Historic Lummis House faces an uncertain future

- Share via

He walked into Los Angeles a bigger-than-life figure and built a legacy with his own hands and imagination on the edge of the Arroyo Seco.

Charles Fletcher Lummis spent 143 days hiking from Cincinnati to get to Los Angeles in 1885, an odyssey he chronicled in dispatches to his hometown newspaper in Ohio.

He would go on to become a reporter at the Los Angeles Times and, with his workaholic nature, was named the paper’s first city editor. After a stroke left him partially paralyzed, Lummis became the city’s librarian, wrote books on the Southwest and helped launch the Southwest Museum.

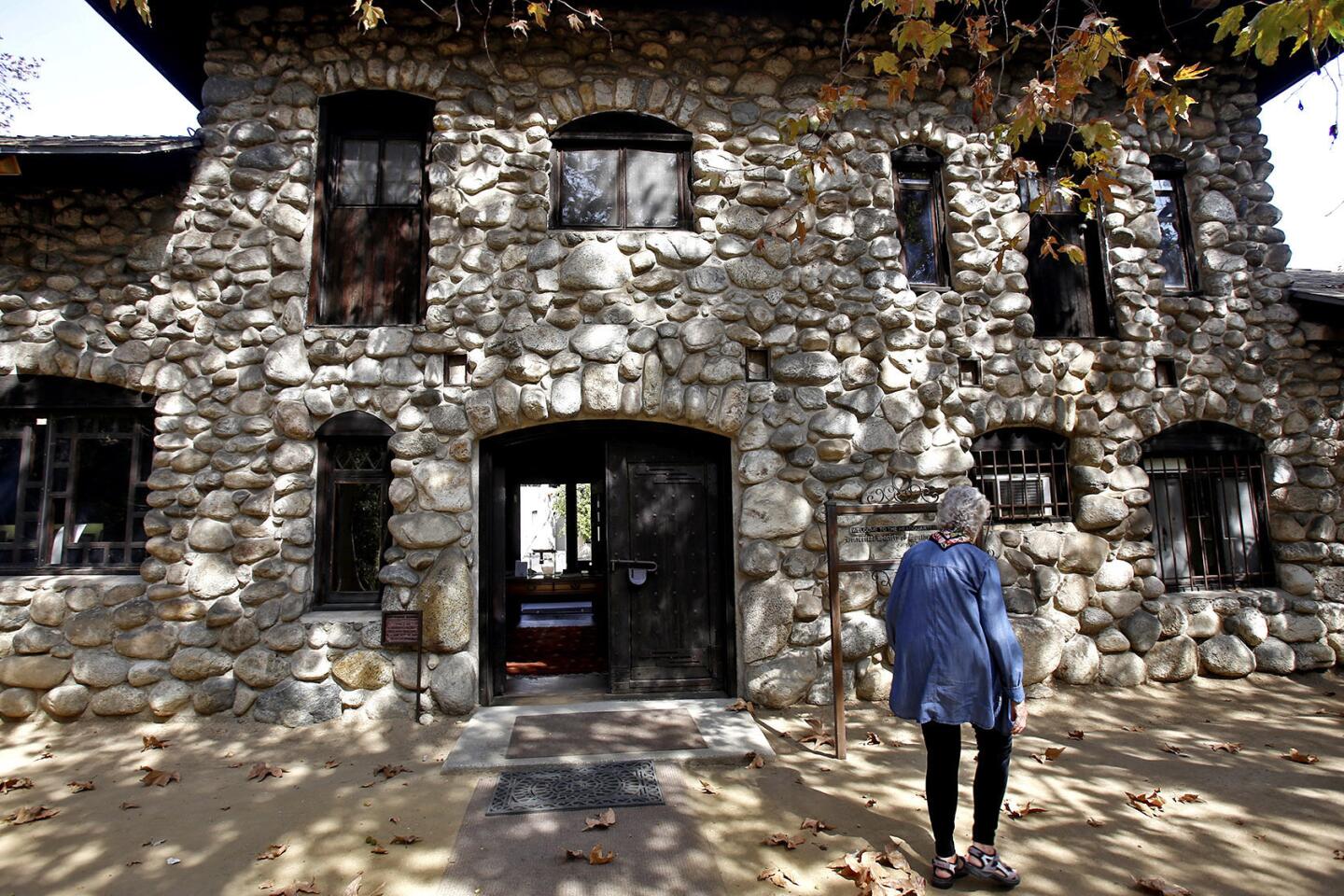

But it was the rustic Craftsman-style home built with river rock in a grove of sycamore trees in Highland Park, however, that seemed to best capture the man.

Now, after decades of being one of Los Angeles’ curiosity pieces, the Lummis House faces an uncertain future as its longtime tenants — the Historical Society of Southern California — prepare to move out and put many of their artifacts into storage.

The house, cobbled together with rounded boulders from a stream, was built on a three-acre lot Lummis purchased in 1897 and named “El Alisal,” in tribute to the thicket of alder and sycamore trees that grew in the arroyo. It took him 13 years to build the 4,000-square-foot home.

The detail work is impressive: A castle-like turret built of river rock. A basement he dug himself and used as a darkroom for printing his collection of photos of the Southwest. And the glass-plate images he made and used as window panes.

When the house was completed, Lummis invited artists, writers and musicians to parties that were held in an exhibition hall that had a concrete floor so that it could easily be cleaned with a bucket of water. He built guest houses for those who spent the night, including such dignitaries as Clarence Darrow, humorist Will Rogers, composer John Philip Sousa and naturalist John Muir.

Before Lummis died in 1928, the home was acquired by the Southwest Museum and was later sold to the state, which transferred the property to the city’s Department of Recreation and Parks. In 1965, the Historical Society of Southern California moved in and maintained it as the society’s headquarters, opening it to the public.

But the society’s long-standing lease with the city has not been renewed, said Patricia Adler-Ingram, the 450-member society’s executive director.

“Recreation and Parks says we have a right of entry until the end of the year working with our month-to-month leasehold. We don’t know where we’ll move,” said Adler-Ingram, 93. She said the society’s board is not convinced that it needs a headquarters because it has operated without one for much of its 130-year history.

But without a place to display the society’s books, journals and other artifacts, they will be placed in storage and the Lummis House’s future will be up in the air.

Ariel van Zandweghe, who has been curator of the Lummis home for eight years, said the society’s efforts to reach a long-term lease ran into problems because the city wanted to enter into a partnership with a tenant that would invest in the house.

“The historical society has been preserving and restoring things like these windows and the lights with members’ own money,” he said. “Some members feel rightly we shouldn’t be putting money into a property that doesn’t belong to us and we don’t have long-term control over.”

Occidental College has expressed an interest in using the Lummis House as the base for an institute of western history.

“Lummis was such a peculiar and admirable figure,” said Jeremiah Axelrod, 44, an Occidental history professor who has led the effort to use the Lummis House. “He is a great window on the past.”

But he cautioned that Occidental would also require a long-term lease from the city before creating such an institute. Axelrod said school groups would still be allowed to take tours and the historical society would probably be invited to continue using the house.

Vicki Israel, an assistant general manager with the Department of Recreation and Parks, said the city’s concern was that the historical group was not truly focused on a partnership.

“The historical society was focused on their headquarters, not the Lummis Home. They love the Lummis Home,” she said. “But it was hardly open to the public.”

Twitter: @BobsLAtimes

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.