Fiction Shelf

- Share via

Innocence

A Novel

Louis B. Jones

Counterpoint: 160 pp., $14.95 paper

The plot of Louis B. Jones’ new novel seems to promise an antic, postmodern free-for-all: A middle-aged former Episcopalian priest, now employed in Marin County real estate, takes a weekend tour of Sonoma wine country with his new girlfriend. Both have recently undergone surgeries to repair a cleft palate, both are sexually inexperienced, and both are grappling with issues of self-definition and identity.

In short order, they find themselves stranded on a country estate in the company of seven developmentally disabled adults, one of whom is pregnant and requires an emergency C-section.

Despite this over-the-top setup, Jones’ novel is a philosophical, even quiet book, in which the unusual events are presented without metaphorical quotation marks. The characters’ various shortcomings and disabilities are used not playfully or as set dressing but as beautiful, if gently funny, examples of human nature.

John Gegenuber, the narrator and aforementioned ex-priest, remains deeply real despite the chaotic world Jones has placed him in. His disquisitions on real estate, religion and pornography have the surprising effect of giving the seemingly maximalist situations in “Innocence” great depth.

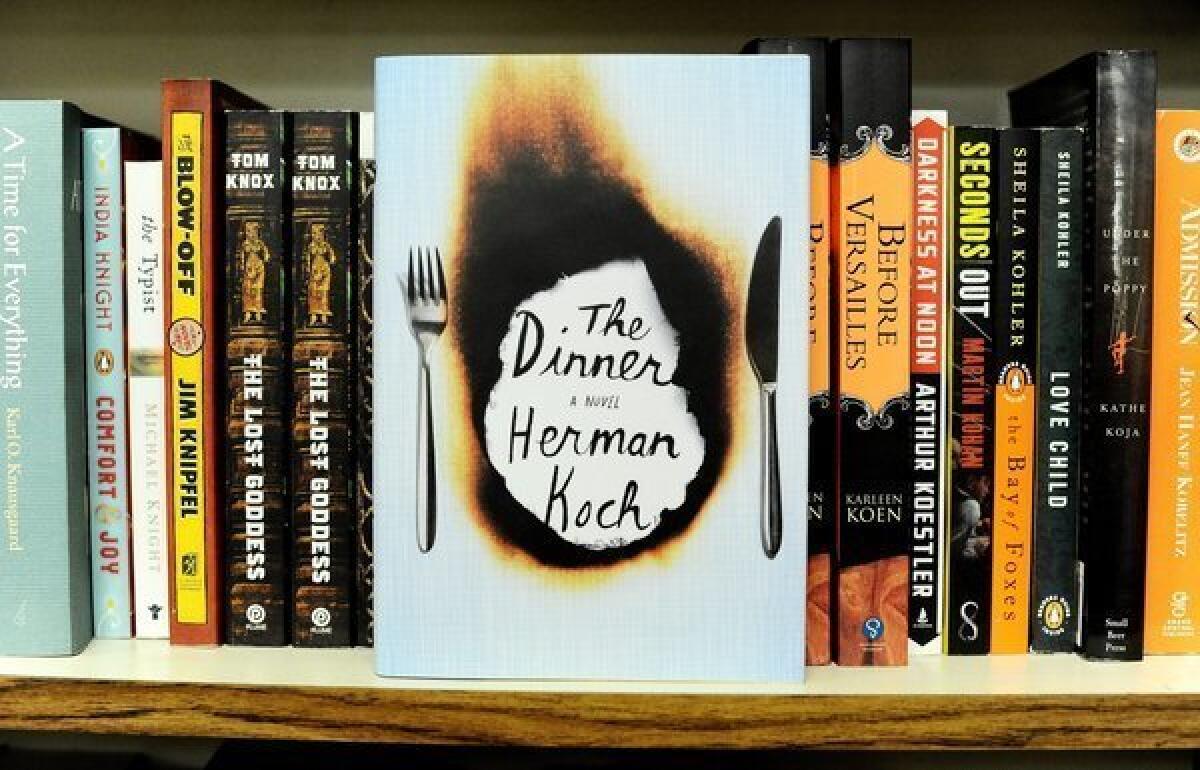

The Dinner

A Novel

Herman Koch

Hogarth Press: 304 pp., $24

Two couples meet for dinner at a fancy restaurant in Holland. They have arranged this meal to discuss their sons, but conversation strays to other topics — menopause, for instance, and Woody Allen.

Narrator Paul Lohman is smart and appealingly snarky, a family man and one-time history teacher. The other guests are Paul’s wife, sister-in-law and brother Serge, the latter a smarmy, glad-handing politician who’s a shoo-in as the next prime minister.

Paul is an astute observer and analyst, quick to point out the failings of others and to parse the travails of modern bourgeois life, like shaving: “If you don’t scrape off the day’s stubble, you were too lazy to shave; two days’ beard immediately makes them wonder if this is some new look; three days or more is just a step from total dissolution…No matter what you do, you’re not free. Shaving is a statement as well.”

But the urbane, intelligent flatness of the Lohmans’ European liberalism soon reveals itself as a smoke screen. The sons have been involved in something so disturbing it would be better that readers discover it on their own; nor are the parents as blameless as they seem.

The real pleasure of “The Dinner” lies in its ability to slowly gain your trust as the meal progresses — from aperitifs, to hors d’oeuvres, to the entrée’s shocking main fare — so by the time the dessert menu comes around you are unable to refuse one more bite.

Life Form

Amelie Nothomb, translated by Alison Anderson

Europa Editions: 144 pp., $15 paper

“Life Form,” an epistolary novel by the prolific Belgian author Amelie Nothomb, begins as the prolific Belgian author Amelie Nothomb receives “a new sort of letter” in the mail.

The letter is from Melvin Mapple, an American soldier stationed in Iraq who reveals that he is one of a group of soldiers suffering from wartime obesity; at 400 pounds and growing, he can barely squeeze into his XXXXL uniform. Melvin says he has named his extra fat “Scheherazade,” and considers her something between lover, victim and friend.

As Amelie and Melvin continue their correspondence, Nothomb ponders the act of letter writing, “a form of writing devoted to another person.” She shares aspects of her creative process with Melvin and encourages him to view his weight gain as an artistic act. Through their correspondence, the two construct a separate, shared reality in text — one that may or may not be true to life.

Translated by Alison Anderson, Nothomb’s prose has a hard-edged clarity and a slyness to it. References to newspaper articles, books and true current events give “Life Form” — tinged with strangeness as it is — a realism that makes the book’s ending that much more of a delightful surprise.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.