Adrift in a dream’s dark side

- Share via

The low sunlight angling onto Howard Jones Field mimics in intensity the concentration of USC’s football players as they hustle through late-afternoon practice. Signal calls, hand-clapping and the bellowing of coaches reverberate against the high walls of nearby Lyon Recreation Center.

The scene would be intimately familiar to Travis Claridge, who once added his voice and muscle to the tableau.

FOR THE RECORD:

Travis Claridge: An article in Saturday’s Section A on former USC football player Travis Claridge erred in identifying Claridge’s hometown. It is Vancouver, Wash., not Fort Vancouver, Wash. The name of the high school Claridge attended is Fort Vancouver High School.

Claridge played four seasons for the Trojans, from 1996 through 1999. He was a starter from his freshman year on, a rare distinction, given the mental and physical demands of playing on the offensive line. “Has there ever been an 18-year-old offensive lineman this good?” The Times’ Earl Gustkey wondered when Claridge debuted. At 6 feet 6 and nearly 300 pounds, he became an All-American, and was the fourth offensive lineman taken in the 2000 National Football League draft.

The rituals of college football -- practice, halftime shows, antic fans -- lend the game an illusion of constancy. The heads beneath the helmets, however, know that for them it is ephemeral. Every player now on Howard Jones Field will be gone from USC in four, at most five, years, just as Claridge is gone. With luck, none of them will share his ultimate fate any time soon.

Claridge was born in Detroit and spent his early childhood in nearby Almont, Mich. His father, Bill, worked in quality control for Ford Motor Co. and was an assistant football coach at Almont High School.

Travis served as water boy for the Almont High team when he was a second-grader and wore a miniature varsity jacket.

When Bill and Travis’ mother, Denise, divorced, Bill went to work for Toyota in Torrance in 1986. Two years later, he and his ex-wife decided that Travis should join him and that his younger brother Ryan should remain in Michigan.

In 1991, Toyota transferred Bill to Fort Vancouver, Wash., and it was there that Travis’ football career was launched.

As an eighth-grader, Travis announced that he intended to play in the NFL and began striving single-mindedly for that goal. He started lifting weights daily, and Bill often joined him.

Bill saw his role as taskmaster in football and academics. He was aware that the family in Michigan, whom Travis visited regularly, thought that his task-mastering was an effort to fulfill his own aspirations through his son. Travis, however, had freely set a goal for himself, and Bill believed that it was his responsibility to “just make sure I gave him the right things for his toolbox.”

Travis played for the Fort Vancouver High School Trappers, and what he lacked in technique, he compensated for with strength. He was named a USA Today first-team All-American, designated a Parade Magazine All-American and pictured on the cover of the National College Recruiting Assn.’s magazine. He became one of the most highly rated high school offensive linemen in the country.

The first college coach to telephone him -- at 12:01 a.m. on the first day recruiters legally could contact high school seniors -- was Mike Barry, then USC’s offensive line coach. After a visit to USC, Travis was sold.

The Fort Vancouver Trappers played their home games at Kiggins Bowl, a tidy stadium with a roofed grandstand that is surrounded by a serration of high evergreens. After his final game there, Travis dug up a patch of the turf and asked Bill to plant it in his front lawn.

“I never want this to end,” he told his father. “You’ve got to plant this so when I come home I can touch the stuff that got me going.”

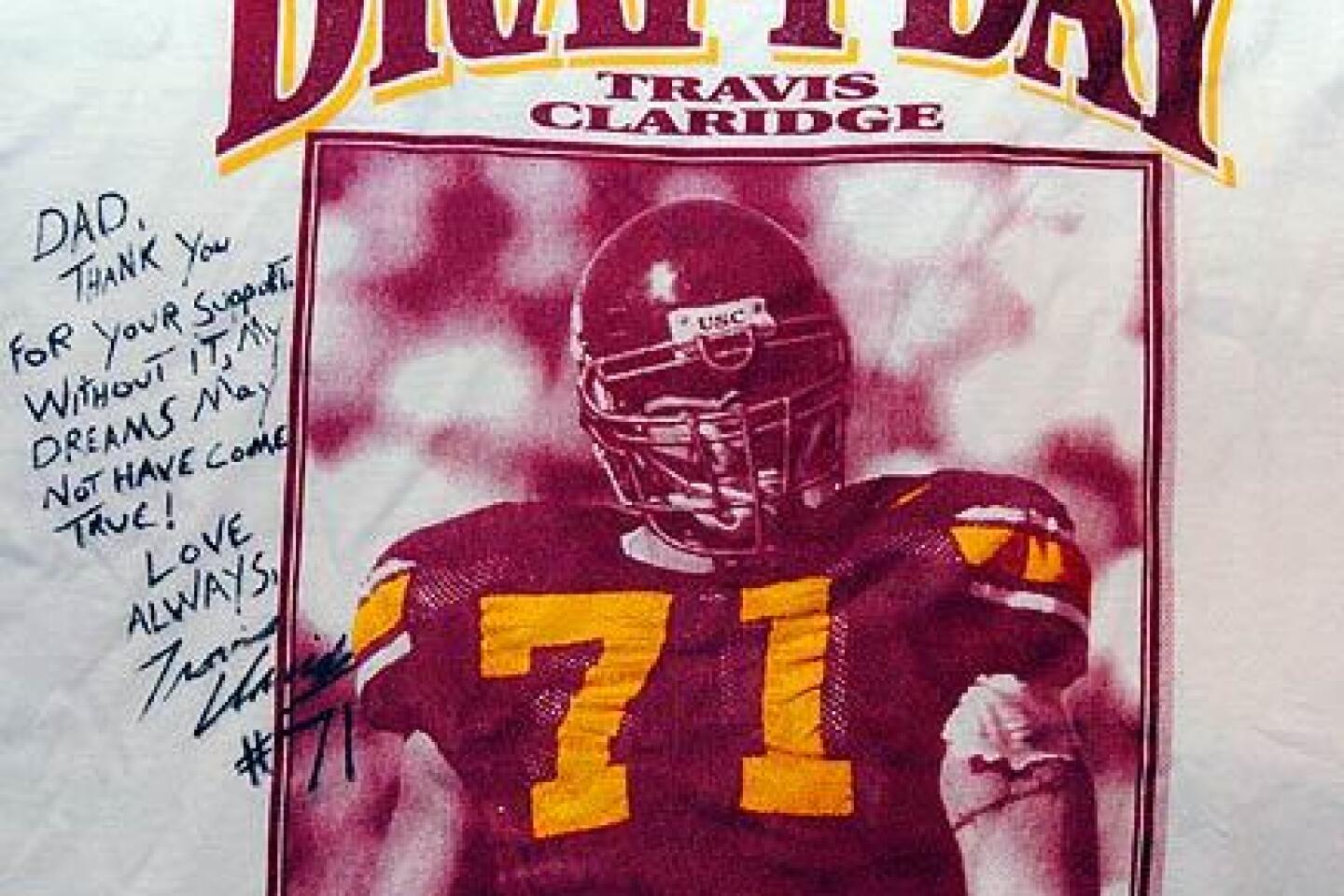

Travis was vain about his physique and never wanted to resemble the stereotypical barrel-bellied offensive lineman. He chose 71 as his uniform number because he thought it accentuated the “V” of his weight-trained torso.

A fan of the stagy melodramatists of the World Wrestling Federation, he imagined joining them when his football days were over. He already had a character he wanted to play: The Preacher, who would enter the ring clad in black, wearing a broad-brimmed hat and clutching a Bible.

When Steve Greatwood became USC offensive line coach in Travis’ junior year, he found the star lineman to be a loner, unusual among notoriously clannish O-linemen. The coach made it his business to integrate him with the others, and by the time Travis was a senior, he had developed an easy sociability, sitting among a group at the back of film-watching sessions, cracking wise in pro wrestler voices and emitting digestive sounds.

Travis let few people know him truly well, but to those few he revealed a core of sensitivity, compassion and uncertainty, as well as a tendency to be either buoyant or downcast. His high school girlfriend, Jennifer Johnston, believed that Travis inwardly grieved his parents’ divorce, as well as the absence of his mother and brother Ryan from his everyday life.

When Bill remarried, Travis served as best man -- via speakerphone from Los Angeles the day of a USC game. For a time, Travis had a turbulent relationship with his stepmother, Teresa. After she became pregnant, however, his attitude shifted.

Teresa gave birth to a girl, Riley, in March 1998, and Travis became her godfather. He doted on the baby, and pictures of Riley and her immense older half brother started to fill family scrapbooks.

The expansion of the family softened the dynamic between Travis and Bill.

Bill had always provided his son with an affluent life (a new pickup truck each year, for example), but sometimes, his rigors grated.

“My dad, he used to be pretty tough on me to motivate me,” Travis told a Times reporter his senior year at USC. “I don’t know if that’s the right way, but it worked. But, gosh, no. I wouldn’t do it to my son.”

After a road game against Oregon, a game Bill attended, Travis came to Greatwood’s office and broke into tears. “No matter what I do, it’s never enough to please my father,” he said.

No one who was familiar with them, however, doubted that a special bond connected Travis and Bill. Barry, who came to know both of them well, thought that although Bill’s methods sometimes shook Travis’ confidence, “that boy was the sun, the moon and the stars to his dad.”

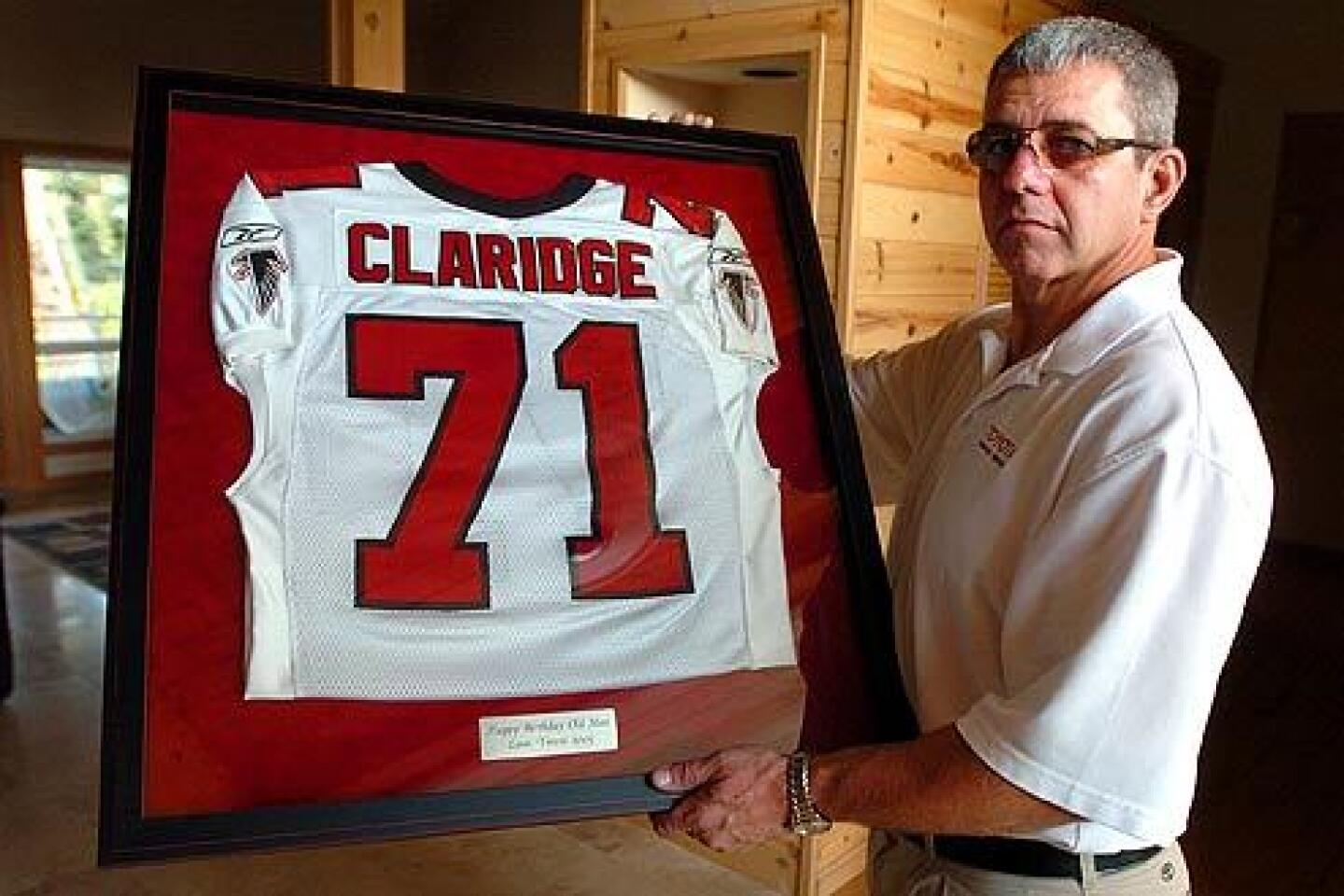

On the T-shirt Travis wore the day he was drafted by the Atlanta Falcons of the NFL, he wrote, “Dad, Thank you for your support. Without it, my dreams may not have come true. Love always.” On the No. 71 Falcons uniform jersey he wore the day Atlanta upset the Green Bay Packers in a playoff game in January 2003, he wrote above the “1,” “Dad, you have always been this number in my heart.”

As a Trojan, Travis fell into a long line of standout offensive linemen. The difference was that many of his predecessors played when USC, which had won five national titles since 1962, was an eminent power.

Travis, however, was a Trojan when the program was in eclipse. In fact, the Trojans’ offense dropped to the cellar of the Pac-10 conference in total yards rushing, a direct reflection of offensive line play. USC lost 22 games during Travis’ four years.

Every loss was anguishing for Travis. He was merciless on himself when he made mistakes, and unsettled by the thought that an opponent might be his equal or better. Such reverses flogged him to work harder in the weight room and on the practice field.

He had his shortcomings. He was “high cut” -- his V-shaped torso making him somewhat top-heavy. He was a devastating run blocker but had to work at pass blocking in a more upright position. At the big-time college level, brute strength alone didn’t always suffice.

Still, Travis’ achievements were exceptional. According to the professional sports information agency The Sports Xchange, he played in (and started) all 48 games as a Trojan, participating in 3,218 plays. He allowed a total of only 11 quarterback sacks, one in his senior year. He delivered 31 blocks that led to touchdowns (12 as a senior) and 332 “key” blocks or “pancakes,” the latter being instances when he knocked an opponent flat.

As a senior, he was named a second-team All-American by SportsPage.com and CBS Sportsline, and third-team All-American by The Sporting News. He was a unanimous choice for the All-Pac-10 conference first team and won the Morris Trophy, which is given annually to the conference’s best offensive lineman.

In 2000, he was drafted into the NFL, the 37th player overall to be taken, and the fourth offensive lineman. The Falcons signed him to a four-year contract worth $3.3 million.

The odds against a player making it to the NFL are overwhelming. According to the National Football League Players Assn., of the 100,000 high school seniors who play football in any year, only 215 -- 0.2% -- will ever see their names on an NFL roster. Moreover, the average career of a pro lasts only about 3 1/2 years.

Into this unpromising calculus entered Travis, his size and strength no longer unique, his opponents uniformly faster, more agile and, playing for large paychecks, more ferocious than even a big-time collegiate player was accustomed to.

The Atlanta Falcons had been to the Super Bowl after the 1998 season but won only five of 16 games the next year. Much of the blame was placed on the offensive line. The selection of Travis reflected the team’s determination to improve it.

Travis won a starting position in his rookie year, and his hard education in the pro game began in earnest.

He “struggled badly in pass protection” during a 41-20 loss to the St. Louis Rams, according to the Atlanta Journal Constitution. After a 38-10 rout by the Philadelphia Eagles, Travis told the paper, “I’m going to walk around Georgia with my head down so nobody knows who I am.” After a 16-6 loss to the San Francisco 49ers, Falcons head Coach Dan Reeves said the opponents’ defensive line “ravaged” Travis.

The Falcons finished the season 4-12. The offensive line had surrendered 61 sacks of Atlanta quarterbacks. During the campaign, Travis had played through a groin pull, a strained biceps and a sprained knee. In all he had played well enough, however, to receive the Falcons’ Rookie of the Year Award from Reeves.

Travis had mushroomed to 327 pounds during his rookie season but showed up at training camp the following year 28 pounds lighter. He started at right tackle -- a critical position responsible for protecting the non-throwing or “blind” side of heralded rookie quarterback Michael Vick, a left-hander.

The season did not go well. Travis, who was judged by the Atlanta paper as “not especially nimble,” was replaced as a starter late in the season. The paper said he had “disappeared” in terms of effectiveness. The Falcons went 7-9.

The 2002 season began inauspiciously. In training camp, Travis broke a bone in his right wrist and played with a cast the remainder of the year. But he more than held his own as a starting guard on a much improved line. It powered the Falcons to a league ranking of No. 4 in rushing offense and to 10 victories.

In the meantime, Travis’ injuries mounted. Knees, shoulders, arms and spine had all been compromised in the endless, close-quarter combat of offensive line play.

At practice in September, at the beginning of the 2003 season, Travis aggravated a strained shoulder, which turned out to be torn. Then in a “Monday Night Football” game against the St. Louis Rams, he tore tissue that connected his right thigh muscle to his knee.

Travis was placed on the injured reserve list and did not play again for the Falcons.

In 2004, Travis’ contract was up, and the Falcons did not re-sign him.

“I always played for the organization,” he later told a wire service reporter. “I broke my wrist, I played with that. I bruised my spinal cord, I played the next week. I got a concussion, I played through that. I . . . did so thinking when it came time [for a new contract] they’d say, ‘This is a guy who is a hard worker and is loyal to this organization,’ but obviously it didn’t work out that way.”

The Carolina Panthers thought he could still start and signed him to a two-year contract for $1.8 million, including a $500,000 signing bonus.

Training camp, however, did not go well. Panthers management found him insufficiently agile. To his astonishment, Travis was cut as camp ended.

He walked away with his $500,000 bonus, and a deeply wounded self-image. Barry, now coaching with the Detroit Lions of the NFL, encouraged him to ask other teams for a tryout.

None, however, was interested.

Being cut was “the most embarrassing thing to happen to me because I’ve never not started,” Travis told the wire service reporter. “All the people who were calling me when I was making big money . . . weren’t calling anymore. And when I hurt my knee, no one called except my brother, mom and dad, and two college buddies.”

Money was not a problem. Travis had been careful with his. He had rented a house in Las Vegas, where his brother Ryan, three years his junior, played linebacker for the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He was not one for luxuries.

Travis couldn’t abide life without football and in 2005, when the Hamilton Tiger Cats of the Canadian Football League offered him a one-year contract at $175,000, he leaped at it.

Travis took instantly to the Canadian game, its informality and the camaraderie of teammates who played for the love of football as much as anything else.

“I’m not making much money now, but I’m staying with some players,” Travis told the Canadian Press wire service in September 2005. “I’ve got a room. They got me a bigger futon because the one I had wasn’t big enough.”

As No. 57 for the Ti-Cats, Travis won the Canadian sports broadcasting company TSN’s “Friday Night Gladiator” award in his first game, against the Edmonton Eskimos. The prize was a Tissot watch. Travis gave it to Bill, who has worn it daily since.

During his second game, however, Travis’ right thigh muscle again parted company with the knee as he was backpedaling to pass-block against the now-moribund Ottawa Renegades, finishing him for the season. He returned to the states and started taking painkillers while rehabilitating his leg. By January 2006, he had bulked to 337 pounds, all of it looking like muscle, and Barry was trying to interest the Detroit Lions in giving him a look.

On Feb. 28, Bill was at work when he received a message to contact company security immediately.

On the phone was his ex-wife. She told him that Travis had been found dead that morning at his Las Vegas home.

Bill’s shock was compounded by the realization he would have to break the news to 7-year-old Riley.

“Your brother has passed away,” he finally told her.

“What do you mean?” she asked.

“Well, he died.”

There was a pause.

“We’ll just have to pray really hard for him,” she said.

Police had been summoned to Travis’ home by his girlfriend, Michelle Ashley, after she had been unable to rouse him. Ashley told detectives that Travis was addicted to painkillers. Police reported that they found anabolic steroids in the house.

A coroner’s investigator inventoried Travis’ medical history and listed leg injuries, adolescent asthma and bipolar disorder.

The autopsy performed by Clark County medical examiner Dr. Alane Olson found that Travis’ heart was extremely enlarged, which could have resulted from excessive physical exercise or steroid use or both.

Lab reports showed a “therapeutic” amount of the painkiller hydrocodone in Travis.

They also showed a potentially fatal amount of the powerful and highly addictive painkiller oxycodone, sold under the trade name OxyContin and reportedly commonplace in pro football locker rooms.

Olson knew, however, that a person accustomed to using the drug could build a resistance to the most damaging effects of the amount found in Travis.

Travis’ lungs seemed to provide the answer to his death. Numerous sections of lung tissue showed inflammation, a sign of acute pneumonia, which could be largely asymptomatic and fatal within days.

She concluded that pneumonia caused Travis’ death, and that an enlarged heart and oxycodone intoxication were “other significant factors.”

While the autopsy was being performed, Bill went to Travis’ house and found it in disarray after the police search. He cleaned Travis’ bedroom and washed his clothes, because he wanted the place “to have some dignity.”

Later, at the funeral home, he saw Travis, wrapped in plastic. The funeral director offered to remove the plastic and, with a clearer view, Bill thought that Travis “looked peaceful, like he didn’t have a worry. ‘Now I’m free.’ ”

Travis’ family from Michigan, his brother Ryan and Bill gathered for a viewing. After the others had left, Bill returned to the viewing room and for nearly two hours spoke privately to Travis.

Travis willed all of his assets to Ryan. His will named his mother as executor. His body was removed to Michigan for funeral and cremation.

Afterward, Bill picked up Travis’ white bulldog Goliath, a.k.a. Fat Buddy, and brought him home to Fort Vancouver.

Like Howard Jones Field, Kiggins Bowl, where Travis played high school football, often reverberates with the sounds of the game.

On a recent afternoon, however, it was empty and quiet as Bill Claridge walked its perimeter, conjuring memories, pondering whether there can be any sense to the death of a young loved one, or any comfort for it.

After his divorce from Travis’ mother, he had been married for a second time and had another son, named Daniel. When that boy was 18 months old, he and his mother moved to Denmark and Bill lost contact with them.

Five months after Travis’ death, his ex-wife from Denmark telephoned. She had just learned of Travis’ passing and offered condolences. She also told Bill that Daniel wanted to get to know him.

Bill last had seen Daniel when he put him on a plane to Denmark as a toddler. He next saw him disembark from a plane a 17-year-old. Daniel was 5 feet 8, a miniature version of his father.

“If you saw him on a football field, you’d assume he was the placekicker,” Bill said. Daniel, bright and easygoing, stayed with Bill, Teresa and Riley for two weeks. Riley was delighted to find she had an extra brother.

Some things have changed at Kiggins Bowl since Travis’ day. The playing field now has an artificial surface.

The patch of natural turf Travis had given Bill to plant in his lawn after that final high school game, however, took root. “Whenever he got out of his truck, he’d stomp on it for good luck,” Bill recalled.

Thanks to Travis’ watering and fertilizing, the patch has infiltrated Bill’s entire yard and is indistinguishable from the grass that was there before.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.