial consequences might be.”

The bond was designed to deliver a 100% payout if the pressure was 920 millibars or below, and a 50% payout if under 932 millibars. After Odile hit, investors and industry insiders watched developments closely, and media commentators predicted a $50-million payout based on an initial hurricane center report of 930 millibars.

In the Cayman Islands, an attorney at Appleby, the law firm managing Mexico’s shell company — and the firm at the center of the Paradise Papers leak — shot an email off to a colleague at Kane Holdings Limited, which specialized in cat bond operations.

“Anything we should be doing or considering at this point …?” wrote the lawyer, Julian Black.

The firm needed to wait and see if it had officially triggered a payout “and work from there,” the colleague responded, according to emails that were part of the Paradise Papers leak.

Three months after the storm had made landfall, on Dec. 19, the hurricane center declared Odile’s landfall pressure 941 millibars — 9 millibars too high to trigger a payout. The hurricane center said its number came from Morgerman.

“An observation of 943.1 millibars … was measured by a storm chaser at the Holiday Inn Express at Cabo San Lucas, Baja California Sur,” the authors of the report wrote. “Based on this observation, which is judged to be very near Odile’s center at landfall, the estimated landfall pressure is 941 millibars.”

Mexico received nothing.

“I was completely surprised,” said Perez, the former Finance Ministry official. His understanding was that “if the trigger occurred, OK, [we’d get] an automatic payment.”

Nearly the same situation played out the next year when Hurricane Patricia passed near Emiliano Zapata, a small town near Mexico’s southwestern coast where, again, Morgerman was holed up in a hotel. Using Morgerman’s readings and those from local stations, the hurricane center revised its initial pressure estimates up again, downgrading the anticipated payout from $100 million to $50 million.

Morgerman works independently and said he had never heard of cat bonds before Hurricane Odile. He said since 2014 he has been paid enough by various media outlets, including the Weather Channel and Discovery, to fund his trips. Before that, he said, he was self-funded.

“I’m aware of the conflict issues,” he said. “There can’t be even an appearance of impropriety in this.… I don’t do this to become rich.”

Nevertheless, the results of his storm chasing have shaken the industry.

Robert Muir-Wood, chief research scientist at RMS, a risk modeling firm that works with issuers and investors to create the data upon which bonds are based, expressed concern that chasers such as Morgerman could influence bond payouts. He’s also worried that others might be encouraged to join him. “In which case, are some of them going to be employed by investor organizations?”

Though the National Hurricane Center has no official vetting process for independent data suppliers, both Franklin, the former director, and a hurricane center spokesman said they were confident errant data would be detected and removed. And they said they trusted Morgerman’s readings.

But Franklin acknowledged that with smaller inconsistencies — a few millibars up or down — “somebody who had malicious intent could probably shave something, and we probably wouldn’t know.”

Karen Clark, the founder of the risk modeling firm AIR Worldwide, said complications over third-party data could become a bigger issue, with more companies claiming to measure data “better than the hurricane center.”

“They see it as a large potential market for a lot of this weather data,” she said of the new entrants. “So the confusion around what actually happens is likely to become compounded.”

Measuring storms is difficult along Mexico’s coasts, where the infrastructure to gather basic information about wind speed and atmospheric pressure is limited.

Under the terms of the bonds, Mexico only receives money when a large hurricane or earthquake of a certain size strikes within a precisely drawn geographic boundary. This type of bond uses what is called a “parametric” trigger, which differs from more traditional bonds that base payouts on financial costs or damages.

One of the advantages of the parametric models, experts say, is they are easy to manage and understand: The bonds either trigger a payout or they don’t.

Mexico’s 2012 cat bond, for example, was designed to pay out if a hurricane with a central pressure of 920 millibars or below neared or struck parts of the Yucatan Peninsula or the country’s northeast coast, according to Artemis, a website that covers cat bonds. For most of Mexico’s Pacific coast, storms with pressures at or below 920 millibars generated a full payment, while those with pressures between 920 and 932 millibars triggered a 50% bond payout.

But the model ultimately depends on reliable and sufficient data.

The National Hurricane Center depends on a variety of data sources. Planes are the most accurate because they trace the exact path of a storm, said Franklin, the former center official.

However, the center doesn’t send planes to monitor every storm that hits Mexico, he added, and for the ones it does, aircraft are sent far offshore, to gather early warning estimates of a storm’s intensity.

That leaves scant data at landfall. The country’s National Meteorological Service has built a network of weather stations along Mexico’s coasts, but it is far from comprehensive.

Between 2006 and 2016, the National Hurricane Center cited, on average, about five central pressure readings per hurricane that made landfall in Mexico, according to an analysis of cyclone reports. During the same period, the hurricane center had an average of 124 central pressure readings for each storm making landfall in the U.S.

The dearth of data from official Mexican sources has raised concern in the industry that investors could pay storm watchers to submit information to influence hurricane center reports, taking advantage of the loophole.

A Finance Ministry spokesman expressed confidence in the hurricane center, saying in a statement it has “autonomy to select the best ways of estimating and forecasting” storms.

Even if ample data had been at the ready, it is unclear whether the bonds would have provided a quick payout.

Speed is a key selling point for parametric triggers. Unlike more traditional catastrophe bonds, which are triggered by a financial tallying of a disaster, parametric bonds are paid out based on observable, on-the-scene data points, such as earthquake magnitude or a hurricane’s central pressure reading at landfall.

In a report written by officials with the World Bank and the government of Mexico, the authors touted the Mexican cat bonds as a means to “provide cover against the risk of not having enough emergency funds quickly after a major disaster happens.”

However, because the hurricane center uses so many disparate forms of information to compile its reports, it often takes months before the agency releases its final verdict.

Between 2001 and 2016 it took an average of 103 days to release a report after a hurricane had made landfall. In the case of Odile, it took 92 days and with Patricia, 100.

“For some purposes of these cat bonds, specifically for emergency relief, it’s too long,” said Dario Luna, a former Mexican Finance Ministry official who supports their use.

The hurricane center said it issues reports “in as timely a manner as possible, given its available staffing and other responsibilities.”

When the bond does pay out, it is difficult to track precisely how the money is spent.

The federal government accounts for its disaster spending in broad terms, without specifying which payments come from which accounts.

A Finance Ministry spokesman declined to say where the $50-million bond payout from Patricia ended up, but said the country followed federal regulations in distributing it.

“My opinion is that obviously we should be insured, but the problem is how you spend the insurance resources that you get,” said Naxhelli Ruiz, a professor in Mexico City who studies disasters.

On Sept. 7, 2017, an 8.2-magnitude earthquake shook southern Mexico, killing at least 98 people and causing extensive damage in the region.

The earthquake was one of the strongest ever recorded in Mexico. The country had finalized a $360-million bond deal just weeks earlier. The payout to Mexico: $150 million.

With that event and the payout from Patricia, Mexico has received $200 million in bond payments, but it has paid about $222 million in premiums and fees since 2006. The government could lose an additional $44 million if no other catastrophes trigger the bonds over the next two years.

As part of a risk management strategy that incorporates reinsurance and government disaster funds, the bonds have proved effective, a spokesman for the Finance Ministry said in a statement.

Other nations are more circumspect.

Many developing countries have concluded the costs are simply too high, especially given the “immensely complex challenge of calculating a once-in-a-century event,” as Eduardo Cavallo, an economist at the Inter-American Development Bank, wrote in a blog post last year.

Some within Mexico’s own government question their design.

Officials in the Auditoria Superior de la Federacion, a public agency, said in a report the catastrophes the bonds had covered “have not been consistent with the events of natural disasters that have occurred in recent years in the country.”

In 2013, for example, Mexico was slammed by back-to-back storms. Hurricane Manuel hit the state of Michoacan, generating dangerous mudslides that buried homes and floods that swamped roadways. More than 100 people were killed. The following day, Hurricane Ingrid hit the country’s northeast, killing more than 30 people.

Together, the storms caused $6.6 billion in losses. Yet neither Manuel nor Ingrid triggered the cat bond because their central pressures were too high. (A Finance Ministry spokesman said other insurance policies provided partial coverage after both.)

When Hurricane Odile struck a year later, it caused more than $1 billion in damage. Again, there was no bond payment because, in that case, the central pressure reading, recorded by Morgerman, was too high.

Morgerman was as surprised as anyone that Odile didn’t trigger a cat bond payout. “It minimizes what was actually a catastrophic event,” he said.

Susanne Rust, Michael Phillis and Asaf Shalev from Columbia University, and Isabella Cota Schwarz from Quinto Elemento Lab, contributed to this report.

Funding for the reporting on this story was provided by the Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Fund, Energy Foundation, Lorana Sullivan Foundation, Open Society Foundations, Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Rockefeller Family Fund, Tellus Mater Foundation and the Tortuga Foundation, as well as by the Investigative Reporting Resource at the Columbia Journalism School.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.