‘All That Follows: A Novel’ by Jim Crace

- Share via

All That Follows

A Novel

Jim Crace

Nan A. Talese / Doubleday: 230 pp., $25.95

British novelist Jim Crace has written in “Gift of Stones” about a Stone Age community that senses its doom when a Bronze Age tribe settles nearby. He has written in “Quarantine” of a young and annoying Jesus spending his 40 desert days among craggy cave-dwelling neighbors. In “Being Dead” he has written of the life in and around the decaying bodies of a murdered husband and wife.

In an odd way, each of those novels is a masterpiece. Not for the extremity of their stories, entirely removed from any ordinary notion of literary realism, but for their astonishing emotional realism.

Nothing human is alien to me, the Latin saying goes; with Crace, whose best is unsurpassed by any living British writer, nothing alien is not human. Poet Marianne Moore wrote of imaginary gardens with real tigers in them; Crace’s wildly imaginary gardens are populated not by tigers but by real human spirits.

With “All That Follows,” he has tried his hand at a small, essentially realistic novel; one set a few years in a future that is only a slightly intensified present. There is quite a lot to like in it, but it doesn’t really suit him. Lifted like Antaeus from his own ground, or perhaps an Ariel obliged to walk, he loses much of his strength.

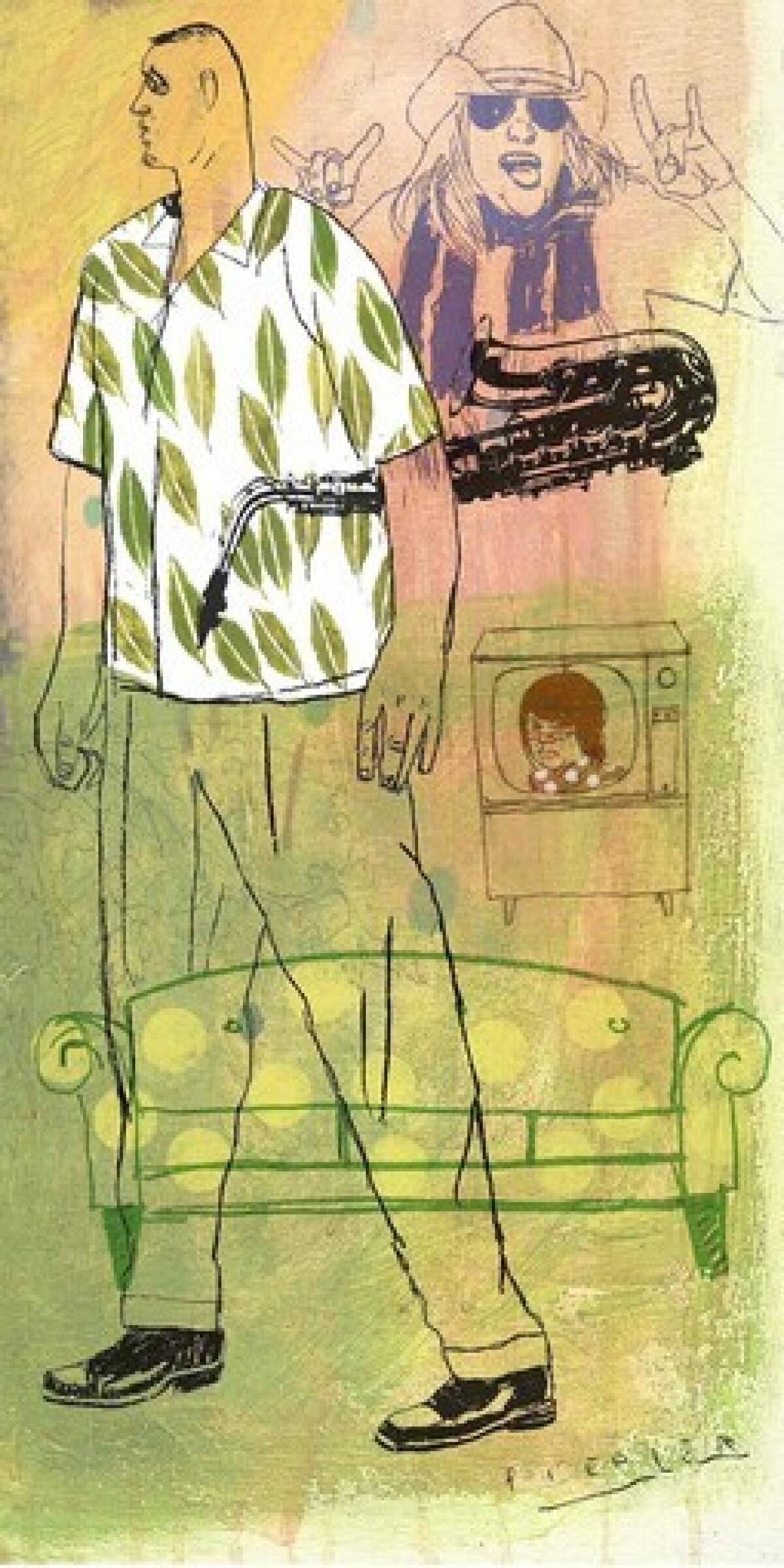

Leonard Lessing, the novel’s protagonist, is a jazz saxophonist who at 50 and with the excuse of a shoulder injury has temporarily retired from an admired career.

He has retired from much more -- essentially from any action or decision involving effort or courage.

He spends much of his day as a couch potato, watching the news and aimlessly Googling, while waiting on his wife, Francine, with a nervous assiduity that seeks to mask his depressed passiveness. If he fails at his early morning routine of getting her breakfast, “then he will steep like unattended tea, growing darker by the moment.”

Hostages and a plan

Francine, a busy teacher, has been unhappy since quarreling and losing touch with a grown daughter. She is sparky by nature, though, and Leonard’s mix of supineness and cosseting makes things worse. They’d first met when she approached him after he’d played a wild jazz solo. “Truly valiant,” she’d said; what followed were adventurous years of gigs and political demonstrations. “What I couldn’t guess back then,” she tells him now, “was that the jazz was the only thing that wasn’t . . . decaf.”

Leonard’s funk begins to abate when he watches a news report about a radical group taking hostages in a nearby town. He recognizes the leader from a trip he’d made to Texas in 2006, 18 years earlier. He’d gone there hoping to link up with Nadia, once a would-be girlfriend. Instead he found her living with Maxie, a blowhard who was trying to organize a violent outbreak during a book talk by Laura Bush. Leonard reluctantly agreed to participate, chickened out, and it all went ludicrously wrong. Crace is excellent at human ludicrousness; it’s only little removed from human tragedy.

Now, vaguely stirred, Leonard drives to the hostage house, besieged by security and a host of ravenous journalists. When a teenage girl comes up to announce she is Maxie’s and Nadia’s daughter Lucy, Leonard approaches her. And there he begins a series of ventures and retreats that will end up edging him out of his anomie.

The ups and downs are intricate. Lucy proposes to disappear, announce her own kidnapping and threaten that she will be killed unless the hostages are released. Touchingly, she expects Maxie to be more father than terrorist. Leonard agrees to help, then retreats, then reengages.

Meanwhile, Francine finds her spirits rekindled by his fumbling ventures into real action, however farfetched. It is his lost wildness she missed.

Crace does well configuring Leonard’s rabbit state, Francine’s tormented urgency and Lucy’s appealing teenage farfetchedness. But he is unable to provide a convincing story for them to move through; it is thinly and hastily contrived. At home as he is in the towers and spires of his fable-like fiction, realism’s daily housekeeping, with its narrative chores and due bills, evades him.

Story in music

The writing, though it has its moments, seems to struggle as well. Only in passages evoking the lost wildness of Leonard’s saxophone improvising does it achieve the visionary immediacy of Crace’s distinctive strength.

“He’s on the tightrope, balancing. It’s technique and abandonment. He is elated, yes, but he is also terrified.” And, Crace continues: “He has exhaustively prepared in order to seem daringly unprepared. But here, tonight, he is not playing what he hears; he is hearing what he plays.”

Eder, a former Times book critic, was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for criticism in 1987.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.