In Vietnamese American community, ‘communist’ still a hateful, and expensive, slur

- Share via

They were aging refugees from the Vietnam War, many of whom had endured arrest and imprisonment at the hands of the communist government before escaping to the United States.

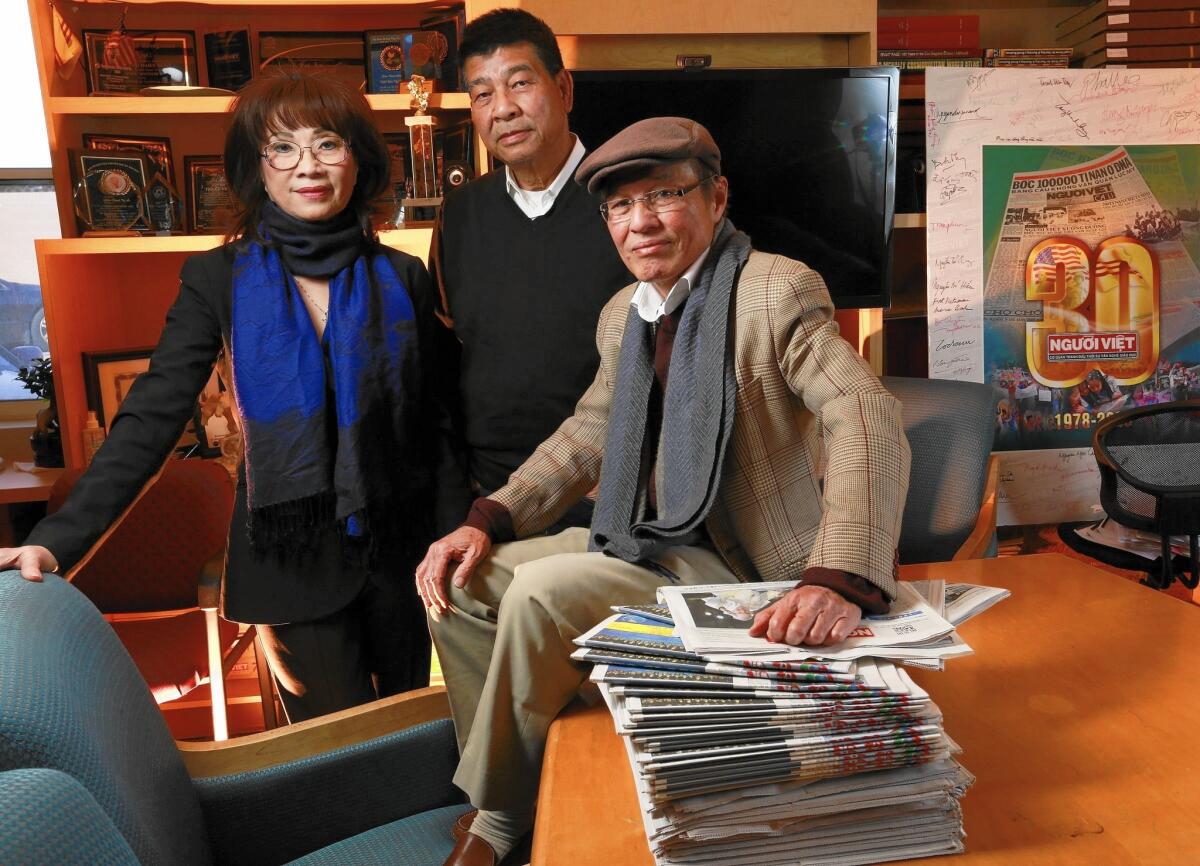

By the fall of 2013, they were representing Nguoi Viet Daily News — America’s oldest Vietnamese-language daily — at a banquet of Vietnamese veterans.

That was when Brigitte Huynh, the publisher of a rival Westminster newspaper, began chastising the organizer for inviting Nguoi Viet — a paper well known, she claimed, for pro-communist sympathies.

The organizer asked Nguoi Viet to leave, and its humiliated staffers — two of whom had been in communist prison camps for 13 years — filed out.

In the Vietnamese American community, nearly 40 years after the fall of Saigon, no accusation possesses a barb more poisonous than “communist.” It is a charge, Nguoi Viet says, that the rival publisher had also made in print in July 2012 by suggesting the paper was a communist front.

Last month, Orange County Superior Court jurors sided with Nguoi Viet in a defamation case it brought against Huynh and her 70,000-circulation national newspaper, Saigon Nho. The result: a $4.5-million verdict, among the largest of its kind in the expatriate Vietnamese community.

Hoyt Hart, the plaintiffs’ lawyer, said rivals often use the epithet “communist” to hurt commercial competitors, but the expense of litigation — and the fear of seeing the accusations repeated — discourages libel victims from filing suit.

Hart said he hoped the libel case would send a clear message and discourage red-baiting, though he was unsure how much it will “chasten” Huynh, the newspaper publisher.

“She clearly has no sense that she’s going to have to take responsibility for any harm she causes.”

The defendant’s lawyer, Aaron Morris, said Huynh’s article was intended to be humorous and satirical in nature. He said it did not accuse Nguoi Viet of communist ownership, which he called a “tortured interpretation” of the text.

“We don’t agree for a minute that anything she wrote was defamatory,” Morris said. The attorney said he believes Nguoi Viet was using the power of litigation to put a competitor out of business.

One of the plaintiffs, Nguoi Viet sales manager Vinh “Vicky” Hoang, 64, said she was physically sickened after reading Huynh’s article, which claimed there were “rumors” about her love life.

After the article, she testified, friends and acquaintances began to look at her differently. “I could not sleep,” she said. “I could not eat.” She said the article’s insinuation of infidelity was like “a huge open scar” on her face.

“My honor and my family has been stepped on,” she said. “I had been educated by my parents to become an honorable woman.” With eight kids and “a husband that I have loved close to over 40 years,” she said, “this is beyond what I can bear.”

During the trial, Hoang spoke of her family’s escape from Vietnam. In 1982, she said, her husband and five of her children fled by boat, but soldiers caught her before she could join them. She chewed and swallowed documents naming her as the boat owner, knowing her punishment would increase if it was discovered.

Nearly three years later, she escaped on another boat, surviving at sea for four days before reaching the safety of an oil platform and, eventually, the United States.

Another plaintiff, publisher Dat Phan, 66, told jurors that as North Vietnamese tanks rolled toward the capital in 1975, he took refuge on an air base and commandeered a plane that took him to safety in the Philippines.

He got a job as a plumber in the United States and learned English by reading Time magazine cover-to-cover each week with the help of a dictionary. After Viet Nguoi published a letter from a reader in July 2012 reflecting a pro-communist stance, and using derogatory terms for former soldiers of the south, Phan apologized to the community.

At trial, he testified that publishing the letter was a mistake and that the assistant editor who allowed it into print was fired. The Saigon Nho article invoked the incident in making its alleged insinuation about Nguoi Viet’s communist ownership.

After the article, Phan said, friends shunned him. Even people who didn’t believe he was a communist decided to keep their distance, just in case.

“My whole life is devoted to the fight for human rights and democracy since my youth,” Phan testified. “And now penning me as an agent, a secret agent of the communists, that’s horrendous.”

He added, “The psyche of our community is that, you know, people are so suspicious because with our experience of the communists.”

Thai Dinh, 60, a distribution manager for Nguoi Viet, said that the Saigon Nho article impeded his ability to sell the paper nationwide and caused friends to ostracize him.

“They don’t want to even call me up to say ‘hi,’” said Dinh, who worked in the anti-communist underground in Vietnam, where he was imprisoned for more than seven years. “They told me it’s not, you know, good time to see each other.”

It is unclear whether Huynh will be able to pay the $4.5-million verdict against her, or whether her publication will survive. Her attorneys said they will appeal.

Under questioning at trial, Huynh denied that she accused the rival newspaper of communist ownership but said it was “recognized by everyone” as pro-communist.

As an example, she cited a 2008 incident in which Nguoi Viet published a photograph of a pedicure basin painted in the colors of the former South Vietnamese flag.

The basin was an art project intended to honor a relative of the artist, a Vietnamese refugee who had worked for years in a nail salon, but protesters interpreted it as a slight against the fallen south.

After complaints from newspaper staffers that they were being harassed, a judge granted an injunction against protesters ordering them not to threaten newspaper employees or trespass on its property.

At the trial, Hart pressed Huynh, 65, to describe her basis for writing that there were “rumors” about Hoang’s love life.

“You have no evidence supporting the truth of the rumor?” asked Hart. “Yes or no.”

“No,” Huynh said. “I have no evidence.”

The lawyer went on. “You don’t care if the rumor is true or not?” he said.

“I don’t care about that, because I think rumor is rumor.”

In an illustration of the supercharged power of seemingly innocuous symbols, Huynh testified that even the newspaper’s name, “Nguoi Viet” — which translates as “Vietnamese people” — evoked questions.

“I just want to emphasize that when they use the word ‘Vietnamese people’ or ‘Nguoi Viet people,’ those terms are only being used by the communists,’” she said.

The plaintiff’s attorney pointed out that Little Saigon was filled with businesses bearing that name, from body shops to fish markets.

It is not the first time Vietnamese Americans have won a defamation suit in a red-baiting case. Nancy Bui, 60, founder of the Vietnamese American Heritage Foundation in Austin, Texas, said her group lost most of its members after a man labeled her a communist sympathizer.

She won a $1.9-million verdict in 2011 and said she regained most of her members.

In 2013, the Supreme Court of Washington State affirmed a trial court’s verdict for $310,000 for a Vietnamese immigrant who accused another Vietnamese immigrant of defaming him as a communist.

Among the pieces of evidence used to smear him, said the plaintiff’s lawyer, Gregory Rhodes, was a cooking apron with an image of Santa Claus that his accuser said was a depiction of Ho Chi Minh.

christopher.goffard@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.