They were here first

- Share via

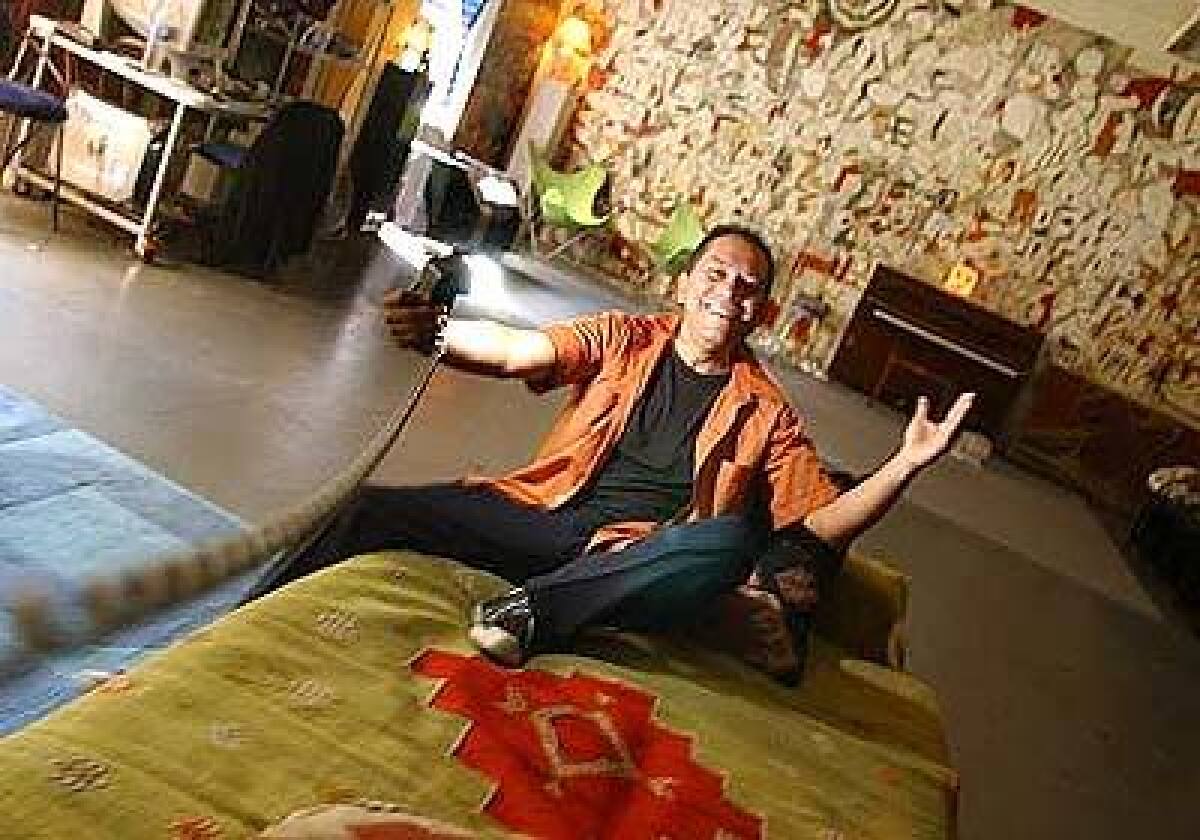

Though the artist known as Gronk has lived in the same funky, baroquely attired Spring Street loft for the last 14 years, you could say that he is really, at heart, a street person. You’re just as likely to find him pounding the downtown pavement in his red Converse high-tops — browsing the mom-and-pop tiendas along Broadway, eyeing a fluorescent slice of pie at Clifton’s Cafeteria, or hopping the Gold Line train from Chinatown to the Pasadena Trader Joe’s, where he’s careful not to buy more than he can carry home in one trip.

“That’s one of the ways you learn to survive down here, is shopping for 15 items or less,” says Gronk, a painter, set designer and conceptual performance artist who has collaborated with the likes of director Peter Sellars and the Kronos Quartet, and whose richly enigmatic, neo-expressionist paintings and prints fetch hefty prices.

Since the late 1970s, when a few intrepid souls with more creative zeal than cash flow began rehabbing abandoned warehouses into live-work spaces, artists like Gronk have formed the backbone of residential downtown Los Angeles. For decades they’ve put up with the area’s inconveniences (no supermarkets, spotty public transportation, skanky sidewalks) in exchange for being able to tap its freewheeling and dynamic ambience.

From the Brewery arts colony northeast of Chinatown to the Staples Center and beyond, artists have brought creative vision to L.A.’s central core, which many middle-class Angelenos gave up on generations ago. To Gronk, downtown remains the heart of L.A., and “the heart of L.A. is 7th and Broadway,” a neighborhood that’s constantly being re-imagined and remade by those who make their homes there.

“It takes a certain kind of person to be here, I think,” Gronk says. “Sometimes people who come here want to make significant changes overnight, and like anything else, it’s a process.”

While downtown’s heyday as a low-budget mecca for artists may be over, the reverse-migration movement that they started in the ‘70s and ‘80s is gaining speed: The recent surge in loft-conversion and residential construction projects that already has brought thousands of new residents to downtown coincides with this month’s official opening of the $274-million Frank Gehry-designed Walt Disney Concert Hall. Finally, downtown may be ready to emerge as a bona fide, full-service neighborhood, as well as the region’s premier cultural hub.

As a result, artists like Gronk increasingly find themselves living side by side with a variety of newcomers. Besides actors, playwrights, painters and musicians, downtown is home to lawyers, emergency medical technicians, architecture students, film industry professionals and Orange County empty nesters. “You tend to notice the recent arrivals because they’re usually wearing flip-flops and they’re walking a dog,” Gronk says with a chuckle.

John Belluso, a playwright (“The Body of Bourne”) and director of the Mark Taper Forum’s Other Voices program for disabled artists, has lived in the Promenade Towers at the edge of Bunker Hill since moving here from New York City about three years ago. He loves being close to the Taper and the Byzantine-Egyptian Central Library, where he often goes to read. The city’s tumultuous atmosphere energizes his work.

“Sometimes I go out on my patio with my laptop and do some writing there,” he says. “Then I oftentimes will go [to] the Marriott. I go to the restaurant or sit with my PowerBook in the lobby. It’s definitely the company of other people that inspires me more than solitude. I’ll never be a nature poet.”

Elizabeth Cook-Shen, a horn player with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, has lived downtown since moving here from Houston in 1995. She and her husband, a classical conductor, reside in a two-bedroom apartment in Bunker Hill Towers, with a front-row view of Gehry’s curvilinear structure. A number of her Philharmonic colleagues live in the same building.

“I originally moved downtown because I didn’t know anything about Los Angeles, and I thought it would be a good place to get to know the area and the highways,” she says. “I ended up loving it down here so I just never wanted to move away.”

Not surprisingly, Cook-Shen appreciates her home’s close proximity to her place of employment. Once, the elevator in her building wasn’t working and she had to run down 28 flights of stairs to get to a rehearsal at the Music Center. “I was almost late, but I made it.”

But she also likes being able to pop out to Sushi Boy or Koo Koo Roo for takeout, going for walks in nearby Echo Park, and the boon of not having to commute on weekdays so that she and her husband can explore other parts of L.A. on weekends without begrudging the drive time. “When you live downtown you can just look out your window when you’re bored and see people doing stuff,” she says. “One day I looked out my window and saw Jennifer Lopez filming a video.”

To Gronk, these surreal contrasts are part of what makes downtown so compelling a place for an artist. “I always refer to living in downtown L.A. as if I were living in a Fellini movie,” he says. “It’s like seeing ‘Satyricon’ on a daily basis.”

Downtown’s reputation as an artists’ haven is well-earned. When painter Jon Peterson graduated from Otis Art Institute (now Otis College of Art and Design) in 1976, he found a 2,500-square-foot loft in a five-story brick building, a former garment factory, just south of St. Vibiana’s Cathedral in Little Tokyo. His monthly rent was $75. Because the city’s building and safety inspectors weren’t paying much attention to the new artist enclaves at the time, an improvisational, risk-taking subculture took root downtown.

By the mid-’70s, Peterson says, several dozen L.A. artists including painters David Amico and Andy Wilf and sculptors Woods Davy, Rick Oginz and Colleen Sterritt were living downtown, paying virtual pittances for live-work spaces the size of small concert halls. Another early arrival was Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), the avant-garde, multidisciplinary forum that quickly became a gathering place for artists when it opened shop on Broadway (it has since relocated to Hollywood Boulevard).

“Most of us were just one step above camping out. We had a roof over our heads, a toilet and running water and not much more, unless of course you count all the wonderful space,” recalls Peterson, now primarily a real estate developer whose recent projects include the 160-unit Little Tokyo Lofts complex, a few blocks southeast of his former starving-artist digs.

Gronk was among those artists who moved downtown to be close to this creatively chaotic scene. Drawing on those wild and woolly years, he produced two acclaimed series of paintings — “Hotel Senator: 23 Portals to the Underworld” (1990) and “Grand Hotel” (1989), whose namesake is only a few blocks from his current address. “It was not grand when I was living there, it was a bordello,” he says.

Gronk’s current home — a high-ceilinged, L-shaped, 2,500-square-foot loft at the roiling edge of the Fashion District — is constantly in flux, tapping the restless energy of the surrounding streets. Stepping into the lobby of the former bank building, you encounter one of his large canvases, an abstract study in black and white that suggests Arshile Gorky by way of Frank Stella. It’s on indefinite loan from the artist as a sort of housewarming gift to his fellow tenants, reflecting Gronk’s belief that his building’s most vital amenities are placed there by the residents themselves.

Uh-oh, looks like the elevator’s not working — again. Gronk takes this news literally in stride. “You didn’t know we had a StairMaster?” he jokes, heading up a flight of steps to his fourth-floor unit sequestered deep inside the building and reached via a series of winding passages, like a Minotaur’s lair. A long communal hallway covered from top to bottom with murals by Gronk creates a visual drumroll that reaches a crescendo at the artist’s front door.

Inside, practically everywhere you look, art stares back at you. A self-portrait resides on a far wall. The kitchen cabinets are inscribed with whimsical, Miró-esque shapes. Above the sink hangs an antique street sign for Brooklyn Avenue, the Boyle Heights thoroughfare that was a landmark of Gronk’s Eastside upbringing.

Even the bathroom is lined with posters, plastic action figures and other artifacts that recall Gronk’s student days as a politically impassioned Chicano artist-provocateur. Any found object or impression he gleans while out roaming the streets — the play of light and shadow on an Art Deco façade, a snatch of a street vendor’s jingle — may eventually find its way into his work or indirectly shape his loft’s decor.

Not surprisingly, given his theatrical flair, Gronk makes a point of knowing most of the dramatis personae in and around his building, which contains about 30 units. Only two other people lived there when he first moved in. Today, there are university students, a firefighter, a Cal State Northridge professor, an urban theorist. “I believe even a pig lives in the building — and I’m not referring to one of the tenants.”

When he’s home, Gronk usually leaves his door open to encourage neighbors to drop in and chat over a cup of strong coffee. “I’m Yoda here,” he says. “I’m the wise old person who lives in the building. I’m kind of like the person who has the salt and pepper, the spoons, the forks. I’m the adult that everybody comes to borrow from.” If the front door’s closed, his neighbors know he’s working and not to be disturbed.

When he needs a break from his labors or simply wants a change of scene, Gronk steps through a tall window between his kitchen and work space onto a garden patio that occupies the building’s upper-story courtyard. Not that he feels the need to escape his environs very often. He once tried Silver Lake for a year, but felt as if he were living in “Blue Velvet,” he says — all those strangers “smiling and waving and saying hello.” Give him Fellini over David Lynch any day.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.