Martin Litton dies at 97; passionate wilderness conservationist

- Share via

As a boy growing up in the 1920s, when California’s population was less than 5 million, Martin Litton would hike cross-country from his Inglewood home to the beach. Sometimes he accompanied his veterinarian father on his rounds to the ranch that later became Los Angeles International Airport.

Litton spent summers camping with his family in Yosemite National Park. As a teen, he and a friend rented a burro, for 75 cents a day, and climbed Mt. Whitney. On that 12-day trip into the wilderness, they never saw another person.

“That was the thing that changed my life,” Litton would recall decades later.

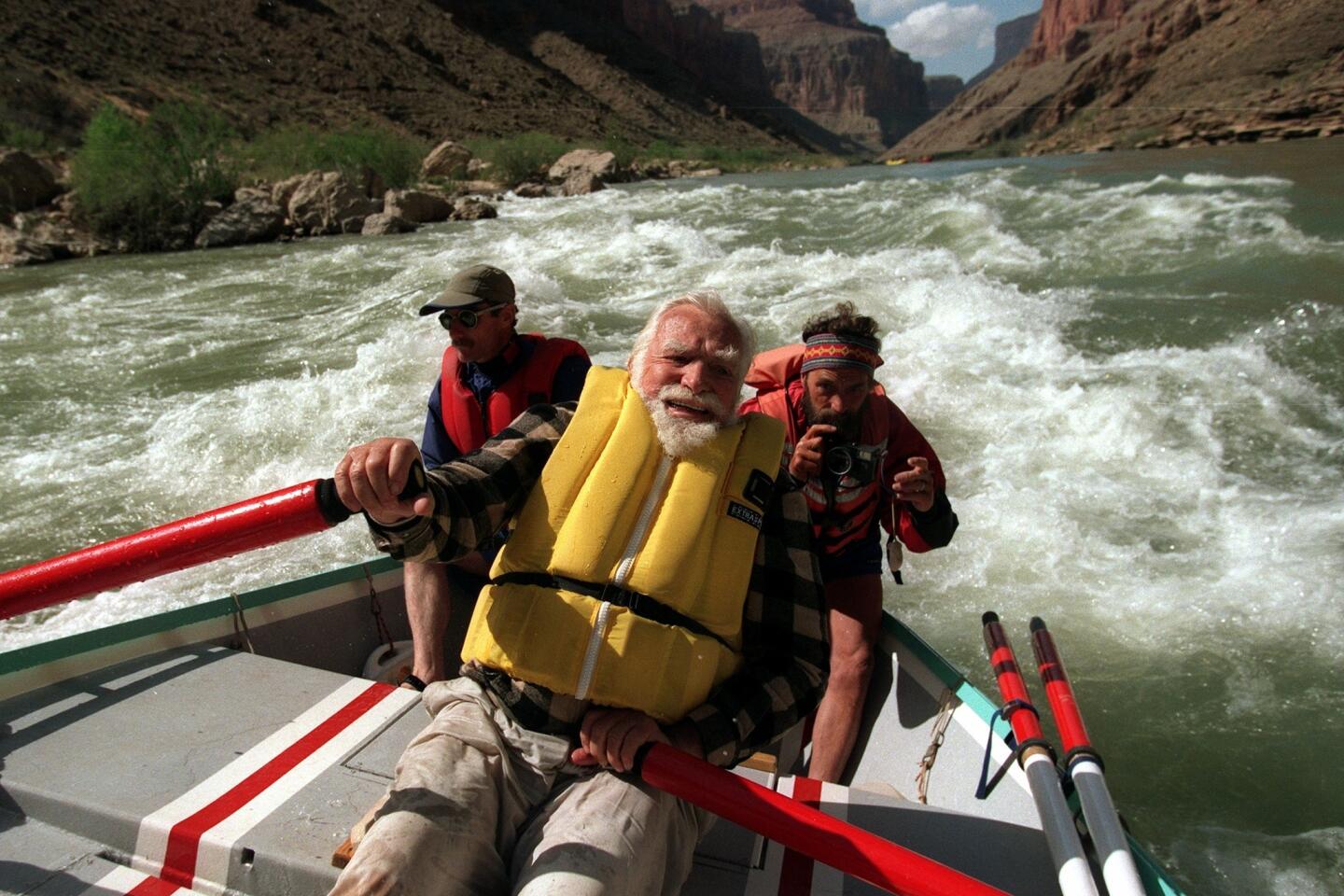

Litton, 97, a legendary Colorado River guide and fierce wilderness advocate involved in some of the 20th century’s biggest conservation battles, died Sunday of age-related causes at his home in Portola Valley, Calif.

A pilot, oarsman, writer and photographer, Litton was above all a passionate defender of the wild. He was an environmental purist who disdained compromise, a master of what a contemporary called “articulate outrage.”

He played a pivotal role in keeping dams out of his beloved Grand Canyon and a ski resort out of the southern Sierra’s majestic Mineral King Valley. He was a leading force in the establishment of Redwood National Park and fought a bitter, losing fight against the construction of a nuclear power plant in Diablo Canyon on the California coast.

The preeminent conservationist David Brower called Litton his conscience. “When I would waver in various conservation battles, he would put a little starch in my backbone by reminding me that we should not be trying to dicker and maneuver,” Brower said. “I guess I got some of my extremism from Martin Litton, and I’m grateful for it.”

Litton was as unyielding to age as he was to those who would destroy the wild. He continued to crusade, pilot his vintage Cessna, row a dory through the Grand Canyon and enjoy a good martini past his 90th birthday. With a powerful voice and strong features wreathed in a white beard and soaring eyebrows, he remained a commanding presence.

“He was no nonsense, fearless, would always speak truth to power,” Bruce Hamilton, deputy executive director of the Sierra Club, said Monday. “He had a way with words, a way with photographs, just a way of shaming people into doing the right thing.”

Litton served on the board of the Sierra Club from 1964 to 1972. As an ally of executive director Brower, he challenged the organization’s gentlemanly old guard, persuading — some would say bullying — the board into reversing its position and opposing the Mineral King development. He made sure the club didn’t acquiesce to government proposals to erect two dams on the Colorado in the Grand Canyon.

“If I hadn’t done what I did, I think it’s very likely at least one of those dams would have been put in the canyon. I was the only one screaming about them,” Litton said in a 2011 interview with the Los Angeles Times.

Like Brower, he regretted that he had not fought harder against the upriver construction of Glen Canyon Dam. “I knew it was a beautiful place. There were just so many things to be concerned about. It had to take a back seat, and that’s too bad.”

Clyde Martin Litton was born Feb. 13, 1917, in Los Angeles. He launched his first environmental crusade while he was a student at UCLA, where he met his future wife, Esther Clewette. Litton and some friends formed a group called California Trails to keep roads out of wild places. They succeeded in stopping a highway that would have sliced though the High Sierra to connect Lone Pine and Porterville. The area eventually became the Golden Trout Wilderness.

He majored in English because he thought it would be easy. After graduating in 1939, he worked briefly as a teacher and in public relations for an Arizona resort, then got a job as a part-time tour guide at the Los Angeles Times. After World War II, during which he served as a glider pilot in the Army Air Forces, he returned to The Times in the circulation department.

The job kept him on the road a lot, and when Litton came across an interesting story, he freelanced it for the paper. The Times paid him $10 a photo and 75 cents a column inch. Before long, he was writing articles with pointed environmental themes, making no attempt at impartiality as he warned of government dam-building plans that would flood parts of Dinosaur National Monument and the Grand Canyon.

Vividly written and illustrated with his photos, the articles caught the attention of Brower, who enlisted Litton to contribute to Sierra Club publications. When Sunset magazine was looking for a travel editor, Brower recommended Litton, who moved to the San Francisco Bay Area to take the job in 1954.

The magazine shied away from controversy. So Litton, who became senior editor, used pseudonyms in his club work, including photos published in “Time and the River Flowing,” the crusading 1964 book on the Grand Canyon.

That same year he was elected to the Sierra Club board. He was soon stirring things up. “I sort of ran my own course while in the Sierra Club,” Litton recalled in a series of interviews of club figures conducted by the oral history project at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library. “I didn’t feel cooperation even within the club was necessary. I thought dissent and ferment, or whatever you want to call it, might be essential.”

Several avid skiers were on the club board, which was preparing to support Walt Disney Production’s proposal to fill Mineral King’s mountain bowls and valley with downhill ski trails and a year-round resort. A new road to the development would have cut through nearby Sequoia National Park.

“I stood up in outrage and said, ‘How dare you! How dare anybody even think about this!’” Litton said. “I remember [longtime board member] Ansel Adams saying, ‘I didn’t know [the road] was going to be in the national park.’ I said, ‘All you have to do is look at the map, dumbhead.’”

The board reversed its position, fought the proposal and Mineral King was never developed. The area was later added to the park.

Alternately eloquent, charming and abrasive, Litton alienated some on the board, which in the 1960s was divided between warring pro- and anti-Brower camps. Litton wasn’t much of a smoker, but during board meetings he would sometimes puff away on big cigars just to annoy people.

“There was always something that Martin was thoroughly exercised about, and he could be brutal in his remarks,” fellow director William Siri said in the Bancroft Library interviews. “Martin was never the environmental statesman, but he was fascinating as a speaker. He used colorful phrases, analogies and metaphors and they were often cutting, sometimes irresponsible. He never pulled his punches. He was never inhibited; if he felt something, he just said it.”

Litton, who rowed crew at UCLA, first floated down the Grand Canyon in 1955 with a group that included his wife. At that point, fewer than 200 people were known to have made the trip. Litton had dislocated his shoulder and was just a passenger. But he was hooked. The next year he rowed through the canyon, and until he was in his early 90s, returned again and again to ride the Colorado’s heaving, stormy rapids, which he called the best in the world.

His river passion grew into a full-time job after he quit Sunset magazine in a huff in 1968 because publisher Bill Lane killed an article he had written about acreage omitted from the new Redwood National Park. He founded Grand Canyon Dories and until the late 1980s ran commercial trips through the canyon in nimble wooden boats he and a friend had adapted from the Northwest river dory.

Litton’s big hands were most comfortable wrapped around dory oars or the controls of a small plane. He had piloted gliders loaded with troops and equipment during Allied invasions in Europe. Decades later he would fly politicians and journalists in his vintage Cessna, skimming over redwoods or landscapes that needed saving, expounding on the glories of nature untamed.

“Nature has its rights,” he once said. “It has a right to be here untrammeled, unfettered. Man doesn’t have to screw everything up.”

Litton is survived by his wife, Esther; children John, Donald, Kathleen and Helen; five grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Twitter: @boxall

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.