Milton Hebald dies at 97; creator of prominent public sculptures

- Share via

Most art lovers won’t recognize the name Milton Hebald. But it’s safe to assume that tens of millions of people have seen his work: sculptures, installed in prominent public places in Los Angeles and New York City, that include a monumental display of the 12 signs of the Zodiac that stood for decades at New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport.

Outside the front entrance to the Stuart Ketchum Downtown YMCA in Los Angeles, visitors dropping in for a workout pass Hebald’s 1986 “Olympiade ‘84,” a bronze depicting three women racing in full stride, their pony tails flying. Around the side of the building is “Handstand,” a statue of a boy performing that athletic move one-handed atop a narrow pedestal.

In New York’s Central Park, Hebald’s statues of an embracing Romeo and Juliet and of Prospero and Miranda from “The Tempest” stand outside the Delacorte Theater, where stars perform each summer in the Shakespeare in the Park series.

For more than 30 years starting in 1961, Hebald’s 200-foot-long “Zodiac Screen” hung against a curtain of glass at the entrance to the international terminal of the now-defunct Pan American Airlines at JFK Airport. For many arriving foreign travelers – possibly including the Beatles, who came through the terminal in 1964 on their first visit to the United States -- it was their first glimpse of art on American soil.

Pilgrims to James Joyce’s grave in Zurich, Switzerland, continue to have their reveries fed by Hebald’s 1966 life size bronze capturing the great modernist author deep in thought, with open book in hand.

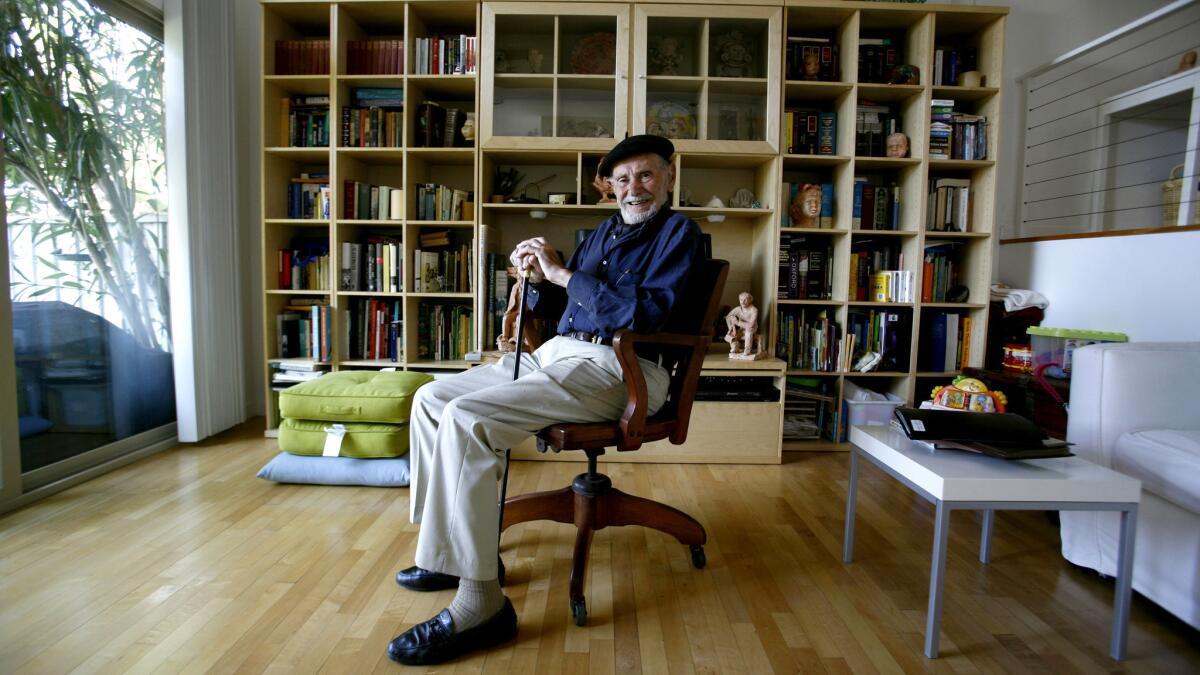

Hebald, 97, died Monday at an assisted living facility in West Hollywood where he spent the last year of his life. His granddaughter, Lara Hebald Embry of Culver City, said he had continued to sketch on paper and occasionally sculpt in clay until his death from heart failure.

Interviewed by the Los Angeles Times in 2010, Hebald, then 93, had a simple explanation for why his urge to sculpt and draw hadn’t let up in old age: “They make me happy,” he said. “That’s what they’re for. I wake up each morning and want to get to work.”

Hebald’s death ended nearly 90 years of art-making. He was born May 24, 1917, in New York City into what his daughter, architect Margo Hebald, described as a “relatively affluent bourgeois family.” Hebald was 8 when the public had its first glimpse of his talent -- a drawing of the Manhattan skyline that McCreery’s Department Store published in a children’s magazine it sponsored.

His father, Nathan Hebald, was an immigrant from Krakow, Poland, who married American-born Ava Elting and opened a jewelry store in the Bowery in Manhattan. Hebald was 6 when his father was shot dead in a robbery at the store, according to Frank Getlein’s 1971 book, “Milton Hebald.”

Hebald left home at 16, his daughter said, and began attending art schools in the city. In his late teens, he landed his first paid job as an artist: Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration, a program to put unemployed people to work on federally funded projects during the Great Depression, sent him to an Italian neighborhood on Manhattan’s Upper East Side to teach kids how to work with clay. The WPA also provided Hebald with one of his first public art commissions, “Boating on Barnegat Bay,” a 1941 wooden bas relief at a post office in Toms River, N.J.

The WPA’s inclusion of artists as workers in need of jobs provided “a complete start in the art world for me,” Hebald recalled in 2010, when three of his smaller sculptures from that era were being featured in an exhibition on art funded by Roosevelt’s New Deal at the Bedford Gallery in Walnut Creek, Calif.

Hebald landed on a different federal payroll in 1945, when he was drafted into the U.S. Army. His career began to blossom after his military service. The Whitney Museum of American Art bought his 4-foot-tall wooden statue, “Woman With Birds,” in 1948 -- although Hebald would go on to be represented far more on the nation’s sidewalks than in its museums, where abstract sculpture dominated the postwar scene. Museum curators were less interested in the strictly realistic renderings of athletes, dancers, lovers (a favorite subject), and creative artists that were Hebald’s forte. Among the arts figures he sculpted were folk singer Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, opera star Richard Tucker (a Hebald bust of the singer adorns a small square next to Lincoln Center), Joyce and “A Clockwork Orange” author Anthony Burgess.

Reviewing a Los Angeles gallery exhibition of Hebald’s sculpture in 1965, Los Angeles Times art critic Henry Seldes concluded that “Hebald, though greatly gifted, is simply inconsequential.”

Said Kenneth Pushkin, whose gallery in Santa Fe, N.M., sells Hebald’s remaining work: “His work was very positive and bright. He liked playful, joyous moments that celebrate the human spirit in its best light.”

A turning point, for Hebald, in 1955, was winning the Prix de Rome, a three-year fellowship for art students that brought him and his wife to the Italian capital. With Italy’s superb bronze foundries and cheap living as initial inducements, Hebald made Rome his base for nearly 50 years.

Embry, the artist’s granddaughter, said that at his peak in the 1970s and 1980s, Hebald commanded up to $80,000 for privately commissioned bronzes.

He returned to the United States in 2004 with his second wife, actress Kathleen Arc, settling in Santa Fe; Cecille had died in 1998. After Arc’s death in 2006, Hebald, who’d become isolated from the rest of his family during the second marriage, wound up alone in a nursing home in Santa Fe. A difficult period ended in 2008, when Hebald reconciled with his family and came to L.A. to be near them. He mainly shared a home in Sherman Oaks with a much younger cousin, Alan Wald.

As an Angeleno, Hebald gave art classes at a senior center in Culver City and at the Alpert Jewish Community Center in Long Beach, which mounted “Thoughts That Transcend Time,” a 2009 exhibition of small clay sculptures he’d created in L.A. His art students included his great-granddaughter, Cecille, and classmates at her nursery school in Culver City.

To the end of his life, Embry said, her grandfather kept active and dreamed of seeing “Zodiac Screen” taken out of mothballs (its owner is the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey) and restored to public view.

While he didn’t live to see that dream fulfilled, Karen Lupton, who’s in charge of the Milton Hebald Trust that controls his work, said Tuesday that a benefactor she declined to identify is working to find a new spot for the towering Zodiac signs, where they can resume being on constant view as public art.

“There are good efforts underway, with the right kinds of people” to see Hebald’s wish realized, Lupton said.

Besides his granddaughter and his daughter, who designed Terminal One at Los Angeles International Airport, Hebald’s survivors include his grandson, Sergei Hebald Heymann of Tokyo; and his great-granddaughter, Cecille Tuccillo of Culver City.

Twitter: @boehmm

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.