Garcetti wants better earthquake safety for L.A.’s day care centers, private schools and steel towers

- Share via

Mayor Eric Garcetti on Friday called for Los Angeles to significantly improve its planning for a major earthquake, saying the city should consider mandatory retrofits of steel-framed buildings and earthquake evaluations of private schools and day care centers.

Los Angeles already has some of California’s strongest quake retrofit laws, which cover brick buildings, concrete-frame structures and wood-frame apartments. Friday’s announcement marks the first time Garcetti has specifically raised the possibility about whether the city should require the retrofitting of vulnerable steel buildings built before the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

Government experts have said that, during a major earthquake, it is plausible that five steel-framed buildings across Southern California could collapse.

We can’t wait for catastrophes to hit before confronting them.

— Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti

More than 400 people could die and more than 800 could be injured if those five buildings collapsed, a U.S. Geological Survey study has said. Santa Monica and West Hollywood recently passed laws requiring vulnerable steel buildings in their cities be retrofitted.

“There are buildings in Los Angeles that have slipped through the cracks. But we can’t let people in an earthquake be killed by those cracks,” Garcetti said in an interview. “Sometimes it takes political courage, but we have to make sure we don’t look back after an earthquake and have lives that were lost and say, ‘Well, we did as much as we could.’ ”

Added the mayor: “I just believe we can do more. We found where we can do more. And so it’s not a question of if — now we have to tackle how.”

Garcetti said the time has come to establish a plan to broaden not only the city’s efforts on earthquake safety, but on other menaces faced by America’s second-largest city, such as wildfires and worsening extreme heat.

“We can’t wait for catastrophes to hit before confronting them,” the mayor said in a statement.

96 goals for a ‘Resilient Los Angeles’

Some of the recommendations in the “Resilient Los Angeles” report are new; some have been discussed before, such as goals to build 100,000 new residential units by 2021 and building new housing for the homeless, while others have more specific details. Among the key recommendations:

- Develop customized disaster preparedness plans tailored to all of Los Angeles’ neighborhood councils. A specific plan for Venice might focus on sea-level rise; Chatsworth, wildfire danger; and the Hollywood Hills, mudslides.

- Create disaster preparedness and response centers in Los Angeles in the city’s most vulnerable neighborhoods by 2028. So-called Neighborhood Resilience Hubs would be located in buildings such as a city recreation center or a community organization’s offices. After an earthquake, such places might be able to keep the lights on even during a widespread power outage, allowing residents to recharge cellphones; help keep them informed through satellite communications; and offer extra supplies of food and water.

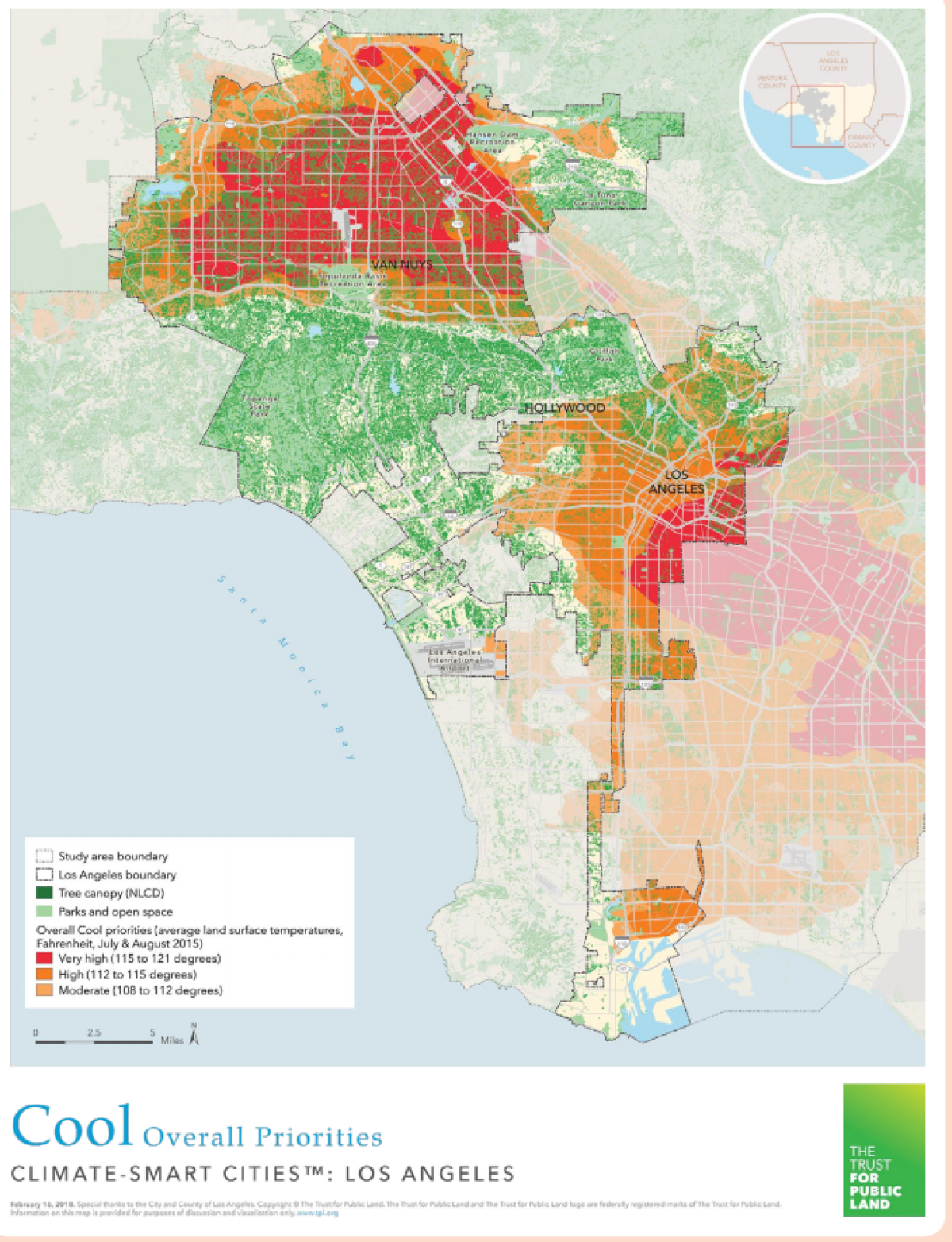

- Launch projects to cool neighborhoods as Los Angeles faces a future with more days of extreme heat, such as planting more trees and painting streets whiter to reflect heat back into the air. Areas that can become particularly warm, where summer average land-surface temperatures can exceed 115 degrees, include Boyle Heights, El Sereno and much of the San Fernando Valley.

Areas in red show where average land surface temperatures rose to between 115 and 121 degrees in July and August 2015 -- areas that are priorities for cooling down. Orange areas had temperatures of 112 to 115 degrees, and yellow areas, temperatures between 108 and 112.

- Develop and eventually adopt stronger minimum earthquake building standards for new structures. Currently, new buildings must be built only to a level to prevent killing people during an earthquake, but they are allowed to be so damaged that they will need to be torn down.

- Expand the mayor’s Office of Resilience and have city departments pick their own resilience officers to get these goals accomplished.

One key aspect includes trying to get neighbors to get to know each other and prepare to help each other when a disaster strikes; 1 in 3 Americans say they’ve never interacted with their next-door neighbor.

Garcetti wants more Angelenos to join the Community Emergency Response Team, or CERT, in which groups of residents receive nearly 18 hours of training in areas such as searching for and rescuing victims, extinguishing small fires and providing basic medical aid.

A focus on neighborhoods

During the Northridge earthquake, neighbors ended up being rescuers, as firefighters were overwhelmed with the scale of the disaster in the first hours.

“We can only overcome our greatest threats if we work together,” Garcetti said.

The Resilient Los Angeles report comes more than two years after the city received its first chief resilience officer, Marissa Aho. Her position initially was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities program, which aims to get cities not only to prepare against earthquakes, fires and floods, but against other threats that endanger the fabric of society.

MORE: The hidden earthquake danger lurking in single-family homes »

“If left unaddressed, any one of these stresses will not only continue to negatively impact Angelenos’ daily lives, but also exacerbate disasters when they occur,” Aho said in a statement.

The Rockefeller Foundation has spent $164 million to change the way cities plan and act around their risks. “Cities rarely have a good idea of what they’re going to face next. What resilience tries to do is help cities think about building strength in a more holistic way,” said Michael Berkowitz, president of the 100 Resilient Cities initiative.

Protecting cities from more than earthquakes and floods

For example, the catastrophe that struck New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina wasn’t caused only by the warmth of the Gulf of Mexico combined with the ferocity of the storm and the vulnerability of the levees, but also by impoverished neighborhoods, endemic racism, a lack of mobility and the lack of trust in institutions, Berkowitz said.

One of the 100 Resilient Cities is Paris, whose challenges include climate change and accommodating an influx of refugees. Paris is launching a pilot project to reconstruct interior concrete courtyards in the city’s schools and transform them into green spaces.

Not only would that reduce urban heat and help store rain in groundwater basins, but the green spaces also can be opened to the public to help integrate the city’s newest residents into French society, Berkowitz said.

But there can be challenges in executing resilient solutions. For instance, an effort to combine twin goals of protecting a city from floods while also increasing and connecting park space can sputter.

Coming up with a list of goals like those from L.A. is a good start, Berkowitz said. Still, “it will take a lot of focus to get it done,” said Berkowitz, former deputy commissioner for the New York City Office of Emergency Management.

How steel buildings can collapse

Earthquake safety takes a prominent role in the 178-page report. It says that the mayor’s Seismic Safety Task Force “will re-evaluate whether to recommend mandatory retrofits ... such as steel buildings constructed before 1994.”

Steel buildings once were considered by seismic experts to be among the safest. But after the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake of 1994, engineers were stunned to find that so-called “steel moment frame” buildings fractured. About 25 were significantly damaged in the Northridge quake.

No steel building suffered a catastrophic failure that killed anyone in that earthquake, but some were so badly damaged they had to be demolished. One — the Automobile Club of Southern California building in Santa Clarita, open for just 21 months — came very close to collapse.

“The flaw exists almost universally of buildings of this type constructed from the early 1970s through 1994,” structural engineer Ronald Hamburger has said.

Among the reasons for the flaws in steel buildings were problems in welding technique and inspections, the filler metal used in the welds and the basic configuration of the connection between vertical columns and horizontal beams.

The same problem was found in 1995 when a magnitude 6.9 earthquake hit Kobe, Japan. One-third of 630 modern steel buildings in a heavily shaken area were severely damaged, according to a USGS report. One photographed building shows how one story of a steel building collapsed.

Earthquake retrofits of private schools and day cares

The report also says the city will develop a mandatory seismic evaluation program that prioritizes buildings with private schools and day care centers.

Government officials have long known that California’s private schools generally are not regulated for earthquake safety; San Francisco in 2014 became the first city in the state to require that private schools assess whether classroom buildings would collapse in an earthquake.

There are more than 350 private schools in Los Angeles, attended by more than 70,000 children.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.