Critic’s Notebook: Ernie Kovacs and ‘H.R. Pufnstuf’ added surreal twist to TV

- Share via

At any given time, most things on television resemble other things on television, sharing narrative conventions and visual conceptions, techniques and technologies, even ways of treating and reflecting their audience. But there are always a few black sheep about, horses of a different color – artists who work against the system even as they operate within it and out of whatever combination of intention or helplessness create their own unaccountable realities.

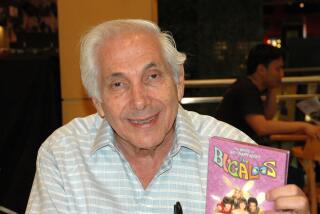

Two such other worlds get box-set video releases this month: “The Ernie Kovacs Collection” (Shout Factory, due April 19), a well-chosen, six-disc overview of what survives of Kovacs’ TV career, from his early ‘50s NBC morning show to his early ‘60s ABC specials, and “H.R. Pufnstuf: The Complete Series” (Vivendi, April 12), Sid and Marty Krofft’s dawn-of-the-’70s Saturday-morning musical-fantasy sitcom about a boy, a witch and a dragon.

Even in his short lifetime — he was killed in an automobile accident in 1962, days before his 43rd birthday — Kovacs was hailed as a mad genius and poet of the small screen, and as such he was both celebrated and marginal: never really successful but never out of work for long. He had shows on every network, in every hour. As their star, writer, producer and eventually co-director, he was as much an auteur as TV has produced and possibly the first person in television to really explore it — not to make fun of what TV showed, which he also did — but to mess with the medium itself, to pick it apart and reassemble it inside out, with the tubes and wires showing. He was a video artist before artists got around to making video — it is not a far leap from late Kovacs, with its deadpan visual punning, to Bruce Nauman or William Wegman.

He worked in many modes. Early on, there are skits and comic monologues and puppets. As he develops, verbal comedy gives way to visual, until he’s making shows with no talk at all. Water bursts through a painting of a dam. A light drawn on a wall shines real light. A giggling Mona Lisa is revealed to have a body extending beneath the frame, whose toes are being licked by a cat; household objects are orchestrated like dancers, dancers in gorilla suits perform “Swan Lake.”

Unlike other early TV stars, Kovacs’ background was not in nightclubs or vaudeville but in radio and theater; he started in television just as it was being improvised into being, and his delivery was keyed not to the crowd but to the intimacy of the soundstage. Kovacs lived large — “Nothing in Moderation” is inscribed on his headstone — but on-screen he was a quiet force, centered and unhurried. He preferred to work without an audience and disdained the laugh track, which gives his later work, filled with pauses and silences and long stares, a kind of suspended, floating, foreign quality. Though Kovacs often addresses his viewers, one feels they are just icing on his cake. During one routine, wife and frequent co-star Edie Adams turns to the camera to say, “Mr. Kovacs and I are married in real life; he does many funny things like this around the house and occasionally talks the networks into letting him do it in public.”

While only a small fraction of Kovacs’ work survives, all 17 episodes of “H.R. Pufnstuf” are gathered in its new box set. This is just about right, as much juice having been wrung from these basic characters and secondhand situations as anyone could reasonably expect. I mean no disrespect: If the scripts seem to have been jotted on cocktail napkins over lunch, to bring them to life took time and care and effort. It’s this mix of modes that gives the series its charm. It is ridiculous and, in its way, beautiful — a show a child could easily imagine but never make.

Jack Wild, who had been the Artful Dodger in the movie “Oliver!,” stars as Jimmy, of whom there is nothing to say past that he is good and has a talking flute coveted by Witchiepoo (an energetic Billie Hayes, channeling Margaret Hamilton and Marjorie Main). Jimmy’s protector is the eponymous Pufnstuf, the mayor of Living Island, a green and orange dragon with a football of a head and an accent straight out of Mayberry.

Lifted largely from “The Wizard Oz” (transported young person, harried by witch, befriended by talking animals and objects, seeks return home) with a touch of “The Tempest” (shipwreck, magical island, supernatural authority figure living in a cave), the narrative is mostly a convenience for the transmission of light and music and manic activity. Like Kovacs, the Kroffts overspent to get the effects they wanted, and though the sets are largely painted flats, they are also in their way enchanting. As with that other, similarly named dragon, the Puff of song, “Pufnstuf” has been hopefully claimed as a drug reference — “Puffin’ stuff,” tee hee — and while that is likely not so, it is a fact that the characters often do end up drugged and that the whole milieu describes a sort of kiddie psychedelia. Crazy, but cool.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.