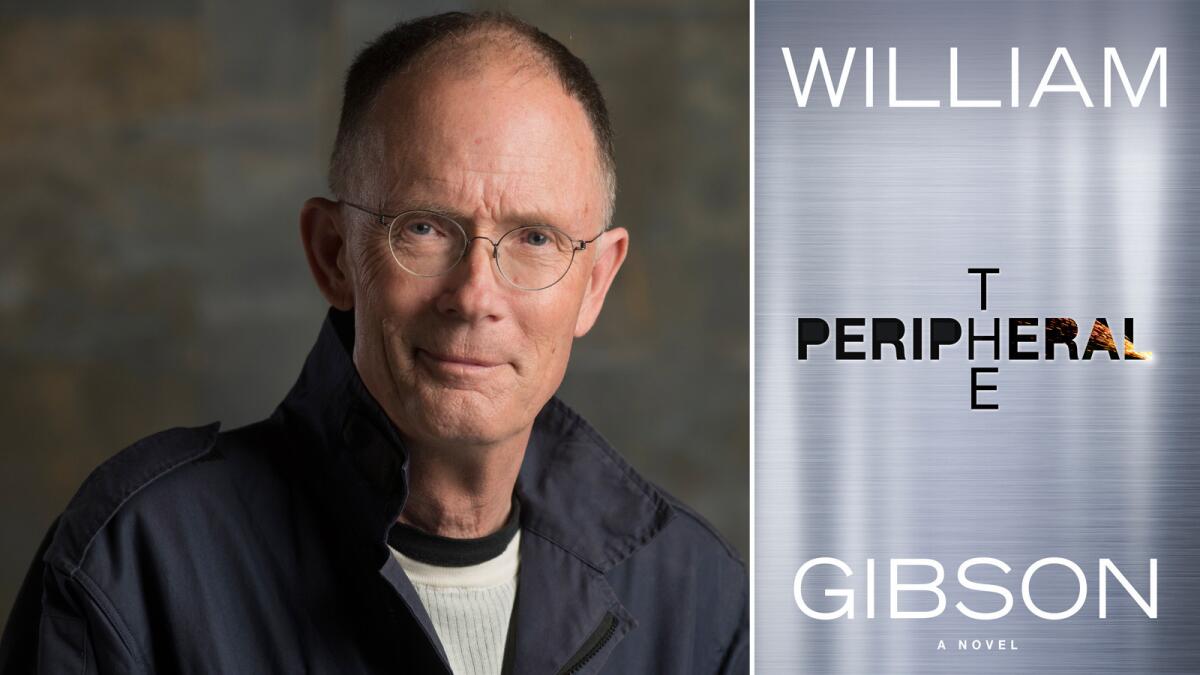

William Gibson coaxes the future out of the present

- Share via

“I wanted buzzwords,” William Gibson says of his early writing ambitions. “I wanted buzz-neologisms, really.” He scored with “cyberspace,” the term he coined in a short story and popularized in his 1984 novel “Neuromancer,” to describe, well — never mind, you know what cyberspace is.

But we didn’t then. In an era when “Dynasty” and “Dallas” dominated the airwaves and people marveled at the first Apple Macintosh computer, the idea that personal computers might connect to a notional space for business and communications that could be broken into, hacked — that was the stuff of fiction.

“It’s fairly common for other people to say that lots of things in ‘Neuromancer’ subsequently came to pass, but I don’t myself say that,” Gibson says with a laugh. He’s talking by phone from his home in Toronto, short, frequent bursts of laughter underscoring an element of absurdity, amusement.

The burden of his prophetic debut novel is that he’s frequently thought of as a futurist, although he dodges when asked about the label. His fiction resists it: In his new novel, “The Peripheral” (Putnam, 496 pp., $28.95), two story lines in different futures intersect via an unexplained, quasi-quantum technology. The science is more fairy tale than futurist, “very hand-wavy and vague,” Gibson says. “That’s a deliberate and I think comic violation of what some people would suppose my job description to be.”

“The Peripheral” is a fast-paced mystery that takes place in two futures, one several decades hence and the other 75 years beyond that. The latter is a much-transformed but recognizable London; the former, a rural American town with little going on but an illegal drug trade, a megastore called Hefty Mart and an indie 3-D print shop. With these worlds mysteriously intersecting, the book’s heroine, Flynn, witnesses a murder, inadvertently putting her small town in danger.

“It became colored with my childhood sense of what a small American town is like, which is a very Southern sense of what a small American town is like,” Gibson says. Raised in South Carolina and Virginia, Gibson’s voice has a soft Southern lilt, interrupted by “agayn” for “again,” “bean” rather than “been.” Gibson drifted to Canada during the Vietnam War and stayed; he’s married and raised his family there.

Gibson is a countercountercultural baby boomer: He went to Woodstock and thought it was a bust, never got Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run” but was transfixed by “Nebraska.” “That was a really powerful influence on my work,” he says of the stripped-down, bleak record. “When I heard that I began to think what it would be like to apply that aesthetic to science fiction.”

The outsider looking in: Gibson savvily applies that to his own relationship with technology. He was late to give up his flip-phone because not having an iPhone allowed him to observe — “dispassionately, anthropologically” — how other people interacted with theirs.

It’s an interesting approach, needing to be close to technologies that promise the future but not too close. He tells a pre-Internet days story of being at the bar at a science fiction convention and hearing two women — former Pentagon key-punch operators — talking about computer viruses, then obscure and mysterious. “I just went home completely full of it. I didn’t really know anything about it — I was decoding it poetically,” he says. “I operate from the vernacular poetry of technology and from watching how people interact with technology.”

Twelve books in, Gibson knows his process. “What I have to do is write a first sentence that’s capable of sucking me through the white wall of the blank first page,” he says. “Once I’m really working, I’m never not working, which is kind of a drag. The process sort of constitutes an altered state, and it can take days to do it, get the altered state up and running. I’ve learned to put everything on hold and just stay there.”

And yet he still gets stuck. Filling the far future of “The Peripheral” with “WTF inventions and hair-raising nanotechnology,” as he puts it, was challenging. That future’s setting, built around a man he calls Character B, didn’t come together until he visited his friend and fellow novelist Nick Harkaway in Hampstead.

“He explained the political workings of the city of London. To this day, I don’t know whether he was completely pulling my leg or whether it was an accurate description,” Gibson says. “But I was, like, wow, that’s the weirdest thing I ever learned about Great Britain. By the time I left him that afternoon, I had decided that Character B was in a version of London where all the things that Nick had described were present but hugely amplified. If that seems absurdly random, it is!”

Anything, everything feeds his imagination. He used to buy magazines in volume, hundreds of dollars at a time. “I needed to optimize novelty aggregation,” he says. “Magazines, as a technology, were built and really intended to aggregate novelty.” He’d flip through them while writing, looking for “hits of novelty” he could re-imagine and incorporate.

Now he’s got Twitter. “Twitter now provides that in an almost lethal purity,” he says. “This thing that used to leak out of a pipette one drop at a time has become a fire hose.”

Like a blue whale gulping tons of water and spitting it out for the krill it needs, some part of Gibson has evolved to be very, very good at filtering information overload for just the right elements for his future fictions — which in the years to come might look like predictions.

Twitter: @paperhaus

------------

William Gibson reading

WHEN: Sat. Nov. 1 at 5:00 p.m.

WHERE: Skylight Books, 1818 N. Vermont Ave., Los Angeles

INFO: www.skylightbooks.com/event

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.