Review: Getting physical yet playing it safe at the Bowl

- Share via

The novelty at the Hollywood Bowl Thursday night was not the dance. Nor was it Diavolo.

Curious as it may seem for so vast a venue, the Bowl once hosted ballet on a regular basis. And in recent years, the Los Angeles Philharmonic has revived the idea of choreography in the Cahuenga Pass, commissioning Diavolo, the acrobatic local dance company, to produce new dances to scores by Esa-Pekka Salonen and John Adams.

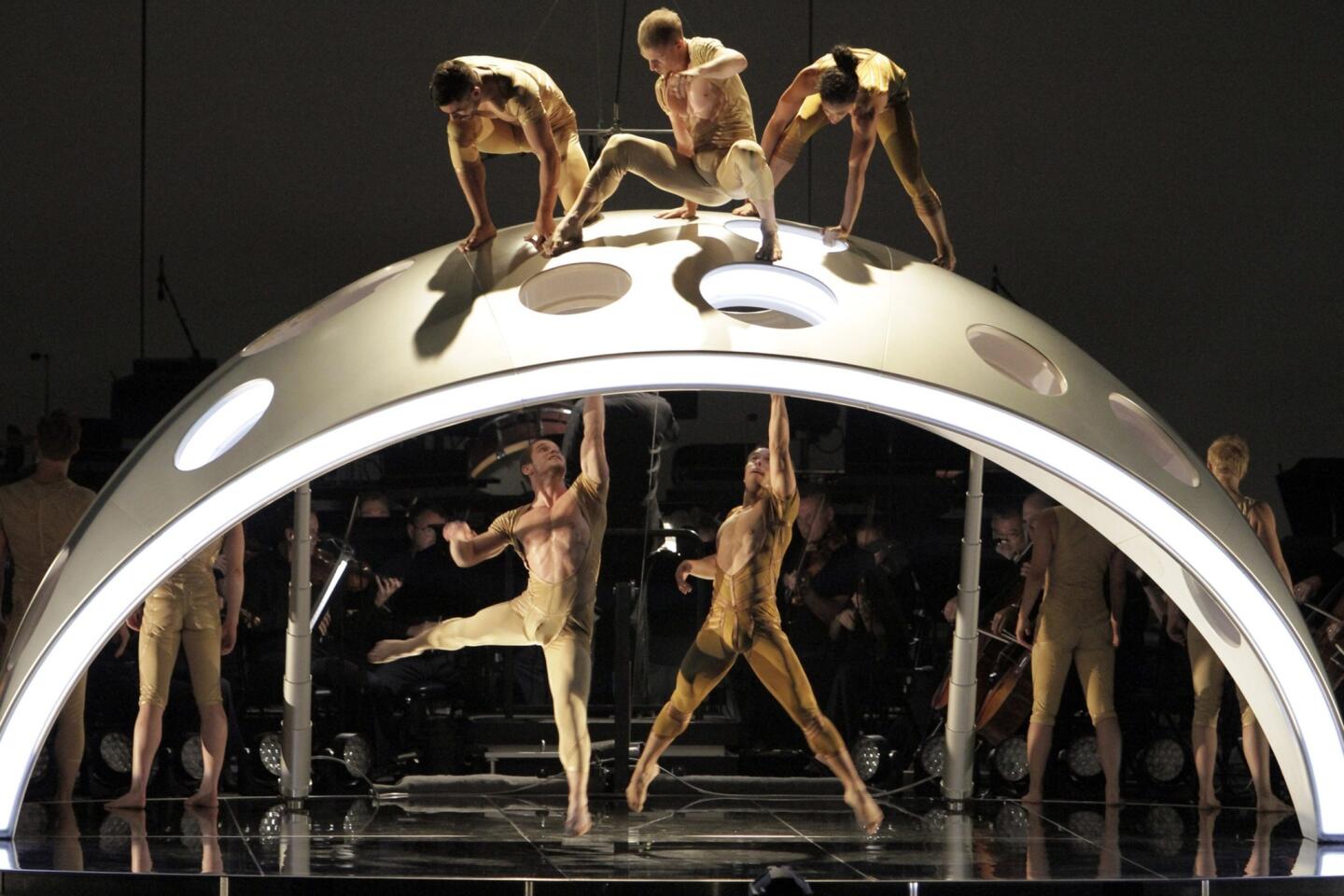

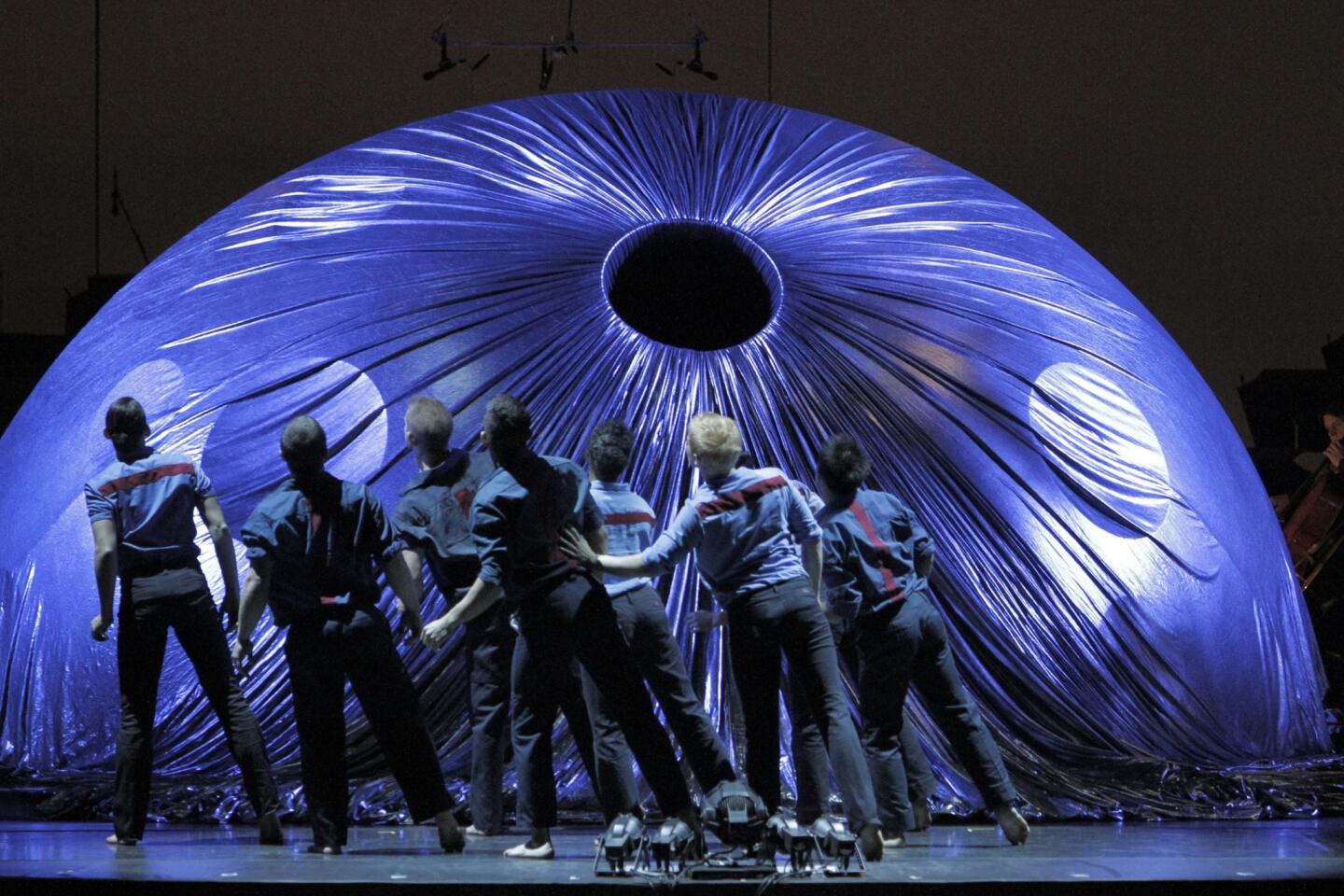

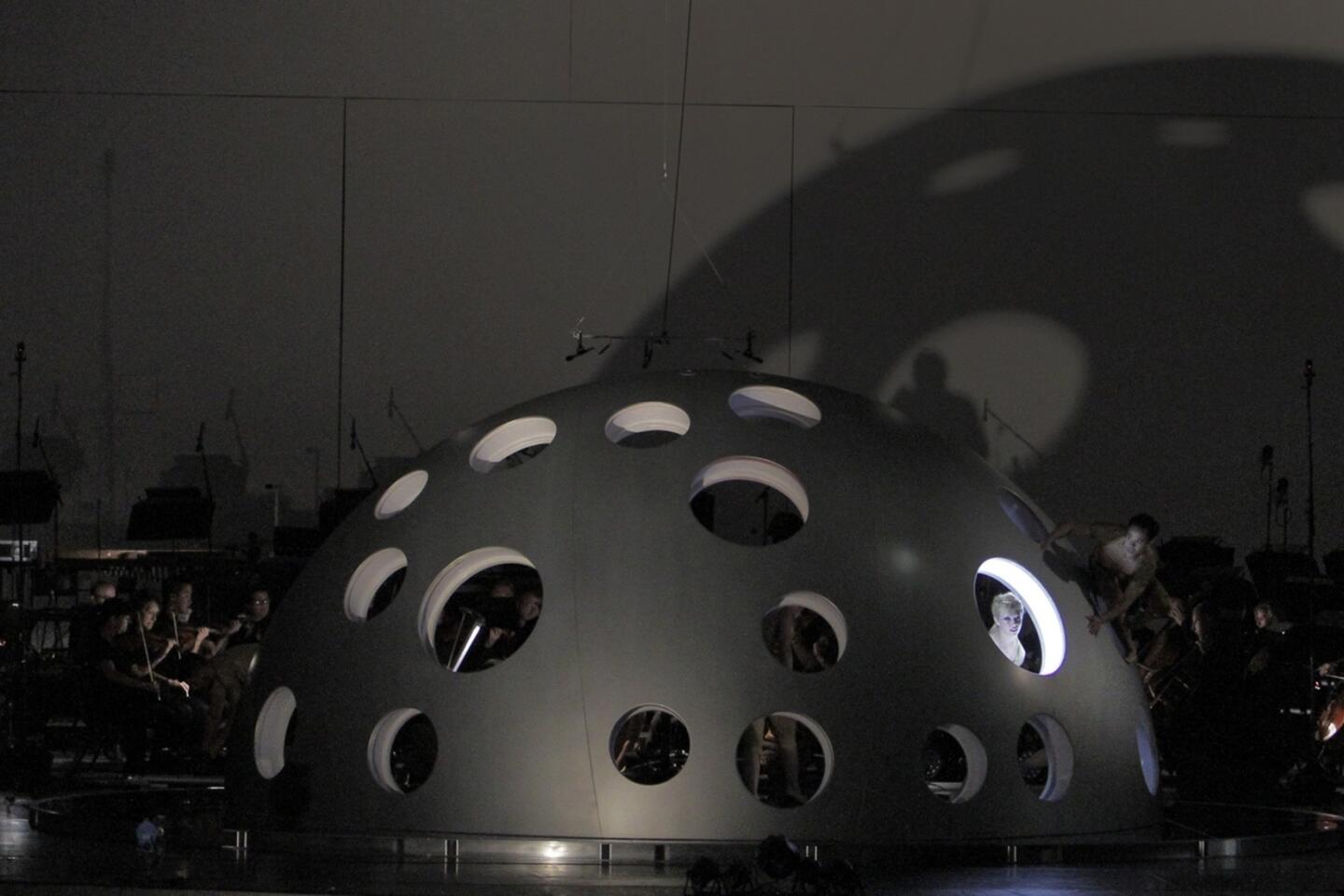

On Thursday, Diavolo’s artistic director Jacques Heim turned to Philip Glass for “Fluid Infinities.” A dozen dancers crawled all over a large dome and popped out of its portholes to the accompaniment of Glass’ Third Symphony, conducted by Bramwell Tovey.

PHOTOS: LA Opera through the years

Glass is no longer a summer L.A. Phil novelty, either. Although it has been only five years since the Bowl’s Glass ceiling was shattered, it has been well shattered, and the composer’s music has been shown to attract good-sized crowds.

Still, there is a lot of Glass to go (fluid infinities nicely describes this prolific composer), and what was new was the programming of a Glass symphony at the Bowl. Perhaps this can be taken as a sign that Glass’ symphonies are slowly beginning to enter the repertory. Few major U.S. orchestras have yet to play one (including the composer’s hometown band, the New York Philharmonic), but the L.A. Phil co-commissioned the Ninth, which the orchestra performed last year in Walt Disney Concert Hall. The latest, the Tenth, had its U.S. premiere at the Cabrillo Festival in Santa Cruz this summer.

The Bowl being the Bowl, though, the L.A. Phil played it somewhat safe. Not only was Diavolo on hand as a crowd-pleaser, but the Third is the runt of Glass’ symphonic litter, written in 1995 as a chamber symphony for just 19 strings and lasting but 24 minutes.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

Why dance to the Third, which is in four classically restrained movements, when Glass has written much buoyant dance music, much of it, such as a story ballet for La Scala (“The Witches of Venice”), never performed in L.A.? Heim didn’t really answer that question, but his company is not alone. “Same Difference,” which Nederlands Dans Theater brings to the Music Center in October, uses the same symphony’s third movement.

“Fluid Infinities” completes Heim’s Bowl trilogy, “L’Espace du Temps” (Space of Time). As with the other two L.A. Phil commissions — to Salonen’s “Foreign Bodies” and Adams’ “Fearful Symmetries” — the French choreographer plays with geometry as much as with movement. Along with the big dome, which flips open, he also has a Plexiglas tube, which a dancer can crawl through and which slightly resembles a discount version of the spaceship cylinders that Robert Wilson created for Glass’ opera “Einstein on the Beach,” also headed to the Music Center in October.

The core of the Third Symphony is the slow third movement, a beautiful chaconne. Each repetition of a chord sequence takes on a new glow with the addition of new players and marvelous new contrapuntal lines. The other movements are rhythmically striking but more conventional Glass.

TIMELINE: Summer’s must see concerts

Diavolo’s Glass is not structural but more akin to Google glass. The dome and tube were vaguely futuristic. The lighting on stage was muted, on the video screens, more like neon. You could choose what to look at; what the cameras selected, which were often close-ups, or what you saw on the stage (assuming you had binoculars if you weren’t close up).

In the boxes, heads bobbed back and forth between stage and screen.

The dancers were, like insects, all over the place, exploring every inch and orifice of the dome, in their own worlds. Fun to watch, they provided spectacle for spectacle’s sake. The orchestra — hidden behind the dome and doubled to 38 strings — gave a muscular, forward-driving and slightly rough-edged account of Glass’ Third under Tovey.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

That pretty much describes the purely orchestral first half of the evening as well. Keeping to the dance theme, Tovey began with Adams’ “Chairman Dances.” Written 10 years before Glass’ symphony and a kind of response to Adams’ “Nixon in China” (which has its own ballet), “Chairman Dances” is a virtuosic imaginary dance (Adams calls it a fox trot for orchestra). Tovey (or was it the sound engineers?) highlighted percussion and piano to create a bizarre swagger that suited Mao just fine.

Tovey also included a half-hour selection from Prokofiev’s ballet “Romeo and Juliet,” which the conductor first introduced at the piano, describing, with cutting wit, the way Prokofiev’s music theatrically informed Shakespeare.

There was next to no sentimentality in Tovey’s performance of the excerpts that centered around the balcony scene and the death of Mercutio. But there was a pointed, ferocious theatricality that transcended everything else, as if Tovey were trying to say that the most dramatic dance is in your head.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.