An Iraqi band of brothers: They watch ‘American Sniper’ and play ‘Call of Duty’ – and they’re out to recapture Mosul

- Share via

Reporting from Bartella, Iraq — Just before sunset on the first day of the Mosul offensive, Lt. Col. Ali Hussein Fadil called his soldiers to attention in a field about 30 miles east of the city where they had bivouacked.

After five months of training, and now three days of waiting, the 166-strong Najaf battalion of the Iraqi Special Forces known as Golden Division was itching to deploy. You have, he told them, exactly an hour and a half.

“Get ready and we will move toward Mosul,” Hussein said, his voice stern.

The troops paid close attention to their cleanshaven commander’s instructions, delivered in clipped Arabic: Don’t enter houses alone. Take your bazookas and RPGs. Target suicide bombers’ cars quickly before they reach us. Safety first. Commanders, be responsible for your soldiers. Beware of booby-traps and mines.

Some Iraqi commanders don’t emphasize worst-case scenarios, worried about scaring their troops. Hussein said he wanted his men to be prepared for the worst.

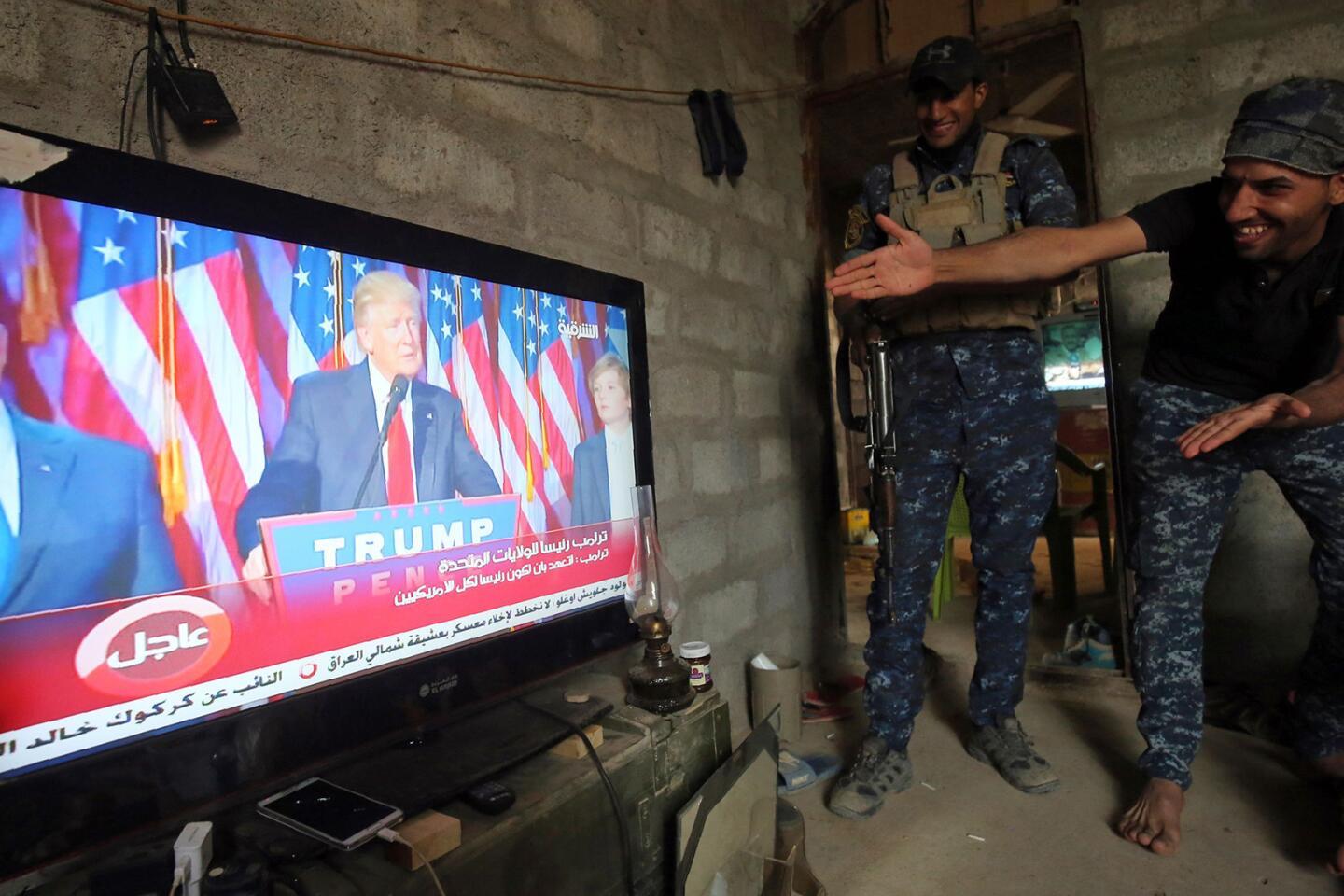

They are modern Iraqi warriors, their training shaped by the U.S. invasion in 2003 and the vigorous fighting alongside American troops that followed it.

Hussein’s favorite movie is “Black Hawk Down.” His soldiers have seen “American Sniper” and “The Expendables,” some several times. Their Humvees are stenciled with the skull symbol of the American comic book hero “The Punisher,” adopted as an emblem by “American Sniper” Chris Kyle. They play “Call of Duty” and post selfies in uniform flashing peace signs. For meals, they must often deal with MREs, the standard field rations of the U.S. military.

Many of his soldiers wear battlefield apparel manufactured by Southern California-based 5.11 Tactical. They carry American M-4 carbines.

“Our supplies, training and equipment are American,” Hussein said, but, “I’m an Iraqi soldier.”

Around his neck, like some of his soldiers, he wears a religious icon, an amulet etched with a Koranic verse about combating evil. His troops have decorated their Humvees with pictures of lions, and nicknamed themselves “The Lions of God on Earth.”

They are Muslims and Christians, Sunnis and Shiites, Arabs and Kurds.

Asked what sect he belongs to, Hussein just smiled.

“I’m working for my country,” he said, “Only my country.”

Raised in Baghdad, Hussein, 36, joined the army in 1998. He has lost more than 50 fellow soldiers in battle since. He himself has been wounded several times, the worst a gunshot wound in his right leg from an AK-47 while fighting insurgents to the south in Diyala in 2008.

Now they were preparing to go into battle again, and said a quick prayer.

“Praise Mohammed, peace be upon him, is your morale high?” Hussein shouted.

Yes, his men replied.

In the first town in their path, the Christian hamlet of Bartella, they could expect to find at least 30 Islamic State fighters, he said, likely lurking in abandoned homes.

“Don’t go too fast or get excited,” Hussein warned. “You have to preserve yourselves. You are heroes.”

::

Mahmoud Mohammed, 26, a Sunni Muslim soldier wearing American tactical sunglasses, had family in a nearby village waiting to be freed from Islamic State.

“They are going to be welcoming us,” he said before they deployed.

Harth Mahmoud, 22, from western Anbar province, hoped to continue the momentum of campaigns that routed Islamic State there from Falluja and Ramadi.

“Tomorrow, God willing, we will drink tea in Mosul,” he said with a grin.

The crowd around him laughed. They knew it would never be that easy. They grew up in a country at war. Many worked with U.S. contractors and soldiers before they trained with them. They wear T-shirts saying “U.S. Navy” and “Glock Perfection.”

A few paused to grab rugs and bow in the dusty field for evening prayer. They came from all corners of the country for this fight: Baghdad and Kirkuk, Anbar and Basra. Soon after, as the sun sank beneath the Nineveh plains, they left to free Bartella.

“We’re like one man,” Hussein said later in Arabic, adding in English, “One team.”

::

“Quickly, send mortars!”

Five days after the Mosul offensive began on Oct. 17, Hussein was in the thick of battle south of Bartella, barking orders into two radios from an abandoned house strewn with debris.

“They are attacking us!” soldiers yelled back over one radio from the front lines a few hundred yards away.

“We need coalition targeting. We need quick reaction,” Hussein called into the second radio, requesting air support from the U.S.-led coalition.

Hussein had propped himself against an overturned loveseat, helmetless, spare ammo strapped to his chest. One radio was clipped to his uniform above his velcro name tag that said “Ali,” the other was in his left hand. In his right, he held his rifle.

Mortars could be heard exploding outside, where spent casings blanketed portions of the path to his command post. The commander did not flinch. Neither did the half dozen soldiers standing guard beside him. He figured the mortars were still a third of a mile away.

Several empty ammunition boxes lay discarded outside. His men had piled full boxes inside the makeshift command post, a one-room peach cinderblock house with broken windows and a length of plastic ivy still dangling from the starburst tile walls.

“There are about 10 car bombers from Hamadaniya coming at us,” Hussein warned his soldiers over the radio, calm. “In a minute, the American drones will deal with that.”

And then, into the other radio: “You have a sniper. I need you to deal with that.”

“They are attacking our sector!” a soldier shouted over the radio as gunfire sounded in the background.

The sniper was advancing, maybe 300 yards away, Hussein said. The house shook as mortars drew closer.

“They are coming toward us,” Hussein growled over the radio, “So deal with that.

More booms sounded on the other end.

“Mahmoud,” Hussein called, “Do you hear me?”

After a pause, Mahmoud responded with more bad news: “They are targeting us with rockets.”

They had captured two villages before about a dozen Islamic State fighters dug in, sheltering in a network of tunnels beneath scores of cinder block homes. Now, they were in a standoff.

They are modern Muslim warriors but they favor “Black Hawk Down” and their Humvees are inscribed with American comic heroes.

So far, Hussein’s men had survived five car bombs, shooting the cars before they got close enough to do damage. They snapped photos of the dead fighters, wearing long beards, skull caps and camouflage, some with suicide vests.

A soldier arrived to report an injury, this time from a mortar. So far, 13 of Hussein’s soldiers had been wounded, including a lieutenant and a captain. One died: Nafel Atia, 34, a father of four from the southern city of Kut, killed by a mortar strike.

The soldier’s family called and prayed for the special forces as they advanced, Hussein said. He apologized that his men would be unable to attend the funeral, saying, “It’s our duty to be on the front lines.”

Hussein suspected that as they drew closer to Mosul, Islamic State fighters would start using human shields. He had heard reports that the militants were forcing civilians out of surrounding villages and into the city, executing some.

At Hussein’s side, Assistant Capt. Rahad Qasim Kareem, 28, said he heard that his family’s home was among those shot up during an attack by Islamic State militants the day before to the southeast in Kirkuk.

That showed the offensive was working, he said. Iraqi soldiers have been criticized in the past for lacking resolve, fleeing in the face of Islamic State’s offensive on Mosul in summer 2014.

“We’re going to change the way Iraqi soldiers are seen,” said Kareem, a thin figure with a special forces cap, neat moustache and tactical sunglasses.

That afternoon, one of their Humvees was hit by a rocket and burned. No one was injured. But some soldiers were shaken.

Hours later, they rolled out with Hussein’s convoy to Bartella for a meeting with commanders. They passed the charred remains of several car bombs and eerie, empty streets. Mortars boomed on the periphery.

::

Waleed Abdel Nabi, 28, a slender, cleanshaven father of four from the southern city of Nasiriyah, is no stranger to explosions. He remembers the 2003 U.S. invasion and the suicide bombings that followed, killing several of his buddies, Sunni and Shiite.

That’s what motivated him to join up. He has since been wounded during recent offensives to drive Islamic State from western Iraq.

His cousin Adl Halaf, 35, shorter with a thick moustache, joined too. Now they share a Humvee stocked with Tiger energy drinks and sunflower seeds, listening to Shakira and debating whether she’s American.

Halaf’s cellphone wallpaper is a photo of his 23-year-old cousin, a police officer in western Rutbah shot by Islamic State.

“After they killed him, they burned the body,” he said.

Nabi knew the soldier in their battalion who died, called his wife to tell her the news and heard her collapse. He still carries his late comrade’s phone.

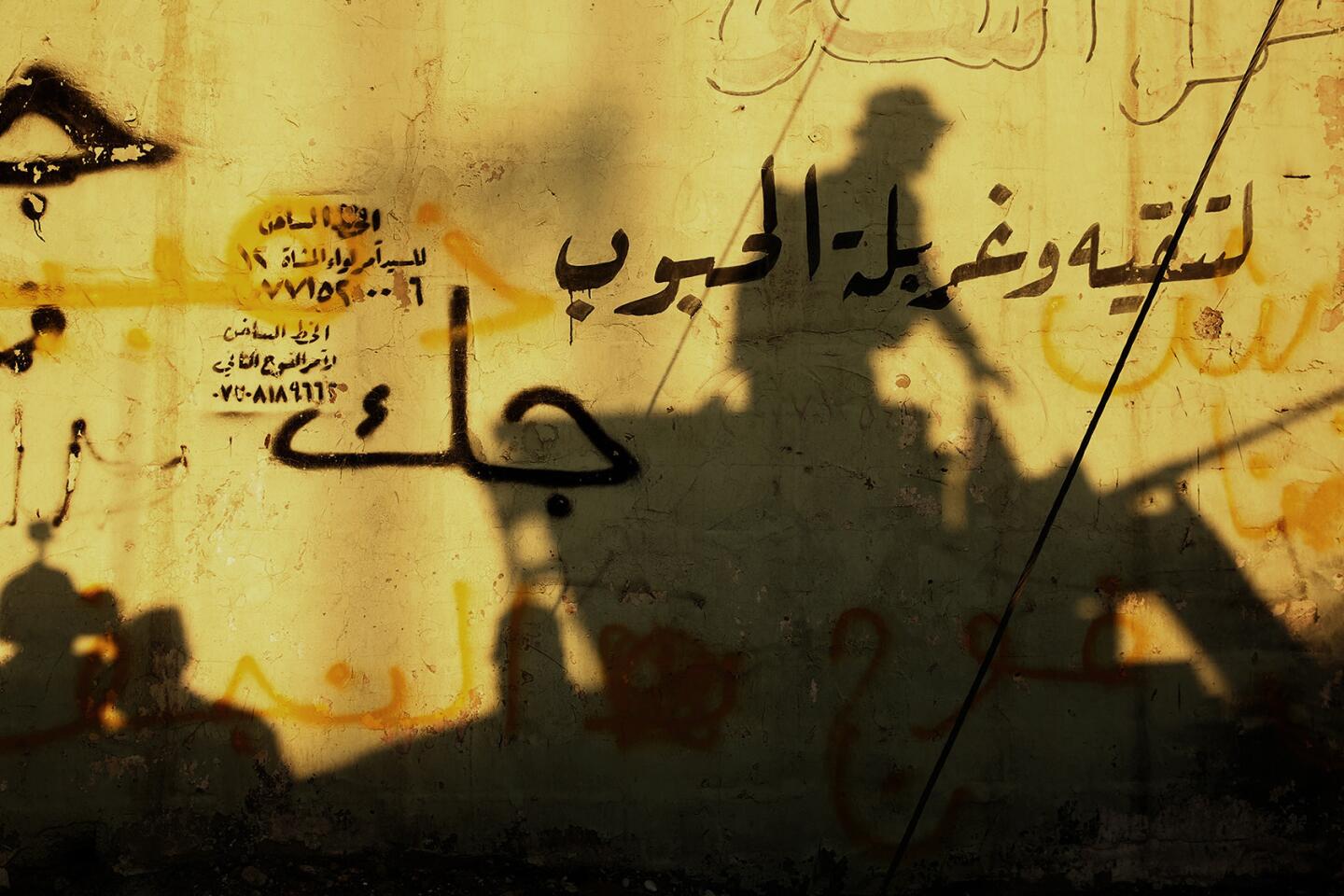

With the convoy parked on a side street in Bartella awaiting their commander, Nabi scanned their surroundings. The town, like all they had freed so far, had been empty for two years. No civilians welcomed them. Instead, they were greeted by pastel houses pocked with bullet holes, each gaping door and shattered window a potential redoubt for snipers.

“Today there was not any progress,” Nabi said, sounding tired.

He could feel a fierce fight coming. Last summer, when they freed the oil town of Qayyarah to the south from militants, Hussein’s men mortared a house where snipers were shooting from the roof, only to later discover a family had been hiding inside.

The family was unharmed, but Nabi never forgot.

Now he sensed the enemy drawing near. Under his black special forces cap, his dark eyes darted from side to side. He turned up his radio, leaning in the door. Was that Islamic State chatter?

Fellow soldiers gathered around Nabi’s Humvee to listen. What they heard did not bode well.

“They are asking for reinforcements,” he said.

::

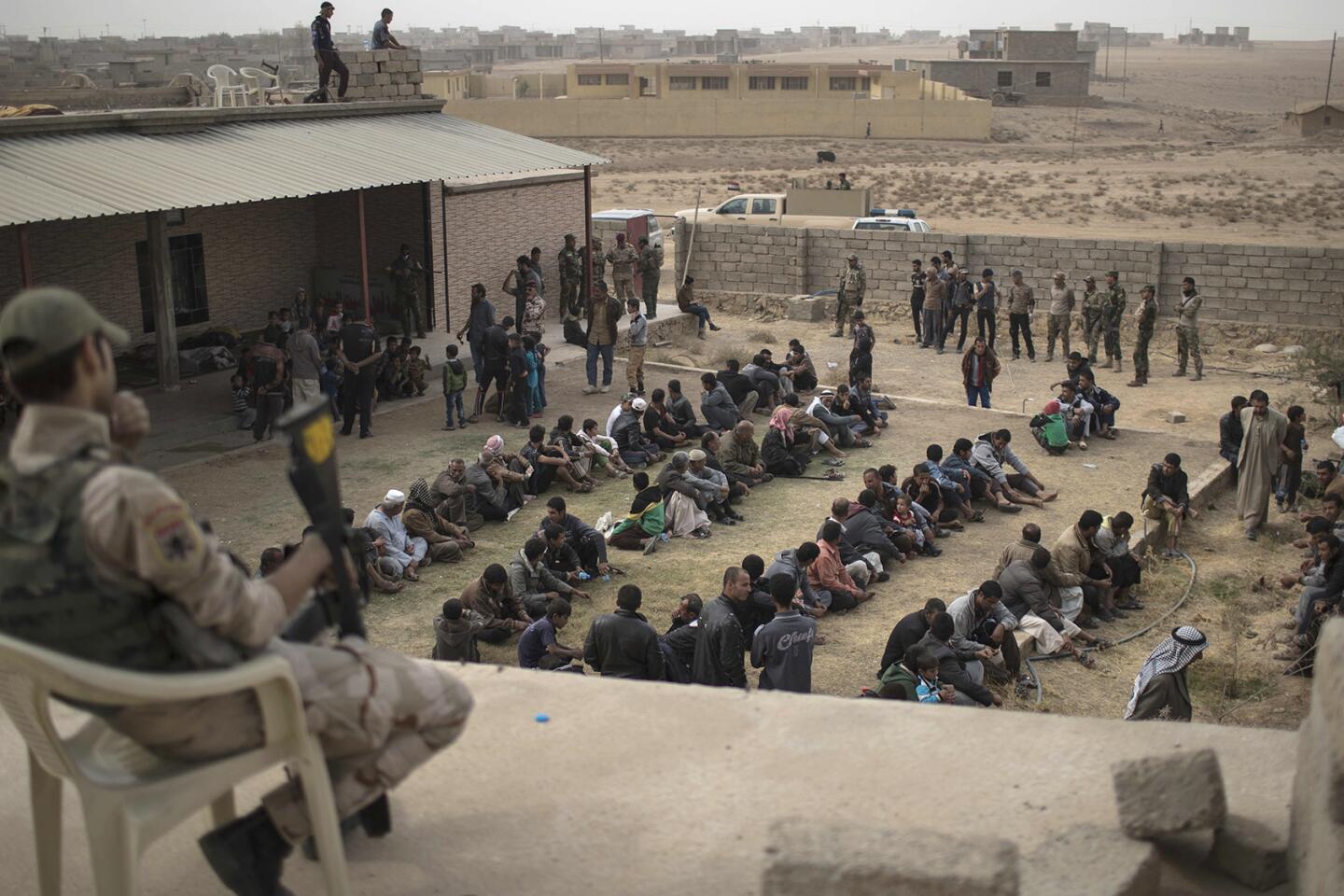

At a military checkpoint outside Bartella on Tuesday, families of those held captive by Islamic State pinned their hopes on the Golden Division.

Several miles west, about 40 militants were sending a half dozen suicide bombers toward Hussein’s soldiers, sniping at them while darting between tunnels.

Car bombs destroyed two Humvees. But by day’s end, Hussein’s forces had killed nine militants and forced the rest to flee. The soldiers suffered no injuries or casualties. They seized Islamic State ammunition, an antiaircraft gun and radios they hoped to use to spy. And they captured two villages.

Both were empty.

“Islamic State took most of the civilians here back to Mosul,” Hussein said from his command post the next day, next to some relics salvaged from the villages, including an Arabic-language Bible.

But he said securing the area allowed hundreds of civilians farther west to flee the village of Tob Zawa. They greeted soldiers with white flags signaling their support, jubilant. They cut their beards, borrowed soldiers’ phones to call relatives they had not spoken to in years, and praised the offensive.

“We were waiting for the army to come and save us,” said Wali Sadala, 73, a farmer who drove out on his tractor with his extended family in tow.

“They did a good job, especially Golden Division. They had a good plan to rescue people,” said Saber Jergis, 35.

Civilians from other nearby villages returning later to check their homes thanked Hussein’s troops.

In the village of Sheikh Amir, the soldiers were sweeping for mines when they stumbled upon a set of gold wedding jewelry. Then they found the elderly owner, still in shock after finding his home destroyed.

When he saw the gold, Hussein said, “It was as if he came back to life.”

One of Hussein’s men, Saud Messoud Jamal, 31, is from Sheikh Amir, which his family fled two years ago. He found their home mortared, loaded with mines and robbed; even their 30 sheep were gone. Militants had scrawled graffiti on the walls, including: “God’s messengers.”

“They knew that I was working with Golden Division,” said Jamal.

But recapturing the town, even in ruins, felt like getting his homeland back.

Now he and the rest of Hussein’s men must go house to house, checking to ensure militants don’t re-infiltrate.

Before climbing a hill near his command post to survey the area with his men on Friday, Hussein snatched the starred officer’s epaulets from his shoulders, smiling ruefully.

“Snipers,” he said in English – they know to target officers.

This hill was once a cemetery, with one grave left. As he passed it, Hussein slung an arm over Nabi’s shoulder. The fate of these soldiers weighs heavily on the commander, who is having trouble sleeping. His men hear him on their radios at all hours, checking in.

Hussein doesn’t like calm days like this, so quiet he can hear the wind kicking up dust. Militants attack during dust storms, he said, making use of the cover. And they want this area, a strategic post along the highway to Mosul.

At the top of the hill, Hussein pointed to a radio tower at the edge of Mosul. There was smoke on the horizon, fires set less than a mile away by Islamic State.

The night before, a dozen militants, some of them suicide bombers, had climbed the hill to attack. Hussein’s soldiers were ready to repel them, patrolling with night vision goggles.

They held the line, for now.

molly.hennessy-fiske@latimes.com

ALSO

Even the badly wounded are itching to return to the battle for Mosul

Facing Iraq government-led Mosul offensive, Islamic State extremists strike back

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.