Book Review: ‘The President and the Assassin’ by Scott Miller

- Share via

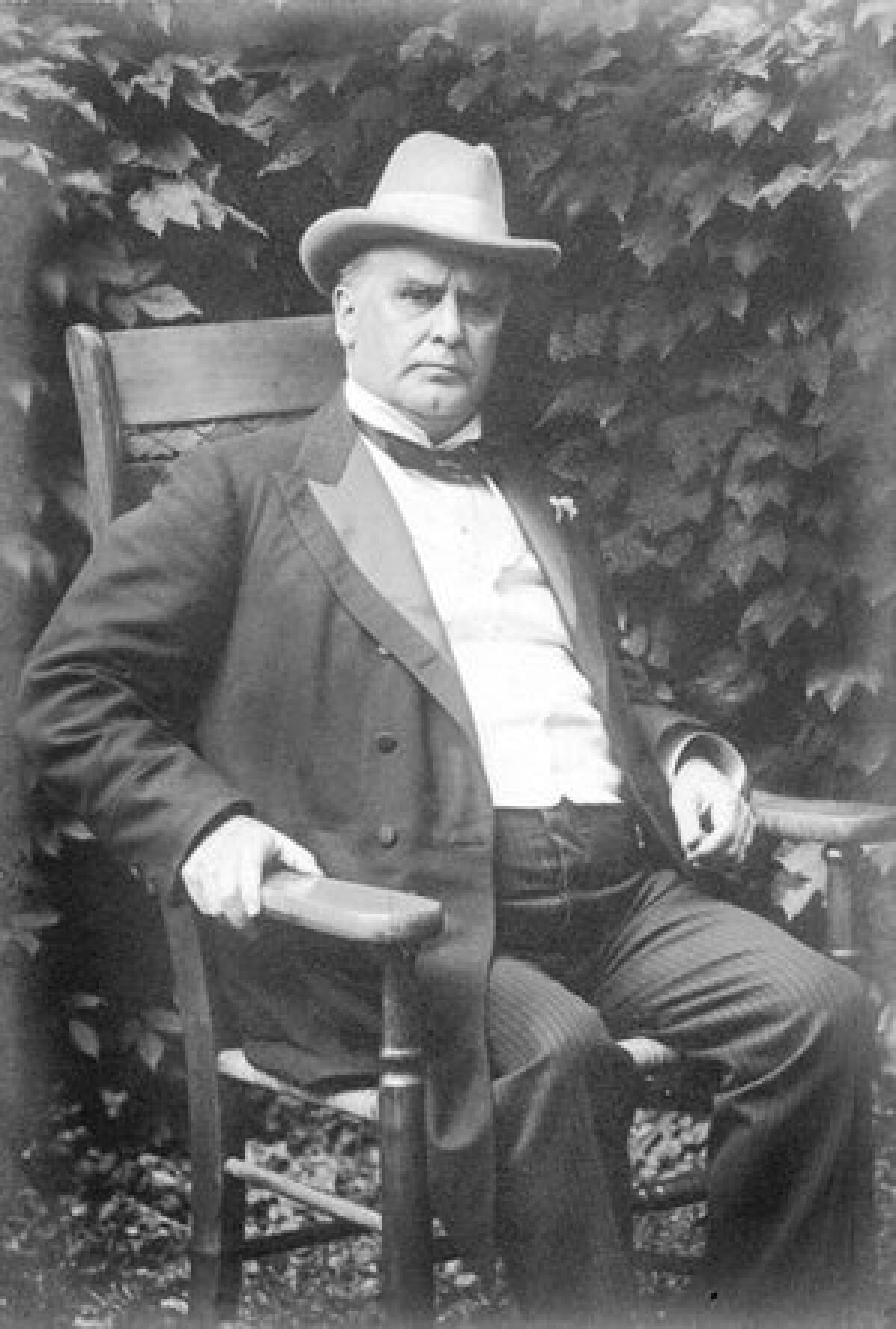

The President and the Assassin: McKinley, Terror, and Empire at the Dawn of the American Century

Scott Miller

Random House: 432 pp., $28

Veteran journalist Scott Miller has done something very interesting in his first book: He has conjoined two kinds of histories to create a portrait of the United States at the turn of the 20th century as a country divided between worldviews so radically dissimilar that they hardly seemed to be describing the same reality. Was America a booming nation whose rapidly growing industries were creating wealth on an unprecedented scale? Or was it a place of misery for working people who labored in horrific conditions that would never voluntarily be improved by the capitalist class and the politicians who served it? It was both, and Miller’s narrative whipsaws between those realities as it chronicles the years leading to President William McKinley’s assassination in 1901 by self-proclaimed anarchist Leon Czolgosz.

Decried by anarchists as a stooge of the plutocrats, McKinley was a well-loved public figure noted for his easy affability with the common man and woman. They were well-served, this staunch Republican believed, by his support of business interests: “Industry was America … it drove innovation and improved standards of living.” That notion eventually led him to embrace military adventures abroad, even though early in his presidency he described the forcible annexation of foreign territories as “criminal aggression.” But American industries produced more goods than Americans could buy, and a regular cycle of overproduction followed by financial panics roiled the economy throughout the late 19th century.

The solution, McKinley came to believe after he took office in 1897, was overseas markets for American products. He didn’t want to impose political rule on restive native populations, as Spain did in its colonies. He wanted, in Miller’s summary, “reliable and protected trading routes — as well as political and economic stability within America’s trading partners.” The difference for the locals would be minimal, as Cuban and Philippine rebels learned after throwing their support to American troops they believed were liberating them, only to hear all talk of self-government relegated to the unspecified future after the U.S. victory in the Spanish-American War. Perhaps they took comfort from McKinley’s assurances that “their welfare is our welfare.”

Czolgosz had every reason to disagree with that assessment. He had bitter personal experience with the consequences of unfettered capitalism. The son of Polish immigrants, he went to work at age 10. The Panic of 1893 led the Cleveland Rolling Mill Co. to impose draconian wage cuts that provoked a strike; Czolgosz was among the workers blacklisted for walking off the job. He was “quiet and not so happy” after that, his brother remarked. Rejecting the devout Catholicism of his childhood, Czolgosz found a new religion in anarchism, which asserted that only through violent action could workers break the capitalists stranglehold on power. At this point, Miller leaves Czolgosz on the sidelines as he backtracks to trace the growth of anarchism from the 1870s through the 1890s, spending a good deal of time on the movement’s key figures in the U.S.: Albert Parsons, Johann Most and Emma Goldman. Alternating chapters follow the progress of the Spanish-American War and McKinley’s evolving attitude toward imperialism.

There are difficulties with this back-and-forth technique. Casual readers may have trouble keeping track of the dual story lines, and Czolgosz’s reemergence after a 150-page absence from the text is jarring. Students of labor history will be familiar with the parade of militant actions: the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, the execution of Parsons and three other anarchist leaders after an 1886 demonstration that ended with violence in Chicago’s Haymarket Square, the Homestead Steel strike of 1892 and anarchist Alexander Berkman’s attempt to assassinate the man responsible for crushing it. Aficionados of more traditional history will be equally familiar with the events of the Spanish-American War, including the sinking of the Maine and George Dewey’s destruction of the Spanish fleet at Manila as well as the U.S. annexation of Cuba and the Philippines.

Specialists will find little that’s new here, and generalists may be frustrated by Miller’s approach. Yet there’s great value in this two-pronged attack, which climaxes with McKinley’s assassination and the repression of anarchists that followed. Although Czolgosz had an exceedingly tenuous connection to anarchism as a movement, Goldman and Most were both jailed for inciting his act through their speeches and writings, and in 1903 Congress passed an act banning anarchists from entering the U.S. Miller’s parallel stories raise thorny issues that continue to plague us.

The author doesn’t emphasize his book’s contemporary resonances, but he doesn’t need to. They’re evident when he summarizes public support for the roundup of anarchists: “This … was no time for civil liberties. The very fabric of their society was at risk.” Miller’s depiction of national liberation movements supported only when they served the United States’ commercial and strategic interests doesn’t seem outdated as we consider our government’s various responses to the ongoing uprisings in the Middle East. The argument that business works best when left to its own unregulated devices has not gone out of fashion. Terrorism remains the weapon of the furious and powerless. Matter-of-factly laying out the opinions and actions of capitalist and anarchist alike, casting an unflinching eye on the brutal excesses of which both were capable, Miller suggests that it’s dangerous to be oblivious to other people’s points of view, and that parallel worlds can collide with disastrous consequences.

Smith is a contributing editor for the American Scholar and reviews books for The Times, the Washington Post and the Chicago Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.