Pete Dupuy dies at 79; vocal opponent of commercial fishing regulations

- Share via

On Dec. 7, 1973, San Fernando Valley motorcycle salesman Pete Dupuy took off in his Cessna plane to meet a couple of friends at a camping area in Mexico.

Exactly what happened there became a matter of bitter dispute, but Dupuy’s airplane ended up riddled with bullet holes, he was jailed in Mexico for nearly a year and a half on suspicion of drug trafficking, and back in the U.S. much of his property was seized.

Eventually, Dupuy was absolved of wrongdoing. One judge called the actions taken against him by tax authorities, who contended he owed money from illicit income, “tyrannical.”

Dupuy, who for the last several decades headed a commercial fishing operation based in Ventura and was a vocal opponent of government regulations on the industry, died April 16 at his home in Tarzana. He was 79.

The cause of death was cancer, said his wife, Karen.

At the time of the ill-fated Mexico trip, Dupuy (pronounced du-PWEE) was known as an outdoorsman. He said the only aim of his trip was to spend a week with his buddies camping along the Colorado River.

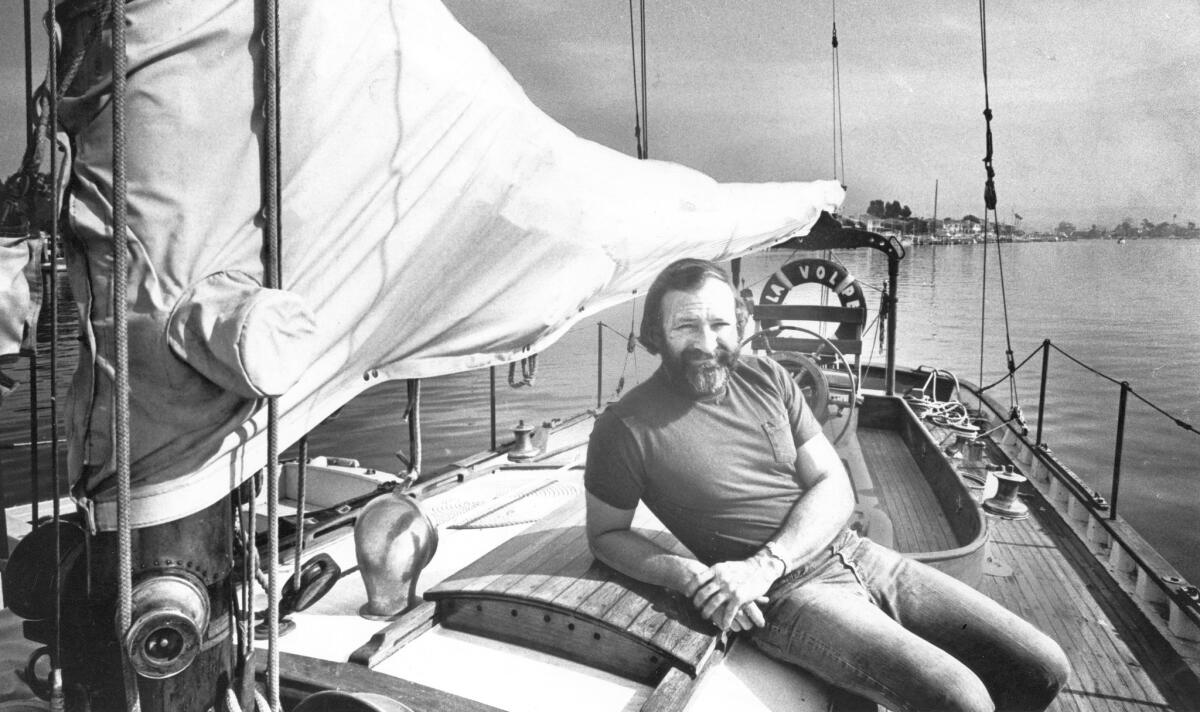

But U.S. law enforcement authorities said he had been under surveillance because of suspicions he was using his plane as well as his 45-foot schooner to smuggle large amounts of marijuana into the country. Authorities later acknowledged, however, that they had never observed Dupuy nor his friends in possession of illegal drugs or bundles of cash for transactions.

Dupuy’s friends were arrested by Mexican police before he landed, as was a man in a nearby car that held more than 400 pounds of marijuana. Police said Dupuy’s plane was shot because they believed he was trying to quickly get back in the air after landing.

He and his friends were held in jail for 17 months in Mexico before being cleared by a judge. No charges were filed in the U.S., but tax officials, who had seized Dupuy’s property and alleged he owed hundreds of thousands of dollars from illicit income, did not give up easily.

The case, which made it to the state Supreme Court and into the news, dragged on for years before federal and state officials dropped claims against him. Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Raymond Roberts, who heard part of the case, scolded state tax authorities.

“You are going to ruin him,” the judge said, “and then after you have ruined him, you are going to say, ‘Too bad, old man, we made a mistake, but we are the state, and you can’t do anything about it.’”

He was born Pierre Roland Dupuy on Sept. 25, 1935, in Los Angeles.

After the Mexico incident and its aftermath, he eventually turned to commercial fishing. He spent part of the year in the Cape Cod, Mass., area to catch swordfish, and the rest of the year he would fish off the Ventura County coast. He organized the Ventura County Commercial Fishermen’s Assn. to battle regulations that he and others in the industry felt were too strict.

“Fishing is hard work, but it was simple work,” he said in a 1999 Los Angeles Times interview. “It’s not much like that anymore.... There’s so much other stuff you’ve got to keep an eye on and worry about that you can’t just think about fishing.”

In his mid-60s, he waged an unsuccessful fight against restrictions on fishing in the Georges Bank area off Cape Cod that authorities viewed as overfished.

With his financial reserves depleted from the legal battle, Dupuy put off thoughts of retirement and concentrated on the West Coast, taking his 87-foot Ventura II boat hundreds of miles offshore to use lines up to 40 miles long to snag tuna, dorado and other fish. In addition to the crew, a required federal observer was aboard to ensure procedures were followed to curtail the snagging of restricted sea life.

As the boat made its way back to harbor, email alerts went out to 5,000 people on his company’s mailing list, letting them know when the Ventura II would dock and start selling the fish — whole and filleted — just off the boat. The fish not sold directly was iced and shipped elsewhere.

Despite the frustrations he found with the work, there was still something about it that attracted him.

“It’s real,” he said in The Times interview. “When the water splashes you on the face, you feel free, you feel close to nature.”

david.colker@latimes.com

Twitter: @davidcolker

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.