Column: Race, inequality, polarized politics: Why Shakespeare’s 1623 First Folio matters in 2016

- Share via

A precious First Folio of Shakespeare plays, one of several on tour from the Folger Shakespeare Library, has arrived at the San Diego Central Library, where it will remain for the next month in a glass case under the watchful eye of a friendly (but don’t test him) security guard.

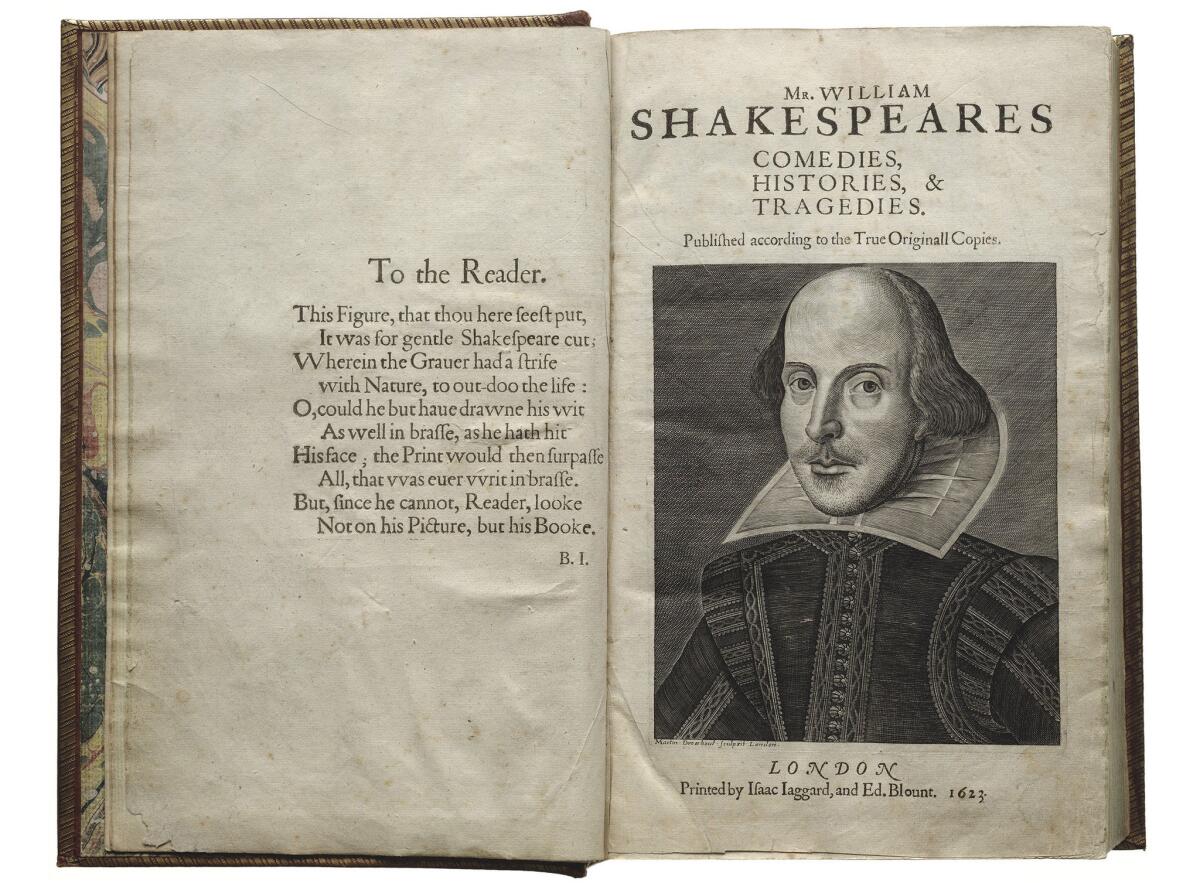

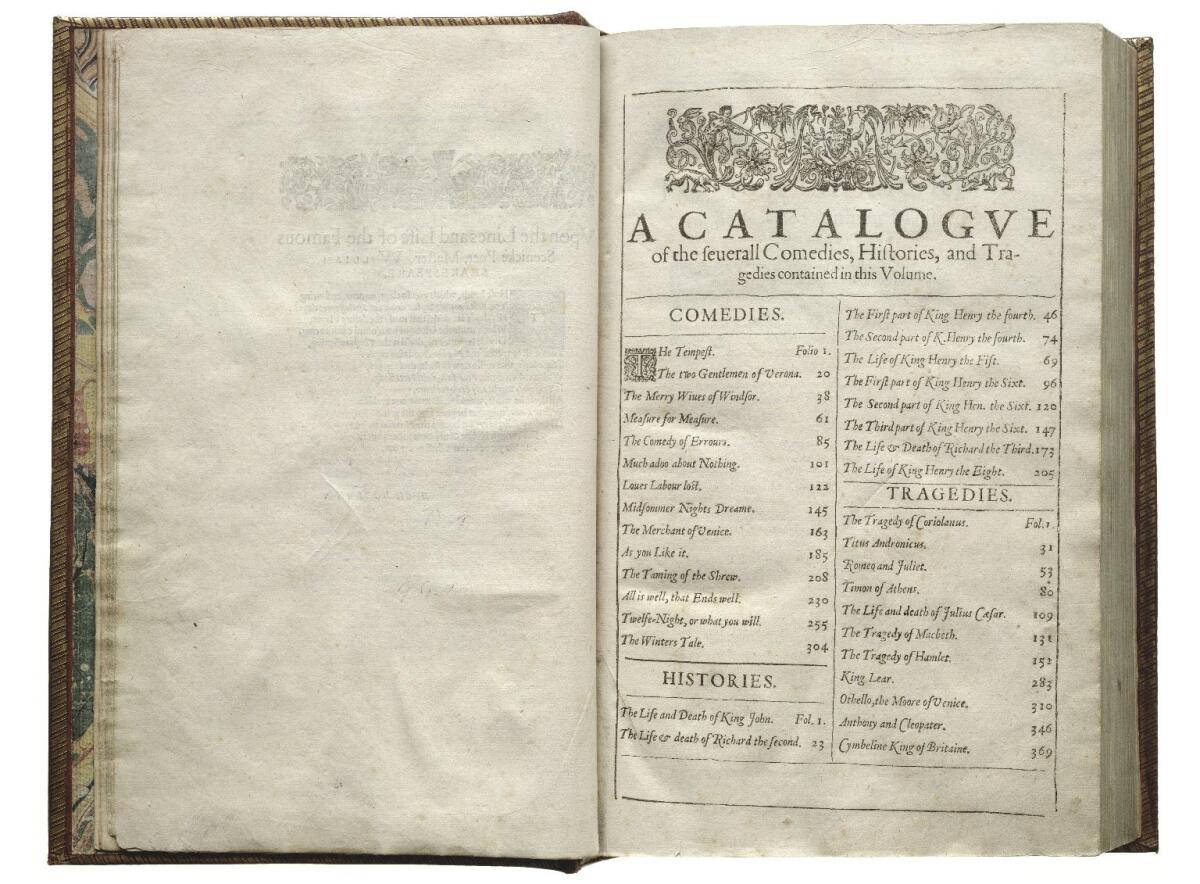

This volume of 36 plays from 1623 represents the first collection of the author’s dramatic writing. Many of the dramas, including “Macbeth,” “As You Like It” and “The Tempest,” were published for the first time in this edition. Without this publication, some of the greatest masterpieces of dramatic literature might have been lost.

Naturally, the book is opened to Hamlet’s “To Be or Not to Be” speech, the most famous soliloquy in all of Shakespeare. The Old Globe Theatre, which is co-hosting this leg of the journey with the San Diego Public Library, has contributed to the exhibition, putting on display costumes, props and programs from its rich history of producing Shakespeare in San Diego.

A citywide smorgasbord of lectures and public events has been organized around the First Folio’s visit. There was a glamorous kickoff on Saturday at the Old Globe’s open air Lowell Davies Festival Theatre. The program, Shakespeare in America, was hosted by Old Globe artistic director Barry Edelstein, renowned Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro (editor of the anthology “Shakespeare in America”) and theater writer Jeremy McCarter.

Integrating historical material with scenes from Shakespeare’s plays and musicals adapted from his works, the bill featured a glittering roster of talent that included Blair Underwood, Hamish Linklater, Lily Rabe and Alfred Molina. It was an elegant and edifying celebration of Shakespeare’s enduring vitality in America.

This is the only California stop for “First Folio! The Book That Gave Us Shakespeare,” the national road show commemorating the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, and it’s receiving all the pomp and circumstance of a state visit from one of the more popular members of Britain’s royal family.

Some may wonder whether all this fuss over an old book is just another outbreak of Bardolatry, the fetishization of all things Shakespeare. There are, after all, a number of First Folios in the Los Angeles area. The Huntington in San Marino has four, one of which is on display in the impressive library exhibition of rare books — an attraction no one visiting the botanical gardens or art collections should pass up.

Others may question whether at this point in our cultural life, when we’re openly wrestling with issues of diversity and inclusiveness, we should still be polishing the crown of this long-reigning Dead White Male Author. But the way I see it, this traveling exhibition has come at just the right time.

As Shapiro pointed out in his remarks on Saturday, Americans throughout their history have sought reflections of their national identity in Shakespeare’s plays. This isn’t as far-fetched as it may sound: Issues of race, immigration, economic inequality and political polarization challenge Shakespeare’s characters just as they continue to test us today.

American leaders, such as Abraham Lincoln (a compulsive reader of Shakespeare), have turned to the dramas for eloquent counsel in times of crisis. In an era when public discourse has become so debased, Shakespeare urges us, if not to a higher standard of civility, then to a more vivid, witty and intelligent use of language.

The story behind the First Folio, which came out seven years after Shakespeare’s death, opens a window onto the way authorship is processed and transmitted. But the plays are undeniably the thing, and anything that brings us closer to them performs an invaluable service.

We know relatively little about Shakespeare’s life. This has led to an avalanche of speculative biographies and an alternative universe of conspiracy theories casting doubt on Shakespeare’s identity.

There are people who find it unfathomable that a provincial man lacking a university education and aristocratic polish could possibly have been the author of these great plays. But Shakespeare proves that we are more than our social identity.

A compilation of the known facts of his background can contextualize but never fully account for his genius. Shakespeare bestows the same range of possibilities to his characters, who retain a degree of mystery even as their histories and psychologies are illuminated.

It may be hard to determine where Shakespeare came down on the burning controversies of his day, but we do know the pattern of his thought from the record of his plays. His worldview was stubbornly undogmatic. No writer challenges the ideological approach to life with the potency of Shakespeare, whose characters are too unpredictably human to be reduced to theoretical schemes and doctrinaire beliefs.

Norman Rabkin, who was a UC Berkeley English professor, wrote a brilliant book called “Shakespeare and the Common Understanding” (1967) that elegantly formulates Shakespeare's habit of structuring his plays around competing systems of value.

“The technique of presenting a pair of opposed ideals or groups of ideals and putting a double valuation on each is the basis of Shakespeare’s comedy as well as his tragedy, and it is clearly the source of a good deal of his power,” Rabkin observed.

It is this dialectical vision, in Rabkin’s view, that puts the plays “out of the reach of the narrow moralist, the special pleader for a particular ideology, the intellectual historian looking for a Shakespearean version of Renaissance orthodoxy. Indeed, it is that mode of vision that puts the plays beyond philosophy and makes them works of art.”

This is what has allowed us to read the conflicts and contradictions of our own society in Shakespeare’s works. Rather than positing answers, his plays present an active debate that invites us to pick up the discussion in our own age.

THE THEATER OF TRUMP: What Shakespeare can teach us about the Donald »

So even though our values have evolved in crucial areas beyond those of Shakespeare's era, we can talk back to the plays because they talk back to themselves. Whether it’s sexism in “The Taming of the Shrew,” racism in “Othello,” anti-Semitism in “The Merchant of Venice” or colonialism in “The Tempest,” it is hard to find a point of view that Shakespeare hasn’t already anticipated and embodied.

“The Taming of the Shrew,” an early comedy that can make us cringe at the endorsement of an antiquated gender hierarchy, is being presented right now in New York by the Public Theater’s free Shakespeare in the Park with an all-female cast that includes Janet McTeer as Petruchio and Cush Jumbo as Katherina. It is safe to say that if Kate wasn’t such a formidable force and if Shakespeare wasn’t so perceptive about the power of physical attraction and the unruly nature of romantic love, that the play would not still be provoking these new modes of exploration in the 21st century.

The Holocaust didn’t end productions of “The Merchant of Venice.” If anything, it urged us to inquire more deeply into Shylock’s character, to hear his report of being spat upon by the Venetians not as an incidental remark but as an appalling testimony to his outsider status, and to understand with greater sympathy his question, “Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions …?” To see him, in short, as both tragic figure and comic villain.

“Othello” gives voice to noxious racial attitudes, but this Moor is sensitively understood in a way that transcends the racial thinking of early 17th century England. The role remains a gift to actors: Two of the greatest performances I’ve seen in the last decade were the Othellos of Chiwetel Ejiofor and Adrian Lester.

The examples of Shakespeare’s lasting legacy are legion — and not inexplicable. Virginia Woolf once wrote, “To write down one’s impressions of ‘Hamlet’ as one reads it year after year, would be virtually to record one’s own autobiography, for as we know more of life, so Shakespeare comments upon what we know.”

With their vision of humanity crossing national borders with the impunity of trees, the plays reveal to us the journey of our society as well as of our souls. Four hundred years after Shakespeare’s death (an occasion Edelstein happily reframed as “the 400th birthday of his posthumous reputation”), his work continues to light our path.

The excitement over this First Folio visit only confirms the prophetic truth of Ben Jonson’s words memorializing his greatest contemporary: “He was not of an age, but for all time!”

MORE:

'Juliet and Romeo'? Royal Swedish Ballet gives Shakespeare a twist at Segerstrom

The theater of Trump: What Shakespeare can teach us about the Donald

'Hamilton' star Lin-Manuel Miranda joins James Corden for 'Carpool Karaoke'

Meryl Streep lampoons Donald Trump — but has she already mocked Hillary?

Follow me @charlesmcnulty

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.