I played ‘Slave Tetris’ so your kids don’t have to

- Share via

I knew something was wrong when I found myself doing doughnuts in a fully loaded slave ship off of Ivory Coast.

During the past week, an educational game aimed at elementary and middle school students titled "Playing History 2 — Slave Trade" has been the subject of online controversy over a brief segment that involved puzzle-stacking the bodies of cartoon slaves inside a ship. This earned the game the nickname "Slave Tetris."

Part of a series of educational games by the Danish company Serious Games, "Playing History 2 — Slave Trade" was released in Europe in 2013 but didn’t provoke outrage until it was added to the online gaming store Steam late last month. Accusations of racism were leveled against Serious Games by Twitter users in the U.S., and soon the outcry was international.

In response, the Danish company removed the "Tetris"-like segment (though references to "stacking" slaves still exist), tweeting that "it was perceived to be extremely insensitive by some people."

But why was the slave-stacking mini-game originally included in "Playing History"? And is the rest of the game as bad as the "Slave Tetris" portion, which sounds like something racist Internet trolls would make? Is removing just one section of this game enough?

To find out, I decided to play the game from start to finish and try to make sense of what was conceived as a legitimate teaching tool.

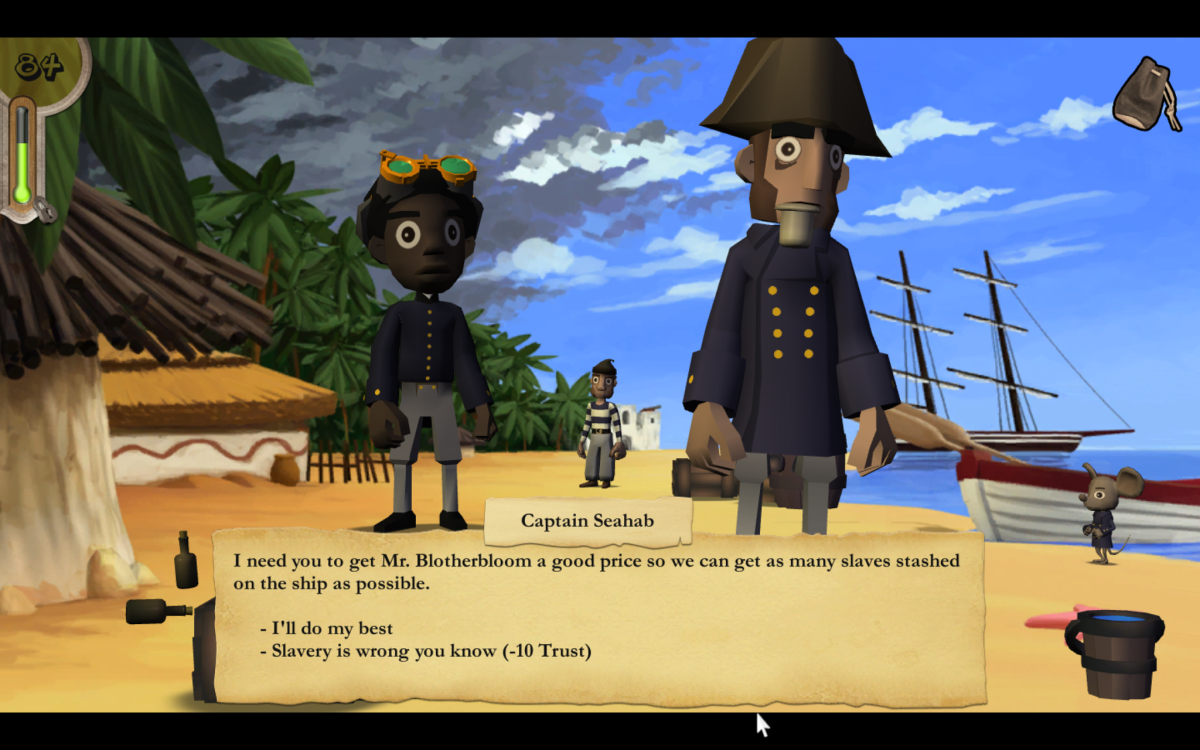

First, some background: In the game, you play as a young slave boy named Tim, who must help his master, a slave ship captain, buy 300 slaves and transport them to the Americas. Along the way, you discover that your sister is being sold as well. Instead of taking the guns and rebelling or freeing her immediately, you stuff her into a slave ship and sail her across the Atlantic.

Yes — you, a black slave, pilot the slave ship. Twice. To "win" this section, you are literally tasked with being a good slave driver. As time expires, your boat runs out of rations. So you need to steer the boat, avoid wind blasts that blow you off course, and collect items that replenish your food gauge.

If you try to go back to Africa, you fail. If you don’t sail your boat fast enough, you fail.

But whether you make the trip successfully or not, you have the option of playing through the segment again — over and over. This portion is all about the fun of scooting around on a boat as a ship captain. "Winning" here means getting all of the slaves (including yourself) to America.

The most disturbing thing is that this is one of the most engaging and "fun" parts of the game.

It reminded me of playing "The Oregon Trail" in the third grade on an old Apple IIe that we had in the back of the classroom at my elementary school. That game is supposed to teach you pioneer life on the frontier (while leaving out the massacre of Native Americans). But at that time, I didn’t really care if Mary-Sue got dysentery or if the river was too high to ford. As a third-grader, all I wanted to do was to get to the hunting scene, where you get to shoot bears and squirrels. "The Oregon Trail" anticipated this, though, and made the hunting scenes a reward that you could enjoy only if you managed your resources properly.

That’s where this slave boat race fails. It’s as if "The Oregon Trail" had a special mode that let you skip all the historical education and just shoot bears, on repeat, forever. Except this time, you schlep around black people while collecting icons of cakes and wine — delicacies that the slaves below deck are certainly not eating.

Somehow, this part of the game has escaped media attention. Serious Games has had to answer for only the "Slave Tetris" portion. According to a statement posted on the Steam forums from Serious Games Chief Executive Simon Egenfeldt-Nielsen, the slave-cramming mini-game was intended to be "insensitive and gruesome," in order to teach about slavery effectively. "The reactions people have to this game," he continued, are "something they will never forget, and they will remember just how inhumane slave trade was."

Would a young player be able to grasp the inhumanity of the slave trade, all while being rewarded for stacking brick slaves efficiently or expertly navigating a slave ship?

Allie Jane Bruce, a children’s librarian at the Bank Street College of Education in New York, doesn’t think so. I called her to ask if she would recommend a mini-game like "Slave Tetris" to teach kids, and before I could finish the question she interrupted me: "Slavery should not be fun."

Bruce, who works with children in the game’s target audience group, said that even if students had "unforgettable" realizations of the true nature of slavery, the use of a fun mini-game to teach this is very "white-centric." Black students, she said, would not need the experience of playing a Tetris-like game to realize that slavery was inhumane.

"Put yourself in the shoes of a black child," Bruce said, "watching their white classmates playing Tetris with people that look like you. Even if the classroom was all black, what kind of image is that, seeing yourself played with as a Tetris block? It’s wrong on so many levels."

Even without the now-removed section, the educational value of the game itself is debatable.

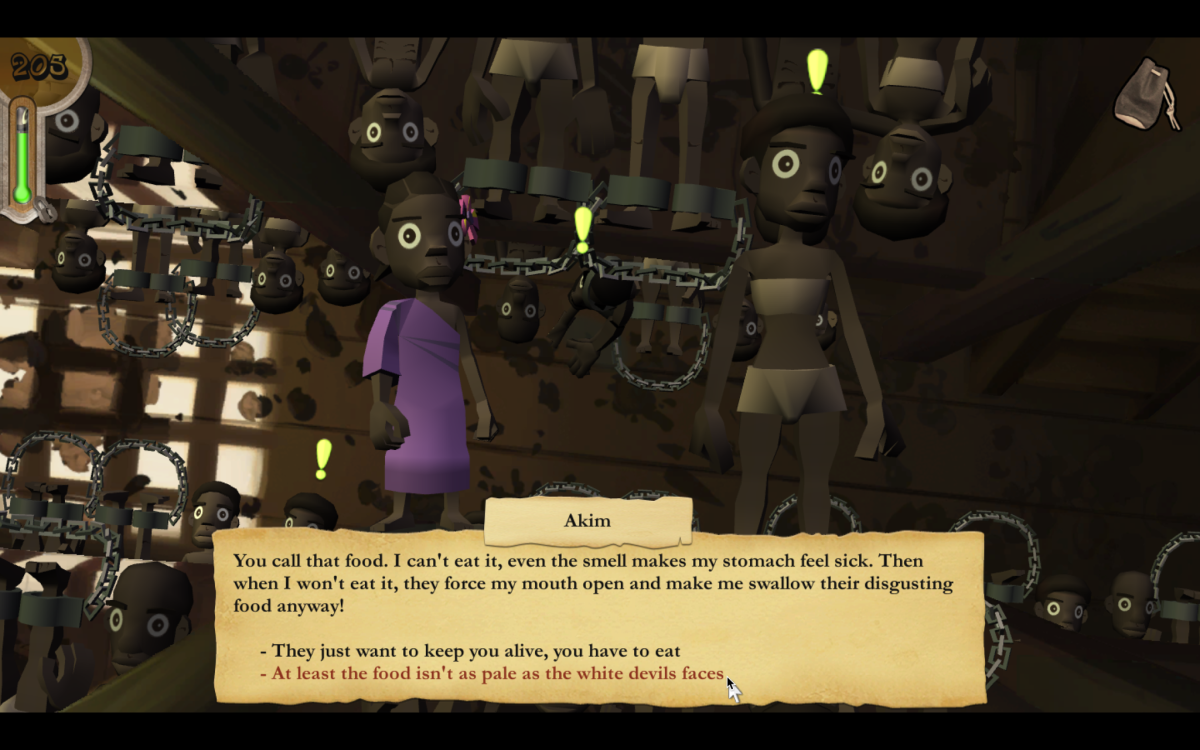

In a game that claims to portray horrors of the transatlantic slave trade, the slave owners in "Slave Trade" are pretty nice. If you complete a simple task for even the meanest white person, they are kinder to you. In fact, some of the rudest characters in the game are not white slavers but black slave characters, who sometimes refer to white characters as "white devils."

The most sympathetic character in the game is Doctor Eagleledge, a kind old white man whose job is to keep the crew and cargo of the slave ship healthy. He calls the protagonist Tim by his original African name, Putij (but only when other white people aren’t around), and seems to exist mainly to show the player that not all white people were bad. Eagleledge offers to write to King George about the poor conditions of slave ships, but he never takes any real action himself. Instead, he offers distractions, telling your character that "the only way to forget the horrors is to think of something else, like poetry."

Eagleledge’s line turns out to be a theme of the rest of the game. "Slave Trade" occasionally hints at the cruelty of slavery but quickly drops the topic for lighter conversation.

That’s not to say there is no historical accuracy in the game. Any young player who finishes "Slave Trade" will know what scurvy was, that some slaves died during the the trip from West Africa to the Americas, and how long that voyage took.

But other facts risk being misconstrued.

In an African village, your character gets into an argument with an African man who is angry at you for collaborating with the white slavers. But your character argues back and tells him, "You’re not exactly angels, either," because they are selling slaves to the whites. It’s strange that this is in the game at all. It reduces slavery to a story of "bad people" on both sides doing bad things and ignores the structure of violence and racism that allowed slavery to happen.

Another troubling part of this game is the point system. Help your master bargain with locals to bring down the cost of slave children and you’re rewarded with points. But if you lie to your master to help a slave, you risk losing "Trust Points." If you comply immediately, you can avoid this penalty. In general, the game won’t proceed until you comply, so if you want to do "well," you quickly learn to do as you are told. The moral lesson seems to be: Bide your time, be polite, and endure — or in other words, be a good slave.

At the end, you help other slaves escape captivity. This is a "happy ending" and possibly what a young gamer might expect. But it serves to lighten the mood in a game that is probably too light to begin with, considering that it already includes a comic-relief caricature named Susu, the spear-wielding, bare-chested African who cracks lines like Mr. T’s classic "I pity the fool."

In an emailed statement to The Times, Serious Games CEO Egenfeldt-Nielsen said that the game was never intended for the U.S. market. He estimated that "around 5-10% of Danish schools have used" the "Slave Trade" software in the classroom and said that "in general the feedback has been that it is a useful educational tool."

He also said that the game was not intended to be a stand-alone experience. Serious Games sent me a copy of supplementary print-out materials provided for teachers and students to use along with the game.

To be fair, these materials would round out the learning experience considerably. Students are asked to not only answer factual questions about the triangular trade but more open-ended questions, such as "What kind of view of humanity is slave trading based on?" That’s an excellent, nuanced question — but one that a slave ship boat race mini-game would probably not help to answer.

Other educational games have tackled slavery as a theme, but they have fared better, at least in the eyes of critics. "Mission US" is a free online educational game that includes a section on slavery and has seen some mixed reviews but is otherwise rated highly both by advocacy groups and gaming sites like Kotaku, which praised the game for "[treating] its characters and its players with respect." Like "Slave Trade," "Mission US" includes a selection of downloadable PDF "educator guides" for teachers to follow as they teach.

The topic of slavery also turns up in fictional, story-based games. "Thralled" is a puzzle game with a story about a runaway slave in 1700s Brazil who has been separated from her newborn child. The game has not yet been released, but reviews are also positive: Gaming site Polygon called it "beautiful and heartbreaking." "Slave Trade" is neither.

At the same time, the public bashing of "Slave Trade" — with online commenters pointing indignantly at the "Tetris"-styled portion or cracking jokes about it — is an all too easy way to publicly posture against overt racism. It is unlikely that the game will ever be used in any U.S. classroom, which makes it a safe target.

But we are raising a generation of children in Texas where, in 2015, the State Board of Education has in effect declared that slavery was just a side issue in the Civil War and where textbooks are not required even to mention Jim Crow or the Ku Klux Klan. Those kids will grow up to be parents, teachers, governors, or maybe even presidents.

Some of us seem to be comfortable condemning a foreign-made indie game that few will ever play. Even conservative sites like Breitbart have jumped on the train. But when our own public institutions attempt to whitewash our own history, we are a bit more hesitant with the criticism. That, to me, is dangerous.

My hope is that the uproar over this silly game will encourage us to question our own learning materials and keep the conversation going about how we teach our own history.

Twitter: @dexdigi

MORE:

Happy 30th, 'Super Mario Bros.,' and thanks for the lessons big and small

'Volume' brings a rebellious heart to video game trends, turns class warfare up a notch

Cinematic 'Until Dawn' sets its sights higher than typical horror fare

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.