How hip-hop fashion went from the streets to high fashion

- Share via

For his fall 2017 women’s fashion show, designer Marc Jacobs sent models down a stripped-down runway at New York’s Park Avenue Armory last February, wearing tracksuits topped with thick gold chains, retro-style coats and eccentric headwear, a hat tip to hip-hop’s early days in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

Jacobs’ collection was inspired, he said, by two things: the 2016 Netflix documentary “Hip-Hop Evolution,” which chronicles the music genre’s rise from the ’70s through the 1990s, as well as memories from his own New York childhood.

“This collection is my representation of the well-studied dressing up of casual sportswear,” the designer explained in a statement at the time. “It is an acknowledgment and gesture of my respect for the polish and consideration applied to fashion from a generation that will forever be the foundation of youth culture street style.”

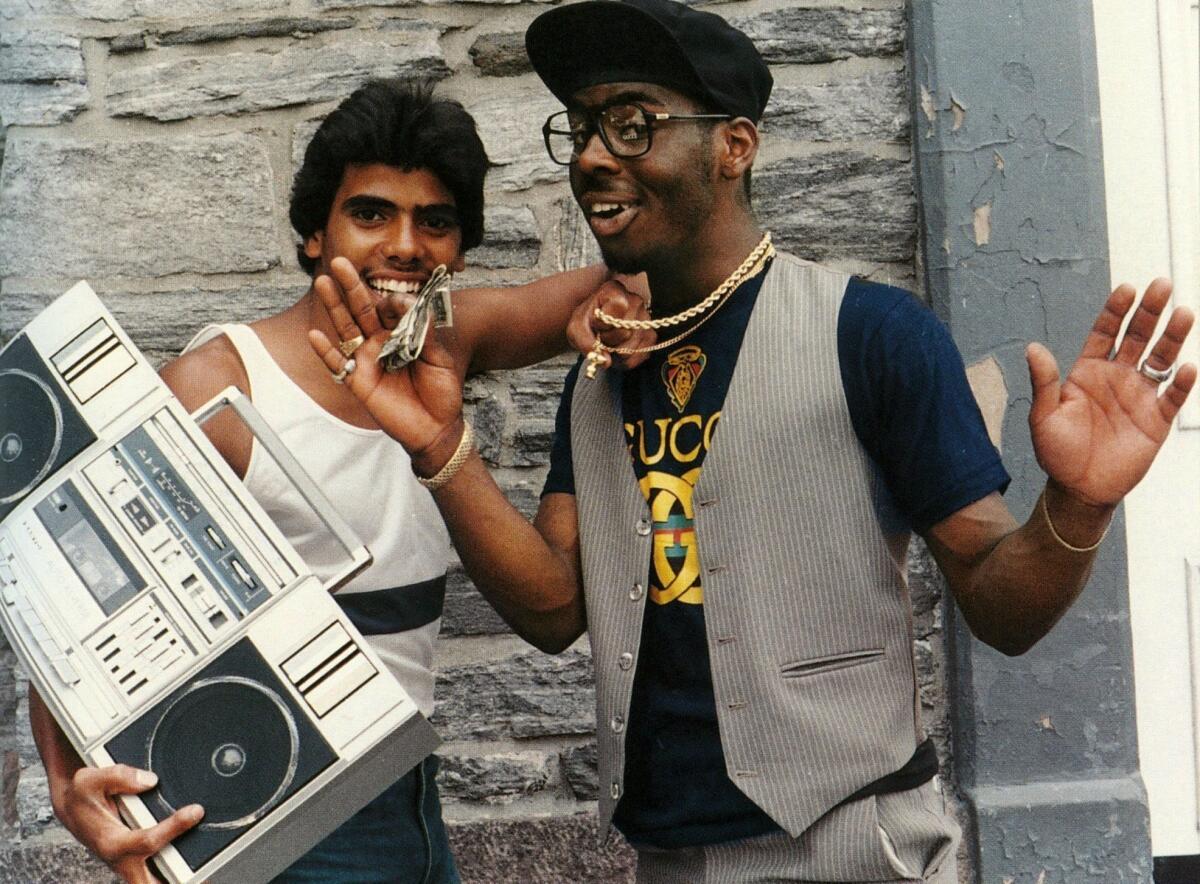

That’s just one example of how hip-hop and high fashion have become deeply intertwined since the 1970s. In the 1980s and ’90s, hip-hop stars Run-DMC, LL Cool J, Salt-N-Pepa and others put their personal style on display. And today, no one bats an eye at rap star Kanye West’s much-hyped Yeezy line of apocalyptic-themed apparel and accessories for Adidas or clutches their pearls when rapper ASAP Rocky stars in advertisements for Dior Homme or Calvin Klein.

While the hip-hop community has long been enamored with the fashion world, the appreciation has been reciprocated in recent years as luxury labels including Balmain and Saint Laurent embrace hip-hop artists and mimic some of their aesthetics.

When you don’t have much ownership over where you can land in society, your financial situation...the one thing you can control is the way you look.

— Sacha Jenkins, "Fresh Dressed" film director

The same can be said for luxury Italian brand Gucci’s partnership with Dapper Dan, the underground Harlem designer who made flashy clothing featuring the recognizable logos of Gucci, Louis Vuitton and other labels cult hits despite (or perhaps, because of) his wares’ dubious origins as knockoffs.

With Gucci’s support — and after the Italian label sent a jacket down the runway similar to one of Dapper Dan’s original creations and called it an homage — the so-called knockoff king late last year reopened his boutique, which had closed in 1992. Together, Gucci and Dapper Dan have plans to release a capsule collection this year.

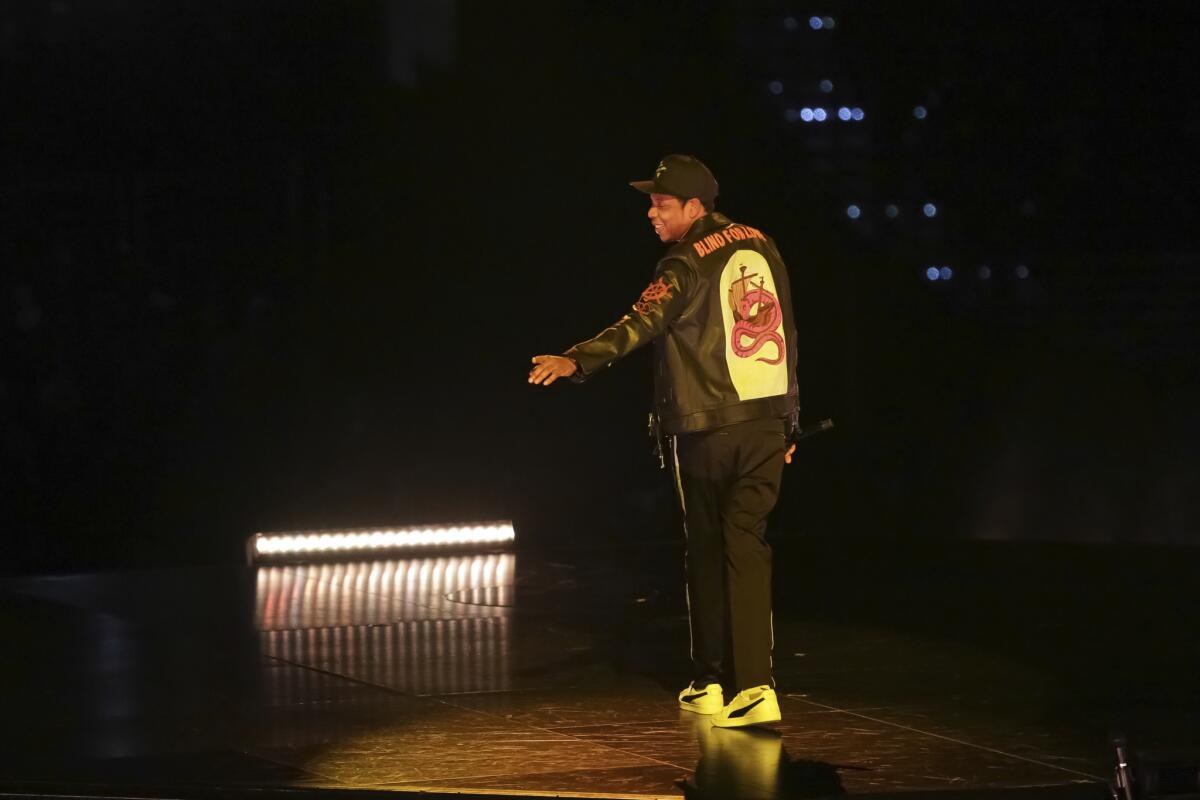

In recent seasons, an onslaught of hip-hop fashion styles — baggy pants and nostalgic ’90s athleticwear — have populated high-end European and American runways, another sign of how hip-hop and fashion influence each other. (For example, Jay-Z wrote the song “Tom Ford,” a nod to the fashion designer, for his 2013 “Magna Carta Holy Grail” album. Ford returned the shout-out by sitting Jay-Z and his wife, Beyoncé, front row at his fall 2015 runway show in Los Angeles.)

This year’s list of Grammy nominees makes it clear: hip-hop as a musical genre and the artists who populate the industry are at the center of culture. And beyond awards shows, hip-hop players such as Nicki Minaj, Drake, Cardi B, Pharrell and others now dictate major pop-culture and fashion trends.

However, it wasn’t long ago that hip-hop was warily looked at as an insurgent movement tinged with danger, particularly with the rise of Compton’s N.W.A and the East Coast/West Coast rap rivalry, thus making the genre a hard sell for any overlap with luxury brands. During those early years, hip-hop artists weren’t necessarily seeking a place in the luxury fashion world. But image, how one displays himself or herself through style choices, has carried a certain level of social capital in the black community.

“Fashion has always been an important part of the hip-hop identity because fashion has always been an important part of black identity in America,” says producer and filmmaker Sacha Jenkins, director of the 2015 hip-hop fashion documentary “Fresh Dressed.” “Because when you don’t have much ownership over where you can land in society, your financial situation, your educational situation, the one thing you can control is the way you look.”

Plus, there’s a celebratory aspect to looking good, one that mirrors hip-hop’s ability to find a thread of joyful rebellion embedded in life in disenfranchisement. “Having great fashion was a way to express yourself and to show off,” says Elena Romero, an adjunct assistant professor at the City College of New York and the author of “Free Stylin’: How Hip Hop Changed the Fashion Industry,” adding there was a deeper hidden message. “Fashion was a way to showcase your aspirations or your abilities to make it or make it out.”

Stylist Matthew Henson agrees. “Our culture has aspects that are rooted in looking good despite having little to nothing to work with and making the best of it, and this comes from the church experience,” says Henson, who works with artists including A$AP Rocky. “You wear your best. That transcends to now — being proud of your appearance. Not only be good at what you do, but you have to look the part to be seen as an equal.”

While the final sartorial result might appear spontaneous, looks were planned and executed with startling precision — a mirror to hip-hop’s prolix rhymes delivered with casual ease. Possessing good taste, in certain pockets of L.A. or New York, could be viewed as transformative to a community that was systemically overlooked. Innate style was something that money couldn’t necessarily dictate.

Hip-hop’s initial outsider status allowed the genre a certain freedom and playfulness that has since gone from exception to rule. Today, streetwear dominates; track pants and hoodies are the new suit and tie, and slim silhouettes have given way to a looser, slouchy one. Sneaker culture, often tied to hip-hop culture, has also exploded, with websites dedicated solely to chronicling the minutia of casual footwear.

Hip-hop artists presented this relaxed fashion reflecting life on the streets to the masses, first through television (MTV videos and “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air,” starring rapper-turned-actor Will Smith, were touchstones) and, years later, through the internet and social media. Today, just look at brands such as Valentino with its spring 2018 ready-to-wear collection filled with louche tracksuits and Balenciaga’s sporty four-figure windbreakers as being examples of hip-hip’s trickle-up effect.

More important, all of this is the foundation for a new generation of fashion labels including Public School and Los Angeles-based John Elliott, led by fashion entrepreneurs who aren’t just adopting hip-hop postures as a trend but using them because they embody the milieu in which they grew up.

Perhaps most crucially, it’s hip-hop’s use of reinvention that was most prescient of today’s style of dress. The idea of remix culture has been a core tenet of hip-hop music, taking existing musical motifs and mixing them together to forge a new sound. That ideology has extended to the genre’s visual presentation as well.

In hip-hop, it’s common to wear high-end or preppy clothes mixed with oversized sportswear items. That ethos of anything goes — mixing high and low, ironic and serious — is now industry standard and, in many ways, it reflects a world defined by the cut-and-paste randomness of life in the internet age.

“I think people of color, poor people in America are masters of the remix,” Jenkins says. “Like Dapper Dan who reimagined these luxury brands that weren’t necessarily tailored for us. He re-imagined them in a way that spoke to our identity and the way we wore clothes.”

The Age of Hip-Hop

From the streets to cultural dominance

The 2018 Grammy nominations are overdue acknowledgment that hip-hop has shaped music and culture worldwide for decades. In this ongoing series, we track its rise and future.

While mass culture has leaned toward hip-hop culture, it didn’t start this way. “In so many ways, hip-hop is a reflection of society and environment, wherein folks who are denizens of the culture, do not see themselves, do not see themselves in mainstream culture,” Jenkins says. “So they say, ‘How can we see ourselves in our own terms while borrowing the things we appreciate — even if these brands don’t appreciate us?’” That defiant attitude and desire to reinterpret styles serves as a foundational principle of hip-hop fashion that has crossed into the mainstream.

Perhaps one of the greatest lessons hip-hop has taught the fashion world has been every man is a brand. Hip-hop artists have learned quickly that making music is just one small part of their cultural imprint. Consider hip-hop’s early days when Adidas struck a $1 million deal with Run-DMC after the group performed the song “My Adidas” — it’s considered to be rap’s first endorsement deal — or Sean Combs’ savvy move from music to apparel with the 1998 launch of his label Sean John or Kendrick Lamar’s collaboration with Nike. Others including Karl Kani, Carl Jones of Cross Colours and the team behind FUBU (led by “Shark Tank” judge Daymond John) have made clothes expressly designed for hip-hop audiences.

Viewed cynically, it’s an artist selling out, but in the hip-hop community, where “making it” has long been the goal for many artists, these hangups don’t exist. (As Jay-Z once rapped, “I’m not a businessman / I’m a business, man.”) Few would deny there’s almost nothing more American than financially capitalizing on a moment.

As for the luxury industry, it would be remiss to not capitalize on hip-hop’s built-in cultural cachet, especially when brands such as Christian Louboutin and Givenchy are often name-dropped in songs. But it should take care, as Henson says, to not exploit it. “There is often outrage and disgust,” the stylist says when fashion refers to hip-hop in “a stereotypical way.”

“When people are speaking out about cultural appropriation it is because fashion has a huge platform,” says Henson, “and it forces people to live through that interpretation which is to say the least, difficult and exhausting.”

Henson adds that he recognizes the dual-sided nature of hip-hop’s commercial ascent, which brands are flocking toward. “Brands are changing their messaging. They are starting to include people of color, and more minorities because the minority dollar is strong,” the stylist says. “That has a good side and a bad side. It can be predatory, but there is a little bit of a leveling of the playing field and that has to do with hip-hop artists and their power and influence and what their voices can do.”

To be involved with the hip-hop community is to participate in the defining mood of the zeitgeist. Luckily, fashion and hip-hop aren’t stagnant ideas. They’re constantly in flux, evolving in ways bold and barely perceptible — but always aiming to be in line with that ineffable quality of being cool.

“You can’t really put your finger on it, but you know what hip-hop is when you hear it,” Romero says. “That’s a good way to describe hip-hop style. You can’t pigeonhole it anymore. It wasn’t meant to be that. What was once considered different is now everyday. And hopefully that is a reflection of society.”

For fashion news, follow us at @latimesimage on Twitter.

ALSO

Read the series: The Age of Hip-Hop — from the streets to cultural dominance

Hip-hop’s breakthrough fashion players

Five sonic leaps that changed the sound of hip-hop

Why hip-hop, once ostracized in clubs, is ruling the festival circuit

Pharrell and Chad Hugo redefined hip-hop's sound, now they've put out a N.E.R.D response to Trump

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.