Vaccine against breast cancer, ovarian cancer promising in trial

- Share via

Monthly shots of a cancer vaccine produced encouraging results in a small, very early trial of 26 women with metastatic breast or ovarian cancer (cancer that has spread to other sites around the body), most of whom already had had three or more rounds of chemotherapy.

Among the 12 breast cancer patients, median survival time was 13.7 months and one patient was still alive at 37 months, when the paper was written up. Four remained stable during the course of the trial.

Among the 14 ovarian cancer patients, median survival was 15 months. One woman went 38 months before her disease progressed.

Side effects to the treatment were mild, mostly reactions at the injection site. (One patient developed anemia.)

Though the news -- which was published in the journal Clinical Cancer Research -- is encouraging, it’s also true that it’s a small, early pilot trial, and the paper didn’t have a control group nor discuss how long patients would be expected to live without such therapy. Drugs take a long time to get to the clinic. Before this drug would be approved, it would have to prove its salt in larger trials, and many don’t make it that far.

In most people’s minds, the word “vaccine” implies a shot you’d get before you ever had a disease to prevent its occurrence in the first place. Cancer vaccines like these – it’s an active area of research – are different. They work instead by ramping up immune responses to a cancer someone already has.

One might ask, if the immune system has the power to fight cancer cells, why doesn’t it just do it? After all, the cancer is already in the body, already presenting its foreign proteins to the immune cells. Can’t the immune system just go with that?

The issue is that for whatever reason, many of these bits of protein that are present on cancer cells only trigger a weak response, at best.

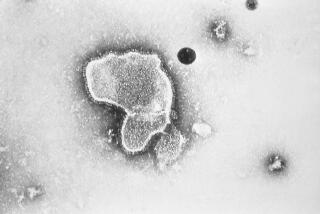

To get around that problem, the researchers genetically engineered a poxvirus so that once it got into cells it would produce two proteins often associated with tumor cells. The virus was also engineered to produce several other proteins that would stimulate T cells of the immune system to do a better job.

When delivered by a poxvirus this way, the proteins are presented to the immune system in a way that seems to elicit a better immune response. And once the immune system has learned to recognize these proteins, it will better attack tumor cells that make them when it encounters them.

In this trial, which was funded by and conducted at the National Cancer Institute, the benefit seemed strongest in those whose tumors were not as extensive and hadn’t had as much prior chemotherapy treatment. And other studies have suggested that when people’s diseases are really advanced and they’ve received lots of chemotherapy, their immune systems just can’t rally as well.

And so, the authors write in their report, “future cancer vaccine studies should … select patients with less aggressive tumors in the earlier stages of disease.” The scientists also say that the vaccine might work best when combined with other types of cancer therapies.

The research paper is posted here, but it costs $35 to see the whole thing. (You can read the abstract without paying, though.)

Read lots more about cancer vaccines at this site at the National Cancer Institute. It will tell you what kind of vaccine trials, for what kinds of cancer, are underway.

To read more health news, check out other items at the L.A. Times Booster Shots blog.