Living, under many names

- Share via

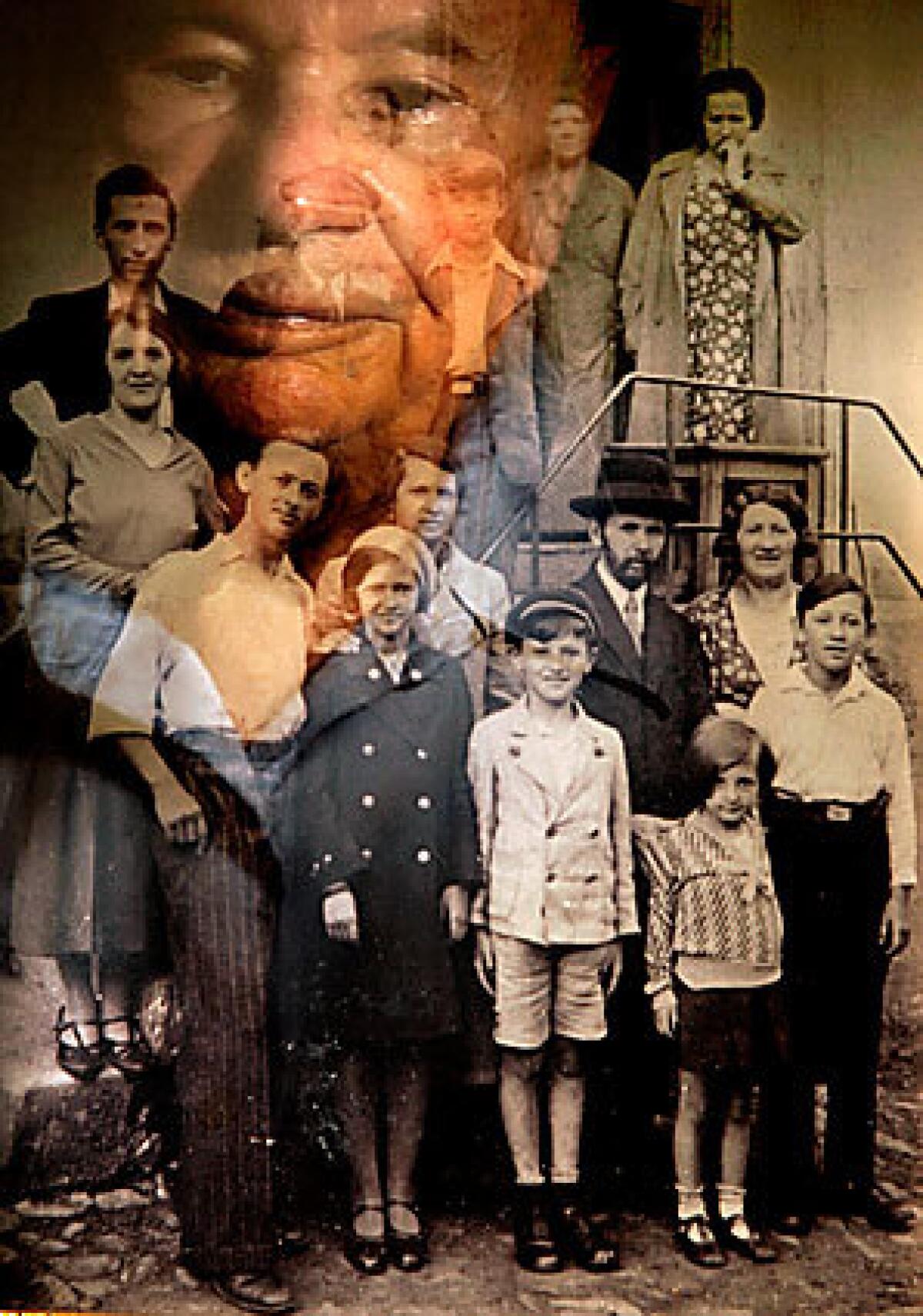

In his 89 years, Sol Berger has gone by many names.

FOR THE RECORD:

Holocaust survivor: An article in Monday’s Section A about a Polish Jew who used several identities to evade the Nazis during World War II misspelled the names of the towns of Debrecen in Hungary and Cluj in Romania as Debracin and Klush. —

He started life in Poland as Salomon Berger, then became Jan Jerzowski. Then he was Ivan Marianowicz Jerzowski, then Shlomo Harari, then Sol.

During World War II and its aftermath, the names kept him safe, protected him from the concentration camps and eventually allowed him to seek refuge in the United States.

But the names also forced Berger, a young Jew, to live in constant fear as he assumed identities that included a Polish partisan fighter and a Russian lieutenant. With each name, and each life story he had to remember, a little more of the real man was kept hidden.

After the war he settled in Los Angeles and began to build a new life, this time as Sol Berger. For decades he never spoke about what he endured as Jan, Ivan and Shlomo.

But as Berger came to discover, those identities, though fake, were an integral part of his life story. And to honor the memory of parents and siblings who died in the war, he had to tell the world how and why he came by so many names.

Salomon Berger (1940-1942)

Salomon was beaten badly.

“He’s had enough today,” he heard a Nazi say after two hours of questioning. When his interrogators left the room, the 20-year-old Salomon sensed his chance. Rail-thin at about 100 pounds, he eased himself through a small window that had barbed wire attached to its frame and let himself down from the second story.

Salomon had been arrested because he had refused to report for a forced labor detail. After escaping, he hid in a nearby Jewish home but later made the mistake of returning home to southeastern Poland. It was 1940, the year after Germany invaded.

“I thought nobody was going to know who I am,” he recalled decades later. “I came back to Krosno after three weeks, and the Gestapo was waiting for me.”

Gestapo officers knew what Salomon looked like because they had been using his family’s tailor shop to clean and mend their uniforms. He was thrown into a political prison with 10 Catholics, including a priest who said Mass and lectured on Christianity daily. Salomon listened carefully. After six months, his parents bribed officials for his release.

Life attained a kind of normalcy, but over the next two years rumors trickled in of deportations and gas chambers.

The story of what happened next is based upon Salomon’s recollections and documents. Records maintained at Yad Vashem, an Israeli Holocaust museum, verify that Sol and other family members lived in Krosno during the war. Aaron Breitbart, a senior researcher at the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, says that key details of his accounts conform with the historical record.

As Salomon remembers, and as Breitbart confirms, Krosno’s Jewish community received its “resettlement” orders on Aug. 9, 1942, and the town’s 2,500 Jews reported to the marketplace at 9 the next morning. Salomon’s father was grouped with 500 elderly men and women and told to get on a truck. Salomon started to cry.

“This is goodbye,” his father said to Salomon and his three brothers. “I know nobody is going to come back from these trips. But I want you to make me a promise. You boys try to survive any way you can, to be able to tell this story.”

The trucks returned empty.

Salomon and his brothers -- Moishe, Michael and Joshua -- were among 600 others pressed into forced-labor crews in the area.

Three of his five sisters had already immigrated to the United States and a fourth had died in anti-Jewish violence in Germany in 1938. But his mother and remaining sister were still in Poland. Both were taken in cattle cars to the death camp Belzec and gassed.

A portion of Krosno was blocked off as a ghetto. A month later, the Gestapo took away another 100 people, including Michael and Moishe.

That left just Salomon and Joshua. Soon after, the pair found someone who sold false identity papers. As Jan Jerzowski, a good Christian name, Salomon left Krosno. The day after the brothers escaped, the ghetto was liquidated.

Jan Jerzowski (1942-1944)

Jan was on a train headed to Eastern Poland when police asked for his papers.

They lingered and asked if he took Communion. He assured them he did. Still not satisfied, they asked him to say a prayer. Remembering what he learned from the priest, Jan recited the Lord’s Prayer.

The police let him go.

Joshua was not so lucky. The brothers had split up for the night, and Joshua was never seen again.

Jan moved on to Niznow, where he found Tadeusz Duchowski, the husband of a family friend who had helped him escape Krosno. Duchowski supervised a construction crew on a bridge, and Jan joined the other workers, all of them Christians.

Duchowski could not put Jan on the books -- listing an extra worker might raise suspicions -- and he did not have money to pay for one more laborer. But the work served as a cover. For money, Jan did tailoring on the side; he had also squirreled away 30 American dollars, purchased on the black market, by sewing them into his clothing.

One day, a member of the crew pulled him aside and said, “Let’s go for a walk.” The man looked inquisitively at Jan. “Are you . . . . ?”

“No, I’m not,” Jan said, cutting him off.

The conversation shifted to the war. And then the man gave him a few words of advice.

“Let me correct you on two items,” the man said. “When you drink tea and you have cube sugar, put it inside [the cup], never bite it. And never eat” sunflower seeds.

“Why?”

“Because Jews have the habit of this type of eating and drinking.”

Then he pointed out a few words Jan spoke with “an accent.” Jan never admitted he was Jewish, but he listened carefully. At night he worried he would give himself away by talking in his sleep.

After three months, the bridge was completed and Jan teamed up with Polish partisans who fought the Germans by planting mines on railroad tracks and committing other acts of sabotage.

One time he heard one of his comrades say that, although the Nazis were horrible, “they killed the Jews for us.”

He pretended to be a boisterous fighter. Some of his fellow partisans spoke Russian, so he began to pick up the language. He would force himself to down glasses of homemade vodka and then sneak away to vomit. When they came upon a river and had a chance to bathe, Jan left his underwear on so others would not see that he was circumcised.

Once, when questioned by a German officer while leaving a train on a mission for the partisans, he replied in Polish, “I don’t understand German,” even though he did. He knew that Christian Poles rarely spoke German; Jews, with their Yiddish, were more likely to understand the language.

The officer let him pass.

In March 1944 the Russians arrived in Poland, and Jan was forced into the Soviet army. He was given new identity papers, now with an appropriately Russian name. Because the father of Jan Jerzowski was listed as Marian, he would now be Ivan Marianowicz Jerzowski.

Ivan Marianowicz Jerzowski (1944-1945)

Many Polish partisans and other newly enlisted Russian soldiers were sent to the front lines, but Ivan did not want to die. He spotted a German prisoner with a gold watch and took it, to barter for his life with a Russian commander. Ivan could speak Polish, Russian and German, he noted. Couldn’t that be of use?

Ivan, now 25, was put to work in the interrogation department translating the questioning of German prisoners. In April 1945 he took a leave from the army and began searching for surviving family and friends. Along the way, he learned that his brother Moishe had been hanged in Auschwitz.

For the last few years, Ivan had played with the idea of remaining a Catholic. He had lived as one for so long, going to church every day, that Christianity felt engraved in his mind -- and life was easier as a Christian than as a Jew.

But once he reunited with other Jews in Krakow, he embraced his heritage. “I don’t want to live a life of lies,” he said to himself. “I am born Jewish, I survived, and that’s what I’m going to be.”

He sought out a Jewish committee that was helping concentration camp survivors get false identity papers needed to travel to Palestine. At the committee headquarters, he met a beautiful young Polish woman named Gusta Friedman. She had survived the war posing as a Christian, using the name Waldislava Urbanska.

Ivan introduced himself.

“I don’t go out with Russians,” she told him, eyeing his uniform. He was really a Jew, he told her, and he would leave for Palestine the next day. If she wanted to join, she should come to the headquarters at 10 a.m.

The next morning, she was there.

They planned to travel to Romania, where ships could be found for Palestine. But Ivan heard that gaining entrance into the country would be easier for people from southern Europe than for those from the north. It meant another alias.

Shlomo Harari (1945)

He took off the Soviet uniform and put on a brownish green suit he had bought in Krakow. He was bound for Romania via Czechoslovakia on an open cattle car, one of millions of people crisscrossing Europe searching for survivors and a new life.

“I became Shlomo Harari, a Greek going back home.”

On May 7, 1945, the train pulled into Debracin, Hungary, and passengers spent the night on the floor of a school. In the morning, Shlomo woke to cheers and firecrackers. Germany had surrendered.

Two weeks later, Shlomo and Gusta married in the Romanian town of Klush. But there was no honeymoon in Palestine. In Bucharest they learned there were no ships available and instead made their way to a displaced persons camp in Italy.

“And here I became back to Salomon Berger,” he said decades later. “I knew any place I wanted to go, I had to use a proper passport.”

Sol Berger (1946-present)

While contacting his sisters in the U.S. for visa paperwork, Salomon learned that his youngest brother, Michael, had survived Auschwitz and was living in L.A.

It would take five years -- three in the displaced persons camp, where his son Jack was born, and two years in England, before Salomon got the call from the U.S. Embassy in London to come get the family’s visas.

In June of 1950, he arrived at Union Station in Los Angeles. Michael told him: “If they ask you how you survived, don’t talk. Because these people here . . . they say, if you suffered, we suffered here too. We had to stay in line for gasoline. We had to be on a waiting list to get a car, and we didn’t get any steak. . . .”

Salomon lived in West Los Angeles, worked odd jobs and as a tailor and opened a liquor store with Michael near the Coliseum. With his new life he wanted a new name: Sol. It’s the name on his citizenship papers.

At 57, he enrolled at West Los Angeles Community College and studied business law, accounting and real estate. He became a top seller for Fred Sands Realtors in Beverly Hills and prospered, even though he sometimes battled depression, a consequence of the war.

Michael eventually decided that keeping silent about the war made no sense, and he volunteered as a docent at the Museum of Tolerance. Sol, however, still followed his brother’s earlier admonition and never spoke of those hard years.

In 1994, Michael, a chain smoker, was dying of lung cancer. As Sol recalled, “He said to me, ‘I want you to do me a favor, please. I want you to tell the story of survival, and everything else you can.’ ”

After Michael died, Sol walked into the museum for the first time.

In the last 15 years, Sol has spoken to museum visitors up to three times a week. At first it was difficult. He would often break into tears. But it got easier, and telling his family’s story and recounting his days as Jan, Ivan and Shlomo provided a measure of therapy that helped him combat his depression.

He cannot walk very well, but when he speaks, he stands for more than an hour, white wisps of hair dancing on his balding head as he gesticulates to illustrate points.

“This is my calling,” he says.

He had once resolved never to return to Poland and its painful memories, but last December he felt the need to visit Auschwitz, where his brother Moishe died. He said Kaddish, the mourner’s prayer, before a mass grave near Krosno, where his father was buried.

He visited the former ghetto a block from where he grew up. There he met Henryk Duchowski, the son of the couple who had helped save his life. Duchowski calls him “Yashu,” a nickname for Jan. But to all others he was, and remains, Sol Berger.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.