John Williams’ mastery on display at L.A. Philharmonic season opener

- Share via

You didn’t have to be a fan.

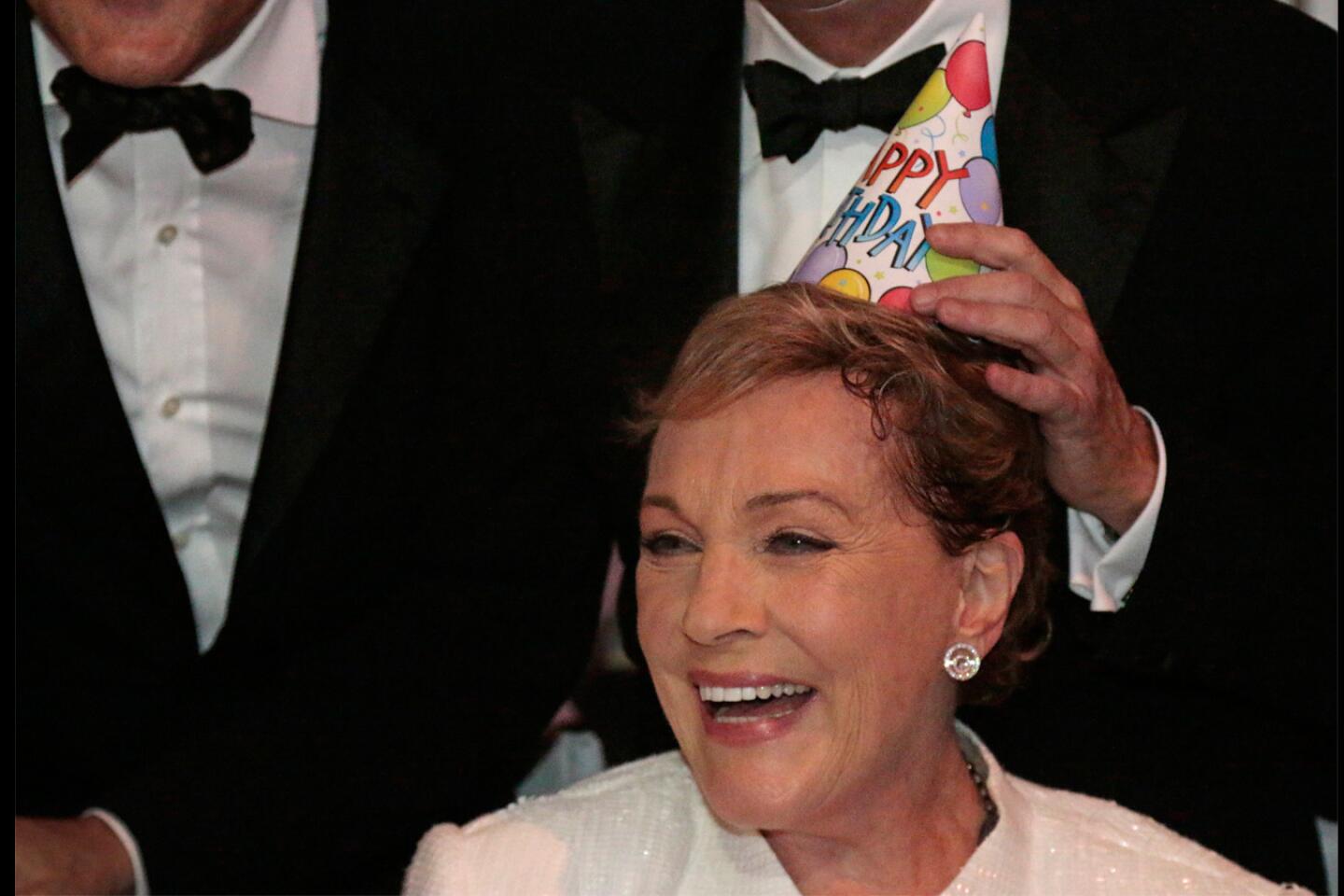

Of course, nearly everyone was Tuesday night at the John Williams celebratory gala at Walt Disney Concert Hall that Gustavo Dudamel led to open his sixth season as Los Angeles Philharmonic music director.

Williams, as everybody knows, is beloved in Hollywood. Studio heads and stars paid thousands of dollars to attend the concert and a fancy dinner afterward, one of the season’s most glamorous cultural social events. “Star Wars,” “Jaws,” “Schindler’s List” and a long list of other blockbusters would have busted far fewer blocks without his enthralling scores. Williams’ 49 Academy Award nominations is a number exceeded only by Walt Disney.

There was, nonetheless, room for skepticism. Two weeks ago the New York Philharmonic was widely criticized for dumbing down Alan Gilbert’s sixth opening night gala with a program of music from Italian cinema, which included great scores performed in easy-listening arrangements and accompanied by trite animation.

Yet even that might have seemed sophisticated compared with a gala that began with the single most populist piece of symphonic music on the planet. The Olympic Fanfare and Theme was surely heard by billions of people this year alone during the broadcasts of the Winter Games from Sochi.

On Tuesday, 14 members of the U.S. Army Herald Trumpets stood on side terraces of Disney to begin the fanfare. A large video screen projected the logo of the Los Angeles 1984 Olympic Games, for which Williams’ fanfare was commissioned. Colored spotlights circled the audience.

“The human spirit soars,” Williams wrote in his program note, describing his feeling of the Olympics. And damned if it didn’t, as these stirring trumpets resonated solemn splendor.

The L.A. Phil, moreover, has proud ownership of this fanfare. The premiere was at the Hollywood Bowl 30 years ago. Tuesday, Dudamel made the orchestra glow with a warmth and majesty that remained throughout the evening.

The L.A. Phil has an even longer relationship with Williams. In the ‘70s, the orchestra built a special program at the Bowl around “Star Wars” that was widely copied around the world for years. Williams is a regular conductor of the L.A. Phil, and many of the players have also recorded film scores with him in the studio. The chimes tune heard in the lobby of Disney announcing the end of intermission was written by Williams.

Even so, Dudamel brings something new to the relationship. He is an unabashed Williams enthusiast who grew up, like all kids of his generation, on “Star Wars” films. When writing his film score for “The Liberator,” the Venezuelan Simón Bolívar biopic that opens this week, Dudamel turned to Williams for advice.

The evening’s program ended with music from “Star Wars” and included excerpts from “Schindler’s List,” played by violinist Itzhak Perlman, who performs on the soundtrack. But it also included other sides of Williams.

Most important was Dudamel’s revival of “Soundings,” the piece Williams wrote for one of the three opening programs of Disney in 2003. It is a kind of soundtrack for a concert hall, telling the story of a venue’s awakening, glistening, responding and rejoicing. A flute plays a motive, an unseen flute offstage responds. Sterling brass, glittering percussion, shimmering strings bounce melodic sparks off the walls. The space, as if it were a character in a coming-of-age film, comes alive.

On this occasion, the hall had help it probably didn’t need from the British video artist Netia Jones. Still, her animated Disney images were lively and fanciful.

Perlman gets credit for not milking the three pieces from “Schindler’s List” or the Paganini-esque Cadenza and Variations from “Fiddler on the Roof,” the concert piece Williams concocted for the film adaptation of the Jerry Bock musical. But that simply may be because Perlman can no longer achieve the beautiful sound he once possessed. He’s lost some charisma too, but Dudamel made up for that with spiritual intensity and, in “Fiddler,” jazzy joy.

Duel music from “The Adventures of Tintin” was used as background for an amusing video montage of swashbuckling movie sword fights throughout the decades. Saxophonist Dan Higgins, vibraphonist Glenn Paulson and bassist Michael Valerio were brought in for jazz-flavored “Escapades” from “Catch Me If You Can.”

To accompany “Throne Room” and the Finale of “Star Wars,” which Dudamel conducted with the magnificence of a space-age Pomp and Circumstance march, Jones animated original storyboard sketches. Music that has become cliché felt renewed, as if Williams’ score were what prodded the creative process.

Williams’ most lasting legacy is likely to be his influence on children. Dudamel is hardly alone. No composer in history has so infused young people with symphonic joy. As an encore surprise, the Los Angeles Children’s Chorus marched down the aisles singing the moving anthem, “Dry Your Tears, Afrika,” from “Amistad,” and then ran offstage screaming as Dudamel mischievously cued up the theme to “Jaws.”

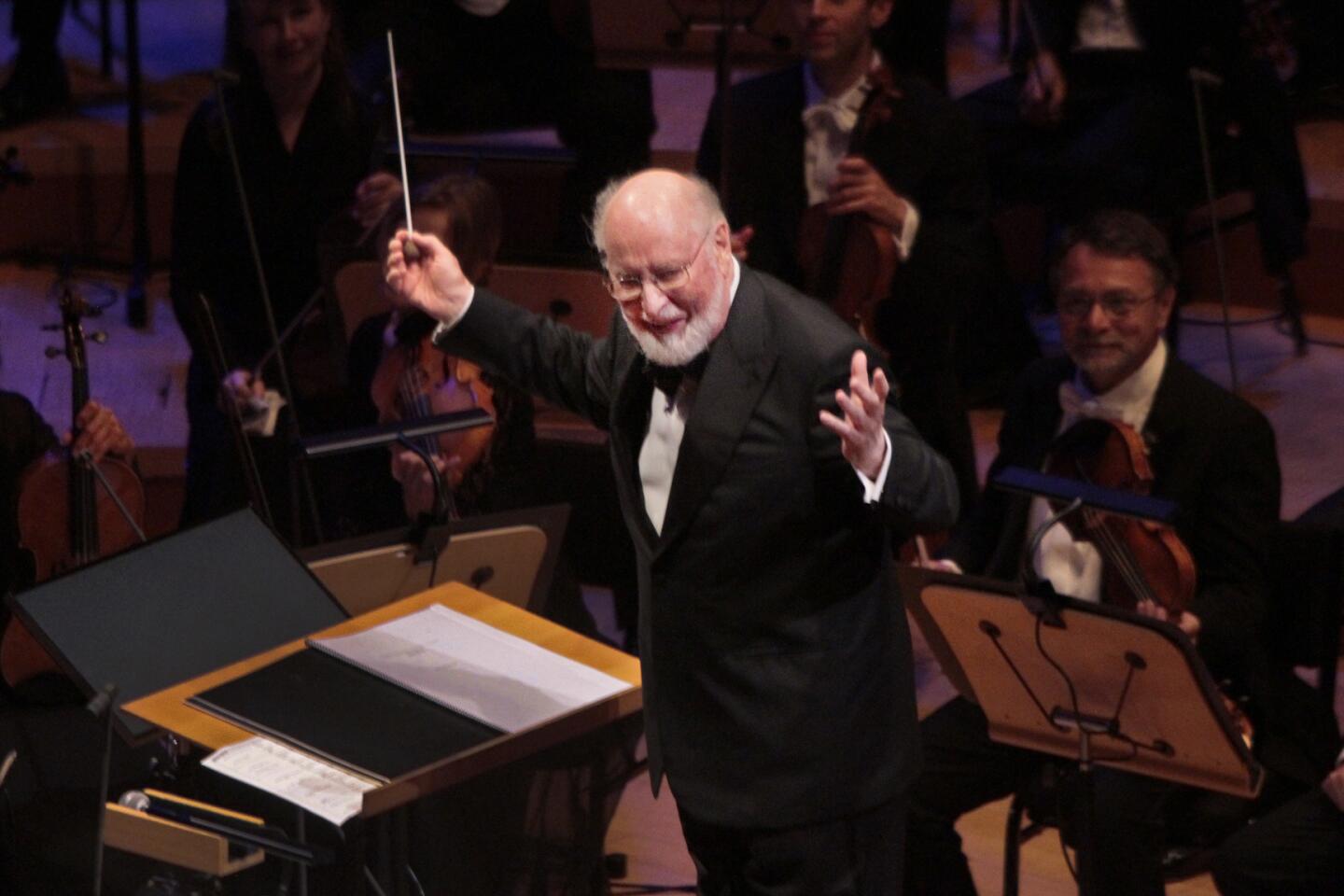

When Williams finally came on stage in triumph to conduct the “Star Wars” Imperial March, suddenly the crowd, far more oldsters than youngsters, tittered like kids when a costumed Darth Vader made an appearance.

Williams, who is a vigorous 82, has been lauded for ages. More celebrations are evitable. But this unexpectedly great gala was — with the exception of Perlman and an unprofessionally distracting camera crew filming for a future PBS broadcast – extraordinary.

You didn’t have to be a fan.

Twitter: @markswed

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.