Search for missing L.A. girl ends at hospital bedside

- Share via

Diana Tomas was found clinging to life with a gunshot wound in her head on a pathway alongside the 101 Freeway not far from downtown Los Angeles, the possible victim of a stray bullet.

But for four agonizing days, her mother tried to locate the 14-year-old girl, reaching her hospital bedside only a short time before she died.

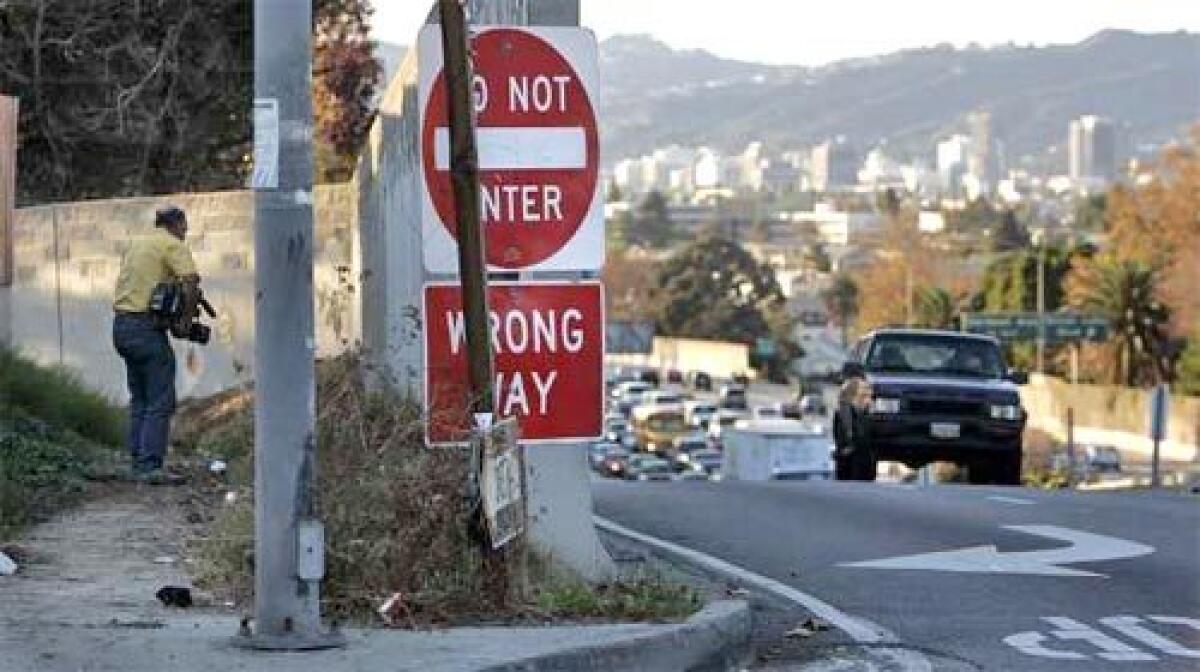

The teenager was on a narrow pathway that runs along the freeway sound wall near the Benton Way exit, out of view of the street, on the afternoon of Dec. 2, when a bullet fired from somewhere nearby struck her. A passerby heard the gunshot and found her. She was taken to County-USC Medical Center

That same afternoon, Diana’s mother had gone to the Rampart police station to report her missing. Diana was a Virgil Middle School student who sometimes ran away from home.

Officers took the report, not realizing that she was the same person then lingering on a respirator at the hospital. Detectives thought that their victim was a young woman of about 22 and listed her as a “Jane Doe.” And Diana had never been arrested, so when she was fingerprinted at the hospital, police could find no match.

LAPD officers routinely check hospitals and the Los Angeles County coroner’s office after receiving a missing-person report. But they did not match Diana’s record with the report of an older Jane Doe.

“She appeared older,” said Lt. Joe Losorelli of the Los Angeles Police Department’s Rampart station. “She had a tattoo on her upper body, and most 14-year-olds don’t have one. Most tattoo places won’t put a tattoo on a child.”

It took a few more days to piece everything together. Diana’s mother heard a rumor in her neighborhood that a young woman had been shot. She returned to the station to ask if the woman might be her daughter.

A detective who was on duty that night drove the mother to the hospital for what Losorelli described as a sad and uncomfortable scene: The mother saw her daughter briefly -- on life support at that point -- and identified her. Diana died Dec. 6.

The episode, although harrowing, is not unique. In a county where about 1,000 people die annually in homicides, mostly shootings, many victims are not immediately identified, especially if they carry no personal documentation, or if they have never been arrested and therefore lack fingerprint records.

In some cases, police and coroner’s investigators can spend months trying to track down family members without success.

The task is made more difficult because Los Angeles has many immigrants whose records remain in other countries, and whose names are either very common, anglicized or simply mangled. And there are so many missing persons reported to police that mismatches sometimes occur.

Last year, the unclaimed remains of 879 people were transferred to the Los Angeles County morgue to be held for a year before anonymous burial.

Diana fit the profile of those seemingly forgotten victims in other ways. One of Diana’s childhood friends said she had heard that the girl was missing. She said Diana often had problems with her mother and had run away in the past.

The friend, a youngster with a pierced tongue, was speechless when told Tuesday that Diana had died from a gunshot a few days earlier. She stood fidgeting with her necklace for a long moment, looking puzzled as friends tugged her arm, trying to pull her away.

Other school friends said that Diana spent more time outside school than in, passing time in the neighborhood and eating tacos at a restaurant.

Arturo Valdez, Virgil Middle School assistant principal, said the girl recently had some trouble and had stopped attending school on a regular basis. The mother sought help from the school. Recently “we saw mom more than we did the girl,” Valdez said.

But Diana also was a “vibrant, happy young lady” who loved to write, said Rampart homicide Det. Julian Pere, quoting family members. Her companions may have steered her astray, he said.

“She probably befriended the wrong people,” Pere said.

Although Diana’s age and gender made her death exceptional, hers was by no means the only teenage killing. Homicides are at a low point in Rampart Division this year, as they are in most areas of the county. Yet in this precinct surrounding MacArthur Park two 14-year-old boys, Rene Vargas and Erwin Escobar, were killed, as was 17-year-old Abigail Sarai Lopez and 16-year-old Joel Martinez. He was found shot on Easter Sunday not far from where Diana died.

Two other girls, 16-year-old Nelli Rodriguez and 15-year-old Connie Williams, were killed by gunfire earlier this year in LAPD’s Newton Division, southeast of the Rampart Division.

It also is not uncommon for death from violence to come slowly. Many victims die days, weeks, years or, in rare cases, decades after being assaulted. In a few cases this year, people who suffered relatively minor beating injuries were sent home from the hospital but later developed infections or other complications and died.

Two days before Diana’s death, Alan Mendez, 18, died eight days after he had been shot in Inglewood.

Most homicide victims, however, are adults. Det. Fred Faustino said investigators had no idea that Diana was a child until her mother made her emotionally charged identification.

“It was shocking to us when we found out she was 14,” Faustino said.

Detectives are seeking information on the case. They are at (213) 207-2060.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.