Book review: ‘The Tragedy of Arthur’ by Arthur Phillips

- Share via

The Tragedy of Arthur

A Novel

Arthur Phillips

Random House: 368 pp., $26

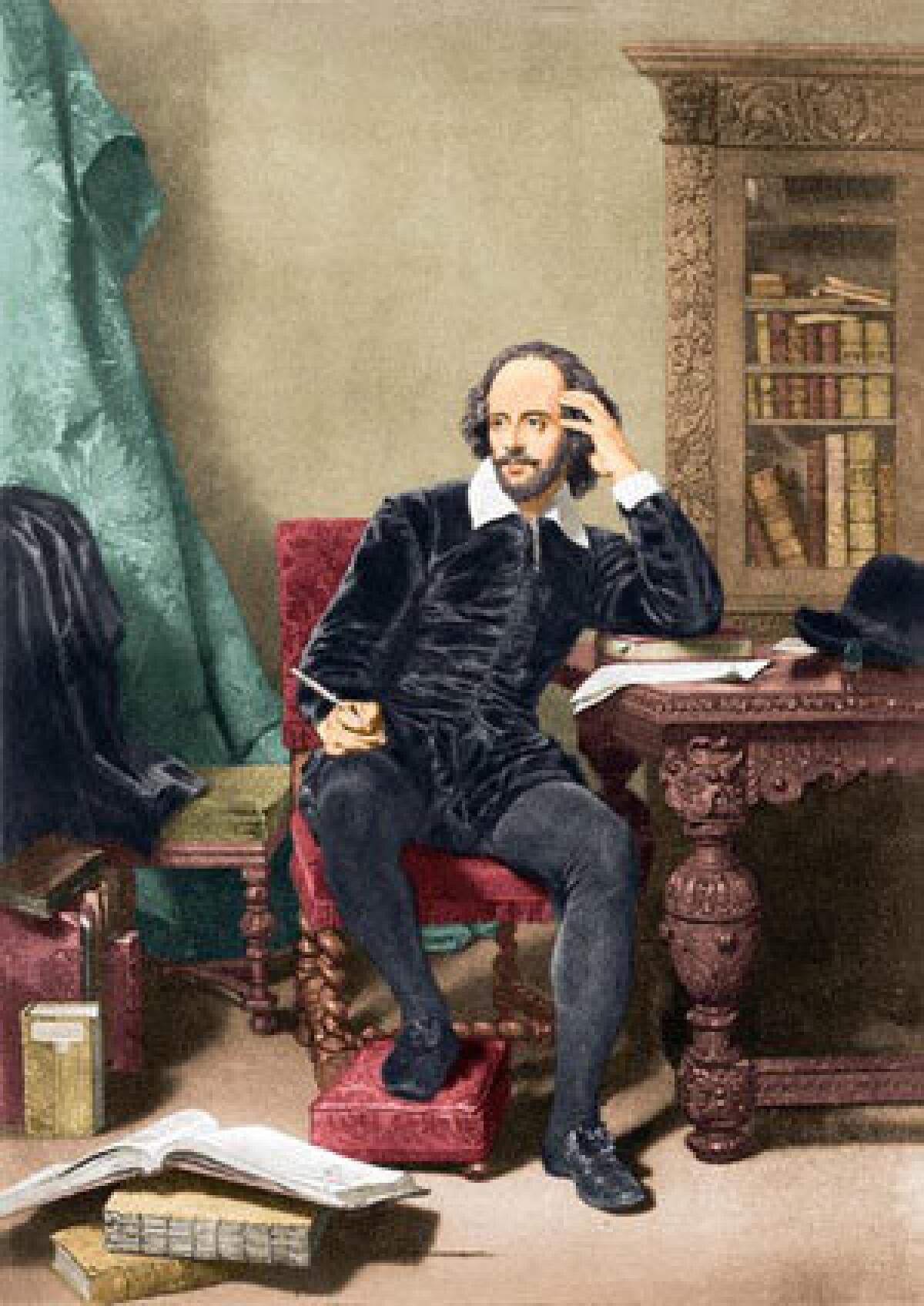

First, the MacGuffin: Arthur Phillips’ fifth novel, “The Tragedy of Arthur,” is built around a full-length, five-act Shakespeare play, “The Most Excellent and Tragical Historie of Arthur, King of Britain,” composed (or, in the conceit of the novel, “discovered”) by Phillips himself. It’s a bravura strategy, relying on his ability to inhabit the rhythms, “the feeling of Shakespeare … it’s like a fingerprint.” Although I’m not much of a Shakespearean, I’d say Phillips pulls it off. But the real triumph of this dizzyingly self-reflective novel is that it doesn’t matter that the Shakespeare (faux or actual) is almost entirely beside the point. What’s essential, rather, is the saga that surrounds it, a family drama involving (yes) Arthur Phillips, who both is and isn’t the author of this book.

Phillips, of course, has traveled down this road before. His 2004 novel “The Egyptologist” also involves found writing — in that book’s case, the erotic poems of a forgotten pharaoh — and the commentary of an unreliable narrator. It’s a conceit lifted from Vladimir Nabokov’s 1962 novel “Pale Fire,” whose spirit inhabits both “The Egyptologist” and “The Tragedy of Arthur,” but here, Phillips takes the concept one step further by connecting it to his identity.

There’s an elusive fluidity to the setup; the Arthur Phillips of the book is, like his creator, the author of four previous novels, born in Minneapolis and educated at Harvard, a writer whose work plays at the edges of the believable and is more concerned with what we might accept than what we know. Still, like “Pale Fire’s” Charles Kinbote, this Phillips is also a shade, a chimera, a man with a twin sister (that favorite Shakespearean device) and a forger father imprisoned for one failed scam after another.

We learn this in the extended introduction that forms the backbone of the book: It gives us Phillips’ story of how he came to possess the play, his back-and-forth over its authenticity, his ruminations on family and fiction, on the falsity of memoir and how the people closest to us let us down. “[M]y father,” he writes early in the novel, “… was extolling the greatness of anyone who adds to the world’s store of wonder and magic, disorder, confusion, possibility, ‘the wizards.’ If he had been trying to hypnotize me for life ahead, it wouldn’t have been much different.”

What he’s evoking are the roots of his literary imagination, which is itself a response to “the world’s vanishing faith in wonder,” much as the father claims his own exploits to be. And yet, who is this father? How real is he? And what does it mean if he never actually existed, in this form anyway? These questions are delirious, infectious, and as “The Tragedy of Arthur” progresses, we begin to understand that not only are they at the heart of Phillips’ narrative, but so is the confusion (or better yet: derangement) they provoke.

The reason all this works is that Phillips never breaks character, never lets on that the whole book is an elaborate put-on. Slowly, across 256 pages (the length of the introduction; the play itself comes in at a tidy 106), he develops the con, stringing us along with allusions and anecdotes and always, always implicating himself. “Like most good pigeons, I took on most of the work of conning me myself,” he writes after a prison visit in which his father reveals the existence of something, he won’t say what, that he wants to share.

The item in question, it turns out, is “a quarto edition, dated 1597” of the play “The Tragedy of Arthur”: a work unrecorded, unremarked on, never before known to exist. To make this credible, Phillips offers a good deal of background, and among the pleasures of “The Tragedy of Arthur” is its crash course in Shakespearean scholarship, the arguments over disputed plays such as “Edward III” or “The Two Noble Kinsmen,” the fate of lost works such as “Cardenio” and “Love’s Labour’s Won.”

All protestations to the contrary — “I have never much liked Shakespeare,” the book begins, “I find the plays more pleasant to read than to watch, but I could do without him, up to and including this unstoppable and unfortunate book” — Phillips clearly has an affinity for the playwright, and the novel works with classic tropes. There’s a dark lady and some conjecture about who wrote the plays; there are romantic complications in which the twins are involved. There are odd coincidences and curiosities; in the novel, as in real life, Phillips and Shakespeare share a birthday, April 23.

Most important, there are questions about heritage and legacy, and who is fit to wear the crown. When, at the end of the play’s first act, young King Arthur declares, “I bear his blood, his wit, his faults, his sin, / Save he did crave a kingdom for his own, / While crown unsought now perches up on me. / This glistering ring was plucked o’ my father’s / corpse,” he is speaking not just for Shakespeare’s reluctant heirs and kings (Prince Hal, Hamlet), but also for the character of Phillips himself.

Eventually, the narrator becomes convinced that the play is just another forgery, but there’s nothing he can do to make it right. This is a metaphor for fate and family, which bind Phillips as tightly as they do Arthur, or any character in Shakespeare’s work. Yet, Phillips suggests, none of that may make a difference if we allow ourselves to be ennobled, rather than diminished, by circumstance. As he reflects of Shakespeare: “(A) We judge him the best. (B) He has survived all this time. But, really, what if it’s the other way around?”

The implication is that he’s just a writer, one who worked out of a combination of necessity and opportunity, not unlike Phillips himself. “He deserves only what you deserve,” Phillips’ twin argues: “To be read and treated like a writer … not to be punished with this religion of his perfection and prophecy.” The same, this deft, delightful novel argues, is true of all of us, in literature as in life.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.