‘The House I Lived In’

- Share via

The man showing you around the house, and he’s perfectly nice but you wish he’d just leave. You’ve come here to commune with the owner of the house and it’s a communion for two—three’s a crowd. You’ve got just 24 hours, a mere 1,440 minutes, and every minute spent with this man, this property manager, is a minute wasted. Now he’s leading you into the kitchen, pointing out the microwave.

Microwave? Is he serious?

Finally he hands you the keys and says he’ll be back this time tomorrow. “Enjoy,” he says, and you watch him drive away, the big electric gate closing slowly behind him, and all at once it’s still and silent in the house, except for the voice of Frank Sinatra. Not the Sinatra piped into every room via the hidden master stereo, which the property manager has switched on for your benefit, but the real Sinatra: You hear the haunting echo of his speaking voice, because this was Sinatra’s house, his home, and for one shining “night and day,” you’re the guest of his ghost.

Twin Palms, the four-bedroom, 4,500-square-foot mini-mansion where Sinatra lived from 1947 until about 1954, sits plainly and unassumingly a mile from busy downtown Palm Springs, right off one of the city’s main drags. Back when Palm Springs was a drowsy desert village, Sinatra commissioned the house to be built as the primary residence for his family, and he wanted it built fast. Workers using floodlights labored around the clock.

But not long after moving day, Sinatra had a change of heart. A sea change. He met Ava Gardner, the love of his life, and promptly left his wife Nancy, who begrudgingly granted him a divorce. Twin Palms soon became the setting for one of the 20th century’s great romances, the amphitheater in which Sinatra and Gardner conducted their operatic affair. “Maybe it’s the air, maybe it’s the altitude, maybe it’s just the place’s goddamn karma,” Gardner wrote in her 1990 autobiography, “but Frank’s establishment in Palm Springs, the only house we really could ever call our own, has seen some pretty amazing occurrences.”

Amazing was Gardner’s catchall word for the intense violence and passion that defined her off-and-on saga with Sinatra. After half a dozen tumultuous years, the two were finally forced to conclude that they couldn’t live together. Sinatra sold Twin Palms and bought a bigger place on the other side of town, which came to be known as The Compound. Twin Palms changed hands several times in the next five decades, and eventually fell into disrepair, its roof caving in. Recently, however, the house underwent a full and careful restoration, and today Twin Palms belongs to three New Yorkers who gladly rent it to the curious and the Sinatra-besotted for $2,150 a night in season.

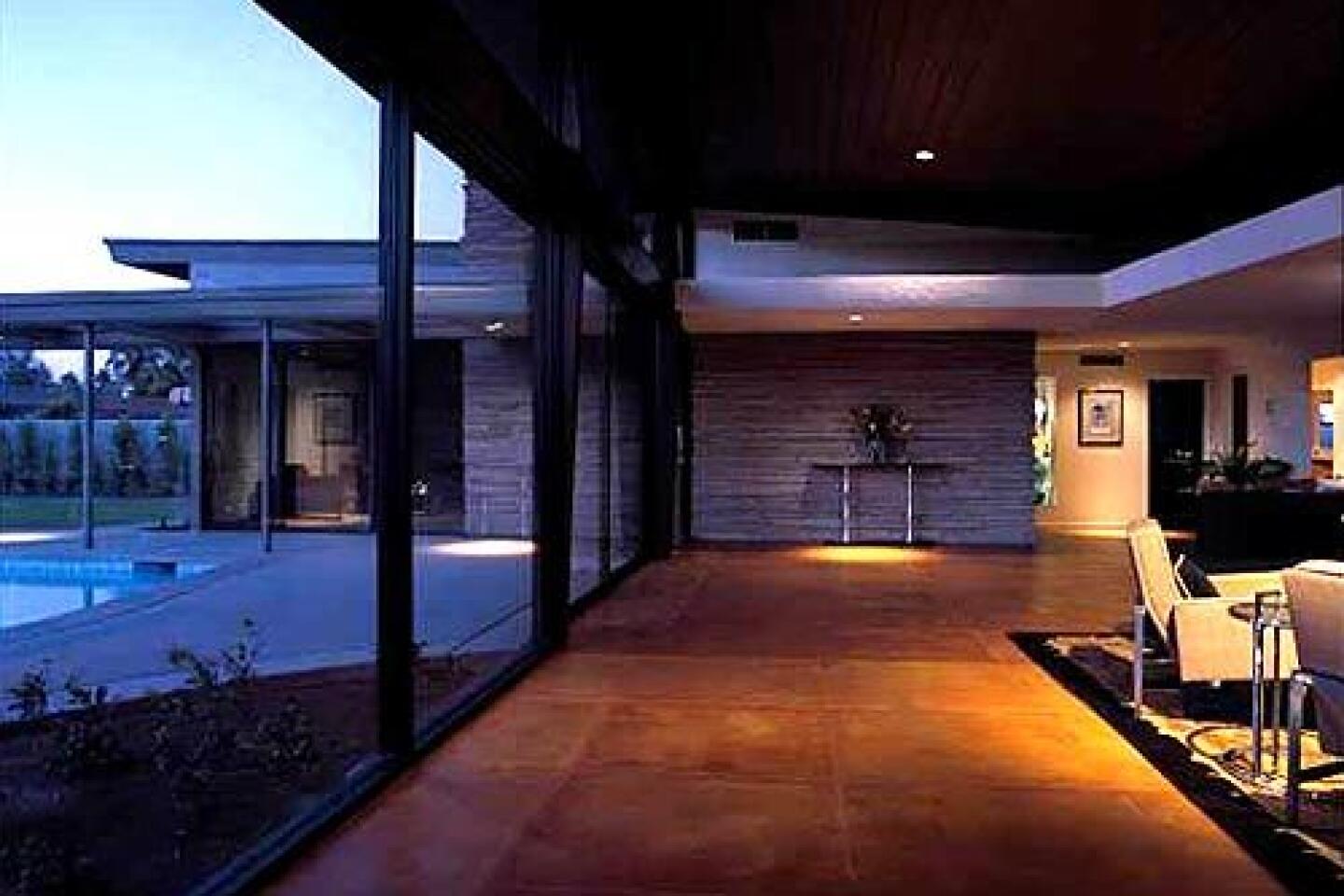

DESPITE ITS SIZE, THE HOUSE IS COZY, AND cheery, its rooms glittering with direct sunlight and fluttering with the reflected light off the pool. In fact, every window looks onto the pool, the sliding glass wall leads out to the pool, the house bends around the pool, and you quickly understand that the pool was the architect’s focus, the turquoise nexus around which Twin Palms was meant to revolve. Shaped like a piano and heated in the winter to 90 degrees, the pool is where Sinatra liked to hang, drink, talk, entertain, and where his legendary friends sometimes entertained him in unexpected ways. Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo staged a watery make-out session here one night.

So the first thing you do is sit by the pool. You ease into one of the low-slung chairs, close your eyes and lift your face to the winter sun. Sinatra sings “Oh! Look At Me Now,” while a few feet away, the two parallel palms for which the house was named sway in the breeze, their fronds making a soft shushing noise. Sinatra can’t be shushed, however. He’s in a full-throated roar. His voice comes toward you in gusts, and when you open your eyes you can’t say for sure what is causing the ripples on the pool’s surface, Sinatra or the breeze. All at once the music doesn’t seem to have a source, doesn’t seem piped into the rooms, but seems to wander from room to room of its own accord. The music makes Sinatra’s absence feel temporary, momentary, as if he’s just stepped out, run to the corner for another bottle of Jack, but he’ll be back any second, and when he comes through the door he’ll see you and growl: “What the hell are you doing in my house? Where’s Ava?”

An hour passes. The sun wafts downward like a feather on the wind. The temperature dips below 60 and you become aware of the first long shadows falling across the lawn. You put on a sweater and check your watch. Just 21 hours left.

The furniture in the house is vintage, but other than some ancient recording equipment in the garage, not a stick of it is Sinatra’s. It’s all some interior decorator’s idea of Sinatra’s taste. But who cares? They can change the furniture all they want—they can’t change the view between the palm trees. This is his view. You’re oriented as he was. You revel in the feng shui of Frank. You stare along Sinatra’s sightlines and drift back, back, slipping into 1951 as if it were the terrycloth robe on the back of the bathroom door. You gaze at the mountain and imagine Sinatra gazing at the same mountain while planning another night at Chasen’s, or fretting about how to land that role in “From Here to Eternity,” while Ava hides inside her private bathroom (with the one-way peek-a-boo mirror on the door, so she could see who was lurking out there), and Bogey and Betty drop by, and the newspapers say Louis will go the distance against Marciano, but you’re not so sure . . . .

Suddenly you’re overwhelmed by the desire to tell someone where you are. You phone your friend Emily in Chicago. Guess where I am. Where? Frank Sinatra’s house. Really? Sitting by his pool—the same pool where Lana Turner went skinny-dipping! I hope they changed the water, Emily says. I hope they didn’t, you say.

You’re not comfortable with idolatry. You’ve never conceded any kinship with people who worship celebrities. You once visited Graceland and felt very distant from the throngs standing in line, waiting their turn to walk across Elvis’ shag rugs. You shuddered at the ghouls who logged onto EBay and bid for Britney Spears’ used chewing gum. But Sinatra is different, you tell yourself. Sinatra is—you know, Sinatra.

Of course it’s bunk. Sinatra is simply your idea of a celebrity worth worshipping. There is something about Sinatra that hits you where you live, and there always has been. Partly it’s the swagger, the look, the cool. He reminds you of the guys from the old neighborhood, the indomitable alphas you emulated growing up. Partly it’s his respect for words. He’s the consummate writer’s singer. “I’ve always believed that the written word is first, always first,” he once said of his art. “The word actually dictates to you in a song—it really tells you what it needs.” Partly it’s the fact that, at every turning point in your life, Sinatra’s sound was there, in the background, at your elbow, guiding you, goading you. But mostly it’s his voice, which carries some secret code that springs some hidden lock inside you. There is an alchemy about voices that can’t be explained or understood. Some speak to us, some don’t. You enjoy all kinds of voices. In your iPod at this moment are U2, Mary J. Blige, Death Cab for Cutie. And yet when the chips are down, when all seems lost, when your heart is aching or empty—or overfull—nothing will do but Sinatra. We hand over our hearts to those celebrities (or athletes, or painters, or physicists) who match our notion of the Ideal, and the choice is as personal, as chemical, and ultimately as involuntary as our choices of lovers and friends.

THE SUN IS SETTING. ALL THIS musing, all this music, has given you an appetite. You head into town. Your first stop is the cigar store (Sinatra on the store stereo, in an endless loop). Then the bookshop. You buy the recent Sinatra biography by Anthony Summers and Robbyn Swan, and a much-praised memoir by Sinatra’s assistant, George Jacobs. The property manager mentioned a ristorante owned by Sinatra’s former chef, Johnny Costa. You find it easily on the main drag. The waiter tries to hard-sell you on the pasta special, but you scan the menu and see something called Steak Sinatra—New York strip, sliced thick, sautèed in oil and garlic and mushrooms and bell peppers, then topped with a red wine sauce. Ring-a-ding-ding.

While waiting for dinner you read in Summers and Swan about Sinatra and Gardner getting arrested outside Palm Springs. “We shot up a few streetlights and store windows with the .38s, that’s all,” Frank said. “There was this one guy, we creased him a little bit across the stomach. But it’s nothing. Just a scratch.”

After dinner, while you’re having an espresso, the chef-owner pops out of the kitchen to say hello. Costa didn’t work at Twin Palms; he worked at The Compound. He tells you he liked Sinatra, enjoyed cooking for him, but boy oh boy the man had a temper. Pitched a fit one night at Villa Capri in Los Angeles. Threw a bottle across the room. Why? The waiters were hovering too close.

Costa asks about Twin Palms. Where is it again? Just down the road? He didn’t know. And he never imagined the house was available to be rented by any schmo off the street. He eyes you, suspicious—envious? You give him a whaddya-gonna-do shrug, then shove off, striding through the door with a certain swagger of your own.

Anyone needs me, I’ll be at Frank’s.

If you had a trench coat, you’d sling it over your shoulder.

Back at the house you resume your post by the pool and read more about Sinatra and Gardner. Loving each other. Leaving each other. The wild sex, the crazy jealousy, the suicide attempts, the screaming matches that brought Palm Springs PD to the house. You can almost see the lights of the patrol cars strobing the palms. (You’re tempted to phone an old girlfriend and start a raging fight, a real donnybrook. Mercifully the temptation passes.) It occurs to you that Sinatra and Gardner were like these two palms—side by side, inches apart, but always unsteady, always tilting away from each other, then lunging toward each other. You wonder if they noticed the metaphor. It’s hard to notice metaphors when you’re blotto.

You’ve read all these stories before, but being here makes them real. Tactile. One night, furious with Gardner, Sinatra broke a bottle of booze over the bathroom sink. The property manager told you this. You go inside and there it is, a long, jagged crack in the porcelain. You run your fingers over it. Whoever remodeled the house was wise enough to leave the original bathroom fixtures, with the old scars of love. You ask yourself: Are we most alive in those places where we are most in love? You’ve long suspected that this was so, but tonight is the first time you’ve felt the truth of it with your fingertips. And since Twin Palms is where Sinatra loved the most, it follows that this is the best place to know him, to commune with him. This is where Sinatra became Sinatra, the real Sinatra, not that mixed-up Mia Farrow Sinatra, or that crazy Tony Danza Sinatra, who consented to that cringe-making cameo on “Who’s the Boss?” This is where your Sinatra was born.

You see him walking into this house, that first time, in 1947, with noticeably less swagger, because everything was just starting to turn. A few years earlier he’d made tens of thousands of bobbysoxers swoon—now his popularity itself was swooning. His artistic obituary was being written by critics and columnists. Sinatra’s finished, they said. Washed up. A bum. He was on the verge of losing his voice, his hair, his nerve. But Twin Palms is where he would resurrect himself. From Twin Palms he launched one of the great comebacks in cultural history. He regained his voice, recorded his finest albums, reached out to Nelson Riddle, the arranger with whom he forged a beautifully simpatico partnership. He won that life-changing role in “From Here to Eternity” in 1953, took home the Oscar, and began to assemble his roundtable of night owls, the Rat Pack, who would supply the belly laughs he sorely needed. By the time he sold this house, in the mid-1950s, he was a new man. Brokenhearted, yes, but wiser, and ready to teach the rest of us about the lasting agonies of love, which are more than compensated for by the fleeting joys.

It’s a quarter to 3. Not really, but you can’t help hearing that song, because it’s late. You’re sleepy, and yet you don’t dare turn in because you have only 13 hours left. Maybe just a catnap, you tell yourself, curling up with your books. One last look out the bedroom window. Columns of steam swirling above the pool. Phantoms doing the Lindy.

I stand at your gate,

And the song that I sing is of moonlight . . .

You fall asleep, the pool like a warm blanket folded across the foot of the bed . . . your bed . . . Sinatra’s bed.

HOURS LATER YOU WAKE WITH a start. Dawn. You dive into the pool, swim laps until you can’t raise your arms. Breathing heavily you float on your back. Coffee—you must have coffee. You race into town, grab a cup of Starbucks and a sandwich, then hurry back to the house. Absorbed in your books, you lose track of time. The sun is soon overhead. You eat your sandwich. You turn up the stereo and stretch out, eyes closed, listening to the birds and the palm trees. One o’clock. Two o’clock. You never noticed how loud your wristwatch could be.

An hour left. You’re bargaining with time: Twenty-three hours ago you wanted to turn back the years; now you just want to slow down the seconds.

The property manager arrives, 20 minutes early. Early.

Party’s over, pal. You gather your things.

He asks how it was. Great, you tell him, hoarse. You hand him the keys. Does he notice that you hold them for an extra half second so that he has to yank them from your hand?

He asks idly if you’re heading back to Los Angeles.

Yes, you say, stifling a sigh, yes.

You’d planned to stop at Sinatra’s grave before leaving town, pay your respects, but you can’t. Sinatra’s grave is the last place you want to be right now. His grave would shatter this illusion that Sinatra is alive, very much alive, and of course it would dispel the twin illusion that you are Sinatra. It’s time to confess, to yourself if no one else, that you haven’t merely been communing with Sinatra, you’ve also been commandeering his identity. It wasn’t your plan when you came here, it just happened. Lying by his pool, sleeping in his bedroom, eating steak cooked by his chef, you journeyed deep into the Heart of Frankness, deeper than you expected, and you got lost, forgot yourself, until your personality forked. Now you must go back to the world, back to reality, back to yourself. A journey you view with deep foreboding. You’d rather walk back to Los Angeles in your socks.

The property manager doesn’t feel your foreboding. He can’t afford to care about your foreboding. He has other appointments, places to be, and so he leads you gently, kindly, to the door. Why are you suddenly reminded of the climactic scene in “Dead Man Walking”?

The maid arrives to clean the house. Lucky maid.

Moving more slowly than your grandfather ever did, you shuffle over to your rented Chevy Impala. It seemed a sexier car last night when you were leaving Johnny Costa’s, like something Sinatra would drive. Now it looks like an Edsel.

For the first time in your life you pray for a flat. No luck. Four good ones.

You hope the Chevy won’t start. You climb in. Turn the key. The engine revs. Damn reliable Chevys.

You slip it into drive and pull away. Slow. Slower.

Reluctantly you hit the gas. Ease into traffic. Only at the last possible second do you glance in the rearview and see what you have known was coming.

What you have been dreading these last 24 hours.

That big gate. Closing forever. Behind you.

J.R. Moehringer is a senior writer for West and the author of the memoir “The Tender Bar.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.