Hollywood ‘spec script’ is making a comeback

- Share via

Independent producer Lawrence Grey sold the screenplay for “Section 6” for $1 million after setting off a bidding war between the major studios.

Six months later, in March, he sold the screenplay for “Winter’s Knight” the same way, for the same price.

The sales of the speculatively written properties, both of which Grey will produce, put Hollywood on notice that the “spec script” was on the rebound and reminded some executives of the 1990s, when $1-million-plus spec sales were common.

Movie studios, then flush with money, were pumping out more than 20 films a year and constantly in search of new material. Specs were coveted because they enabled studios to circumvent the often costly and time-consuming development process.

BEST MOVIES OF 2013: Turan | Sharkey | Olsen

Big sales such as the $3-million purchase of Joe Eszterhas’ “Basic Instinct” and the $1.75-million acquisition of Shane Black’s “The Last Boy Scout” touched off a decade-plus of freewheeling spending.

But as studios stockpiled material, says J.C. Spink, a veteran manager and producer who has worked in the spec market for years, “they were buying so much material that they didn’t make that they began to think, why are we doing this?”

By the mid-2000s, the spec market was in decline — with studios rolling the dice less often on screenplay purchases, relying instead on relatively safer projects, often tied to popular books, comics or other properties. Then the 2007-08 Writers Guild of America strike decimated the market.

But according to data from the website the Tracking Board, which covers the spec world, the market is improving. Although just 67 spec scripts were sold in 2009, 154 were sold in 2012 and 182 were sold in 2013 — but just four, excluding “Section 6,” traded hands for $1 million or more last year.

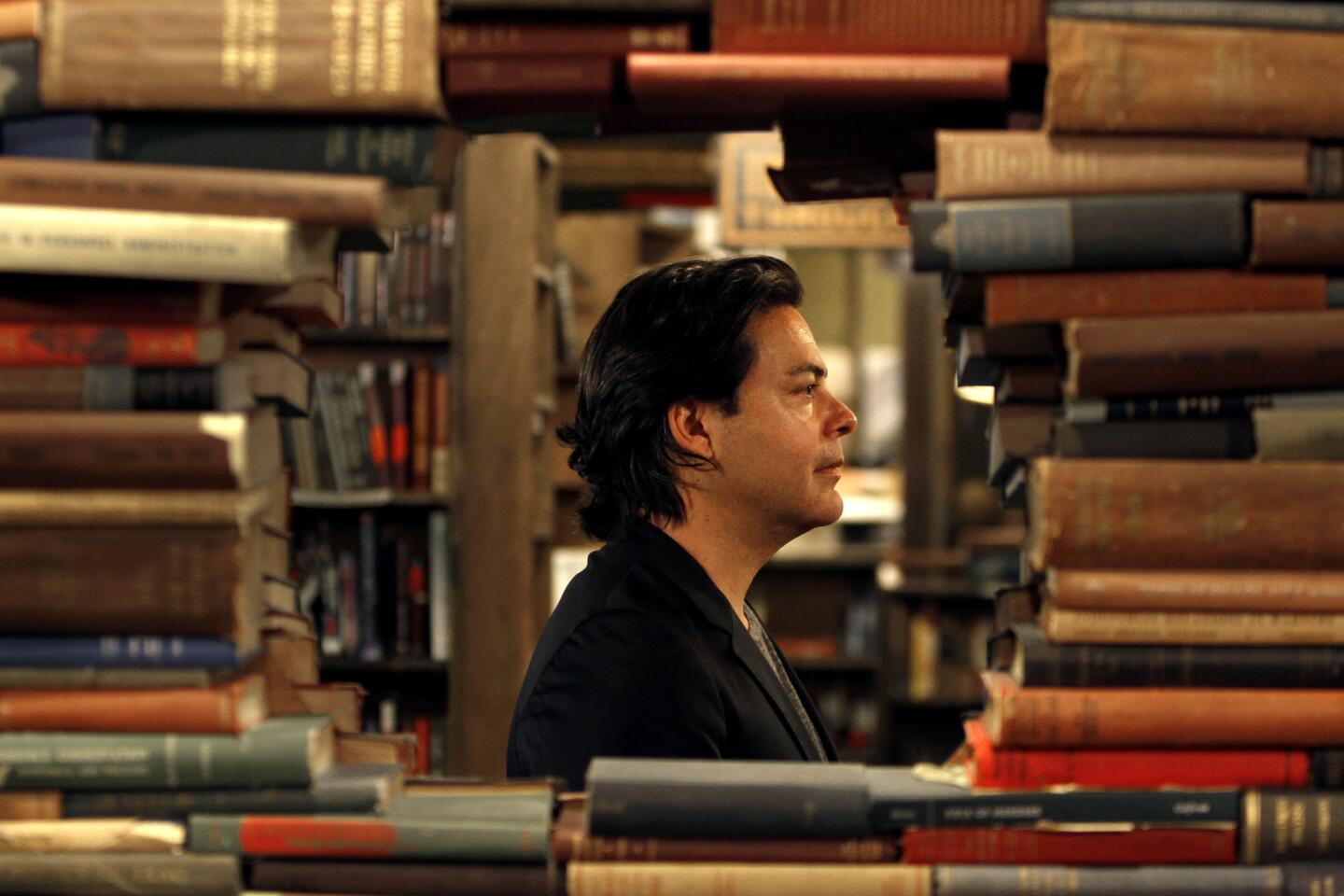

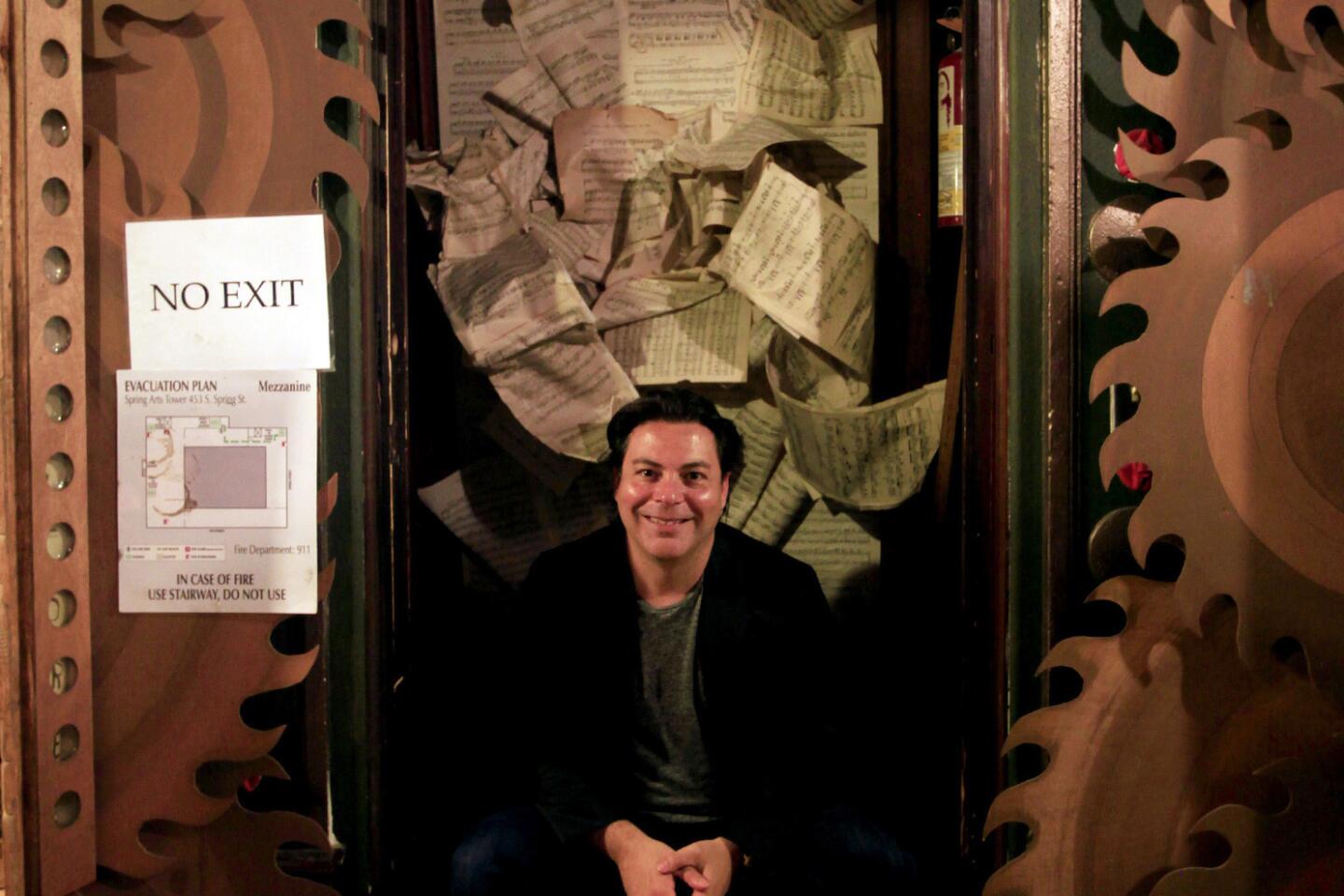

Grey, 43, grew up in Montreal, graduated from Georgetown Law School in 1998 and got his start in Hollywood working as an unpaid intern for producer Scott Rudin.

PHOTOS: Box office top 10 of 2013 | Biggest flops of 2013

Later, he rose to production executive, working at Zucker/Netter Productions, then Fox Searchlight Pictures and later Universal Pictures. After he lost his job as senior vice president of production at Universal in January 2009 during a round of corporate downsizing, Grey joined Mandate Pictures, for whom he produced “Hope Springs” and “Last Vegas.” But Grey soon decided to strike out on his own.

He would rely on a talent for finding great material.

While working at Fox Searchlight Pictures in the early and mid-2000s, he discovered the spec script for the Academy Award winner “Juno.”

At Zucker/Netter Productions, working for “The Blind Side” producer Gil Netter, he spearheaded the acquisitions of spec scripts for “Phone Booth” and “Dude, Where’s My Car?”

Over the years, he even developed a trick for getting access to the best material before other companies — by currying favor with workers who manned the talent agency photocopying rooms with bottles of Macallan whiskey.

“When they got an order to print a spec script, I would be the first to know,” Grey said.

PHOTOS: Stars who turned down, or were turned down for, ultimately famous roles

Transitioning to life as an independent producer, he realized it was hard to get his hands on scripts ready to be shopped to major studios.

Grey, who founded his Grey Matter Productions in January 2013, cast his lot with a handful of hungry, malleable writers willing to work closely with him on revising their projects.

“Working with Academy Award-winning writers is hard if you are a new guy,” he said. “I really wanted to come up with some things that I felt were great and pick my winners and lean into them.”

Those writers wound up selling their stories for seven figures. But first they had to go through the wringer with Grey, who prides himself on an intensive development process that observers say isn’t the norm these days, with many producers focused on projects based on proven intellectual property.

“He knows what he wants and he goes after it hard,” said Aaron Berg, whose “Section 6” was sold to Universal Pictures for $1 million and centers on the true story of the founding of British intelligence agency MI6.

Michael De Luca, co-president of production of Columbia Pictures, a unit of Sony Pictures, said Grey’s approach isn’t new — but not as many independent producers are doing it these days.

“It used to be called producing. Period,” said De Luca, who along with Andrea Giannetti, Columbia Pictures’ executive vice president of production, spearheaded Sony’s $1-million purchase of the Santa Claus origins tale “Winter’s Knight,” which was written by Ben Lustig and Jake Thornton. “You lived by your wits and you developed ideas. It’s a very important skill set, and the producers that do it and do it well will always get traction in the marketplace.”

Despite signs of new life for spec scripts, veterans don’t expect the market to ever be what it was.

GRAPHIC: Faces to watch 2014 | Entertainment

“I don’t know if it’ll ever come back to the way it was when I was doing it,” said Alan Gasmer, a manager and producer Vanity Fair once dubbed the “spec king” for his work at William Morris Agency during the spec boom years. “It’s a different environment, but I think the studios have learned their lessons and are more open to original material.”

Grey acknowledges that it will be harder to find time for intensive script development now that his profile has been upped and he has access to more material. And his schedule would be further complicated once his movies go into production, because he will be on the set.

Also, Grey knows that his business model, as it stands, is risky because if a project he’s nurtured for months founders, he’s left with little recompense.

But Grey will take his next spec script to market within two months. He is working with writers on developing a television pilot and two features, and other projects are on deck.

Grey said he isn’t “expecting to bat 1000,” and he realizes that sticking to his guns means he could wind up missing out on some projects. But he’s OK with that.

“It’s going to mean I am going to probably pass or not get involved in stuff that is going to sell,” he said. “Other producers will be excited, but … it’s important to me to maintain the business model.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.